- Start

- The impact of the HIV/ AIDS pandemic on queer spatial production

- What are queer spaces and how can they be mapped?

- How have Aachen’s queer spaces overcome crises and bloomed despite/ during them?

- Klappen: first informal queering of public spaces

- Bars: first organized queer safe spaces

- Associations: solidarity-bloom during 1990s HIV crisis

- Events and parties: a reaction to the economic crisis of 2008

- Queer Cyberspace: arises in 21st century, becomes indispensable in crisis

- How do digital spaces impact (physical-, queer-) spatial production?

- A need for digital transition

- Impact of digital transition on queer communities and spaces

- Conclusion: Queer(ing digital) citymaking

- About the author(s)

- References

Published 15.11.2021

Queer(ing Digital) Citymaking

Resilience Through Local and Virtual Queer Spatial Production in Times of Crisis

Keywords: Queer spaces; cyberspace; community empowerment; resilience; crisis; safe spaces

Abstract:

Social, economic, and political crises have always affected minorities disproportionately. Nevertheless, these times also offer a potential for the creation and reinvention of communities to support each other through safe spaces. This article explores the ways in which queer/ LGBTQ+ citizens deal with spatial production in times of need, through case studies both locally in Aachen and in global digital contexts. Queer communities have had to improvise and develop alternative urban strategies, reimagining mainstream processes of spatial production and offering support to each other against discrimination and insecurity. How have they been able to remain resilient and in which ways have they questioned and reinterpreted Architecture and Urbanism in the process? What is the impact of new contexts such as digital queer spaces on physical spatial production? This article is based upon the findings of the master’s thesis QUEERingAACHEN. State of the art and potential of queer spaces in Aachen.

The impact of the HIV/ AIDS pandemic on queer spatial production

The year 2020 has meant a global social and digital reset in many ways: the threats of a deadly pandemic, the difficulty to feel welcomed outside in society, a need for safety and therefore safe spaces, etc. Global health crises are nevertheless not new and have several recent precedents, one of which – the HIV crisis – had a notable social and spatial impact in the late 1980s and 1990s, especially within gay/ queer communities. Being seen as an isolated gay sickness at first and because of a lack of understanding of it, the media coverage and politics around the HIV-virus at that time has been described as „a testament to the pervasive cultural prejudices of the time“ as well as an „editorial neglect“ (Rosenzweig 2018). This stigmatization had an impact on the research and treatment of the virus, as “language about different illnesses and the political and medical response to them are inextricably entwined” (Sontag 1989). This way, a generation of mostly queer men was slowly dying without answers and found the need to take initative, organize, and help each other, i.e. became volunteers, social workers or medical professionals. An example of this is Dr. med. Heribert Knechten, who founded his own medical practice in the town of Aachen (Germany) in 1992, in order to “become a doctor for the gays” after realizing the lack of information and resources on the pandemic, even within the medical community (Sánchez-Molero 2020b: 47).

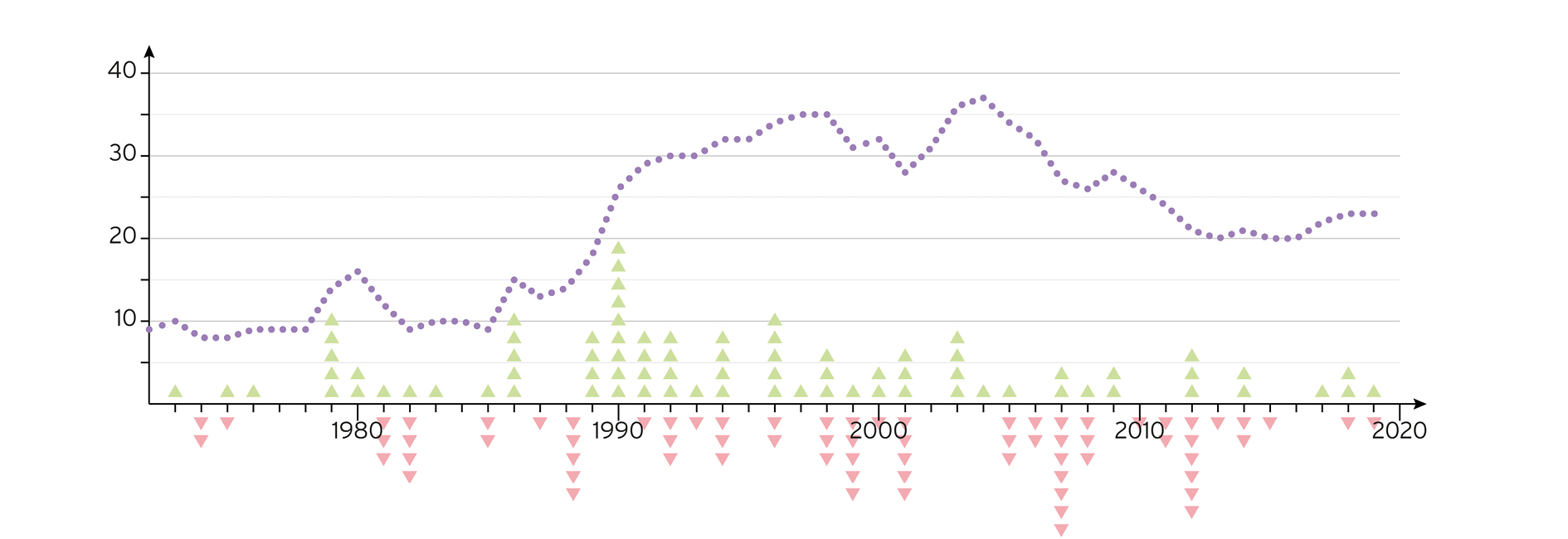

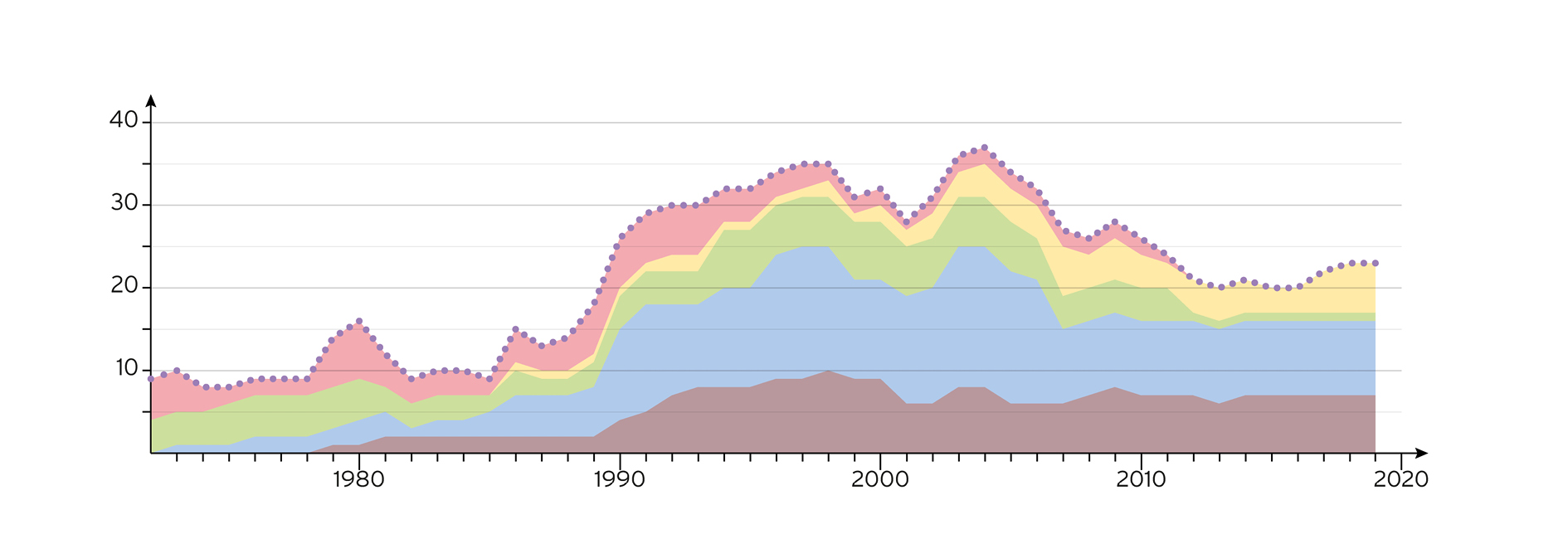

The gay community reacted in horror as the virus reached the town but quickly started e.g. organizing donations for patients, opening offices and support groups, i.e. a range of spatial supplies that had to be created because of the local and federal governments’ lack of engagement. With an enforced taboo and mistrust for the gay population came a marginalization and an unequal access to – and safety in – the public space. The implications of HIV patients’ isolation and the deathly rate of the virus’ spreading provoked a rise in the creation of spaces and the establishment of associations in the beginning of the 1990s, in which LGBTQ+ inhabitants of both metropolises and smaller cities in Germany started organizing to educate, share experiences and show solidarity to each other. In the case of Aachen, the amount of such safe spaces doubled from less than 10 in the mid-1980s to over 30 queer spaces in the mid-1990s.

What are queer spaces and how can they be mapped?

Case study Aachen. Societies and municipalities are in constant transformation; in the same way, queer spaces have changed throughout time, and citizens have found new ways to co-create them. Using Aachen as a case study and exploring its queer spaces, there is a notable evolution during the past half-century. In order to describe these spatial productions, the following definition breaks down their elementary characteristics.Although queer spaces vary in scale, outreach, location, design, etcetera, they share essential attributes that queer them: their functions, constitutions, social actors and uses (Sánchez-Molero 2020a: 14).

Function: The main goal is to establish safe spaces, a protection against homo- and transphobic oppression for people who fall under the diverse umbrella-term of queer (Anzaldúa 1991). Queer experiences and identities within the spectrums of gender and sexuality (Killermann 2020) reject strict heteronormativity (i.e., the social norm of having to be a straight man/ woman) and may diverge from the gender binary. These ideas of spectrality are also applied to the spatial dimension, breaking down the sociological understanding of space: In the same way that space can be represented through different dimensions, queer spaces also offer, in addition to the material dimension, social, political, and symbolic values (Gestring et al. 2002).

Constitution: The process in which queer spaces are built is not purely physical/ material – the social construction or queering of spaces through action or visibility, e.g. a demonstration such as a Pride parade, offers an alternative use, repurposing, reclaiming, and appropriation of a public space otherwise mainstream or even hostile towards social minorities.

Social actors: Queer citizens are responsible for queer spaces, but they also take on the roles of (co-)founders and/ or helpers in the creation of these heterotopias, or are simply visitors in them (eventually alongside LGBTQ+ allies).

Uses: Often, a single space will host several uses, either at the same time or throughout a certain period. Especially associations and social clubs with a set program cater towards a whole range of visitor groups and activities.

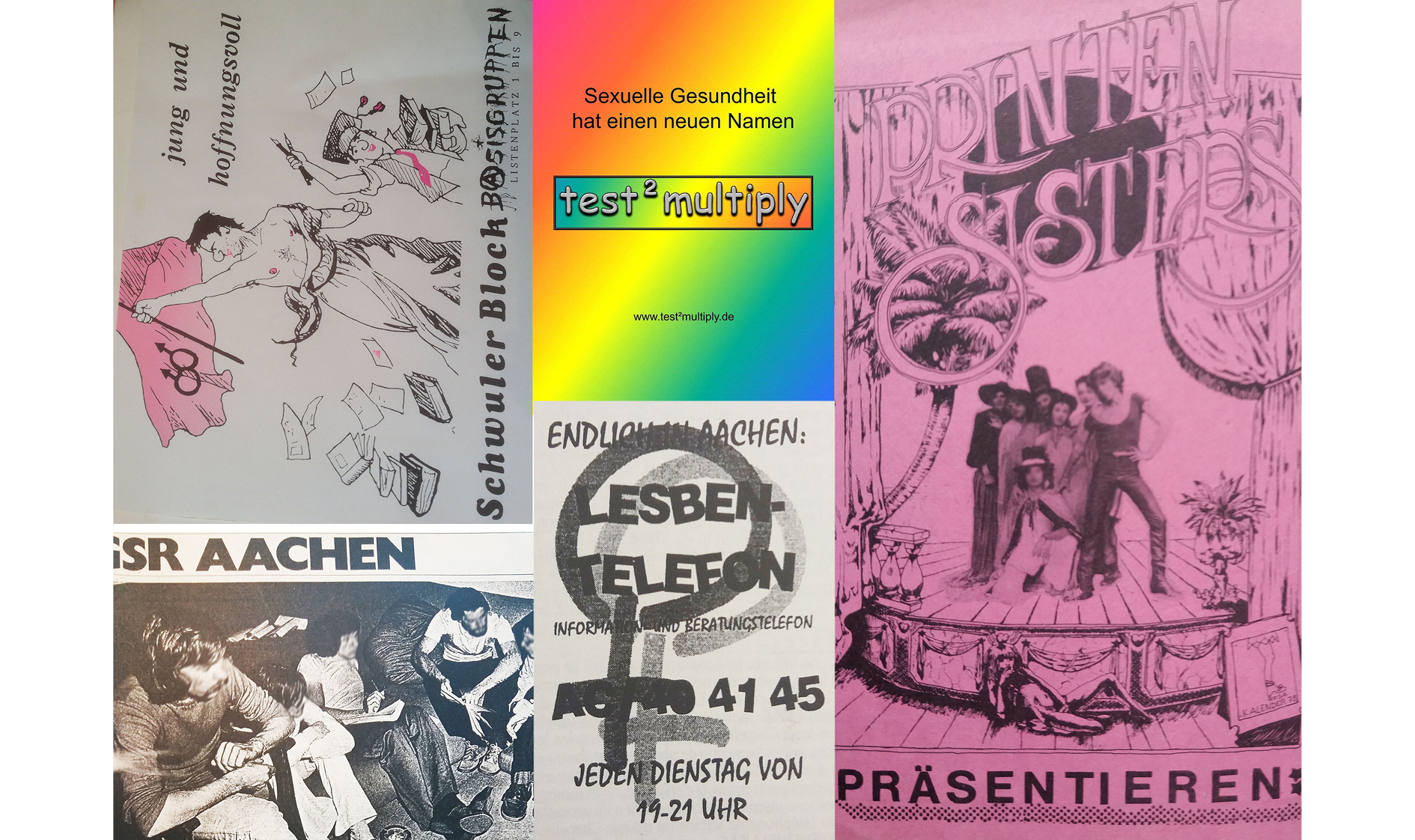

The search for information and literature on queer spaces in Aachen proves a lack of research from local authorities, official statistics, and media coverage ‚outside‘ the LGBTQIA+ community. It is thanks to word-of-mouth stories from witnesses, physical evidence, and historical materials that one can find traces of queer communities and spaces in Aachen. The archival work for the master’s Thesis QUEERingAACHEN looked into grass-root events, publications and prints to collect data for the mapping of queer spaces, using both analog historic materials such as magazines, posters, flyers and underground publications, as well as digital documentation, e.g. websites, social media, but also archives for closed-down blogs and webs. It becomes clear when examining these sources that queer actors have not merely created queer spaces but have also taken care of collecting historic materials, publications, and networks, which are essential for research. Centers such as the Schwules Museum Berlin or the Centrum für Schwule Geschichte in Cologne provide queer history and know-how shared publicly, often donated to by private archives or collections from associations and individuals.

This quantitative research of QUEERingAACHEN was accompanied by 14 interviews with several generations of queer (co-)founders, helpers, and visitors (activists, organizers, students, neighbors, and customers) of the found spaces, who provided their own facts about the dynamics of these spaces throughout the last 50 years. Contrasting the found data and evaluating the input from living witnesses resulted in a digital mapping of queer Aachen.

How have Aachen’s queer spaces overcome crises and bloomed despite/ during them?

Aachen, a city of around 250.000 inhabitants located in the tripoint of the Belgian, Dutch, and German borders has evolved from an Ancient Roman thermal settlement, Charlemagne’s residence, and a catholic pilgrimage destination into the contemporary technical university town it is today. During the last 50 years, the following kinds of spatial productions have emerged as a direct reaction to an evolutional shift in the needs of the queer population – additionally impacted by major events and crises: e.g. the outbreak of HIV in the late 1980s, the expansion of the internet, the economic crisis in 2008 and the Covid-19 pandemic.

Klappen: first informal queering of public spaces

Cruising, or the act of searching for informal, improvised, secret and incognito meetings for men who seek sexual intercourse with other men, is a well-known and researched practice that generally takes place in public spaces at late hours of the night. Early references of these spots can be found on gay guides (e.g. Spartacus International Gay Guide, von hinten Zeitschrift, etc.) but every major European city has evidence of the existence of such spaces and behaviors that date back centuries.

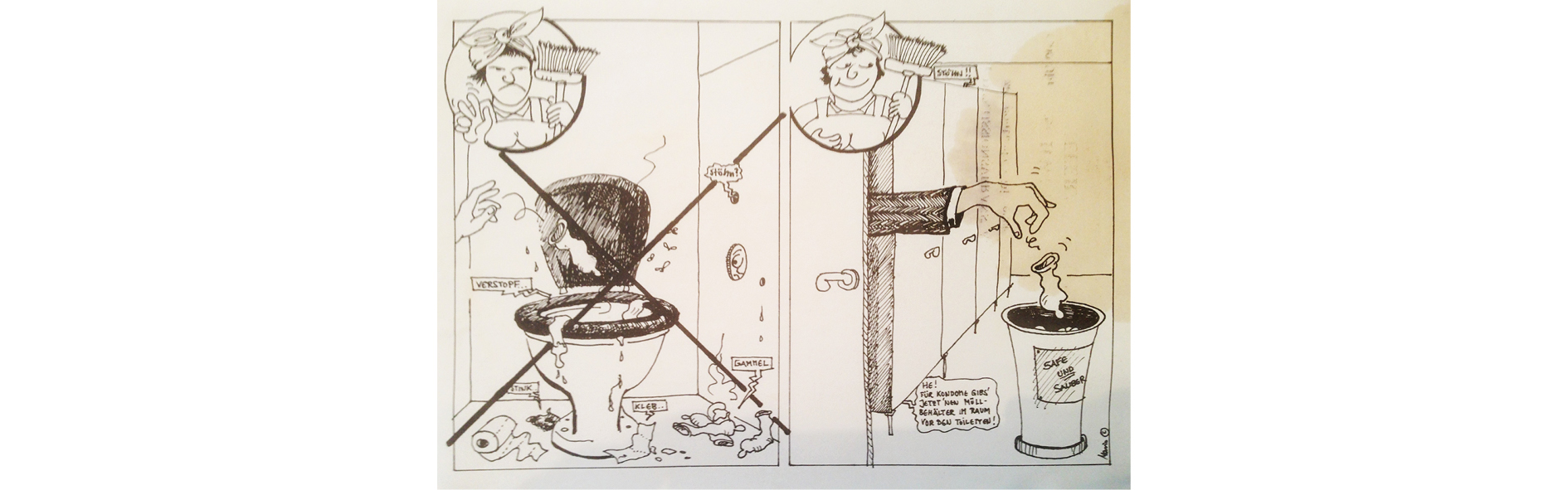

The German gay scene created its own vocabulary to refer to them: Klappen, probably the very first kinds of an ac-tive spatial queering in Aachen, generally public toilets for men which are known for being hosts to anonymous dates and sex. The way in which these practices are established, and these spaces socially constructed, is informal, unplanned, and emerge out of a need to live out one’s sexuality, which was not only taboo but also persecuted by German police well into the 1960s and 1970s. Taking advantage of the closing time of bars around midnight, and the reduced lighting of the empty streets, a network of cruising opportunities in toilets, parks, parking lots and corners arose around the city center and service stations on the side of the highway. The knowledge transfer about Klappen was similarly informal, hear-say, rumored, but, as some witnesses explain, „you would hear about it, you simply knew”.

Bars: first organized queer safe spaces

Queer bars became the first organized queer spaces in Aachen, mainly for gay men, being the main (co-)founders, helpers and visitors in them. While lesbian bars remained a minority in Aachen, certain clues indicate that queer women, as well as certain social and feminist groups, met either privately or in some already established bars they considered safe. This unequal (access to) spatial production can be explained considering that social oppressions or so-called components of vertical inequality (Kreckel 1992), such as misogyny and racism, are also internalized and reproduced through the social construction of space (Harvey 1989).

The goal of a queer bar was providing a safe space as a reaction to and protection from homophobic attacks and police raids. The 1960s and 1970s are decades remembered as still unsafe for queer visitors of these establishments, who had to knock on locked doors to access them. Often peepholes were installed in the entrance doors, as well as wooden planks on windows, which attempted to hide the bar’s existence. From the 1990s till the mid-2000s a shift in the visibility and presence towards the street brought the uncovering of windows and entrances, opening up the queer bars to the street and thus, Aachen’s mainstream passers-by (Sánchez-Molero 2020a).

Coming from an isolated small series of individual bars, this shift also brought the creation of networks between queer bars, and a “very lively scene” “made for and by us, the gay bar almost felt like a second living room”, as some citizens explain (Sánchez-Molero 2021). Hubs of queer bars started forming during several decades, this was often the case in Promenadenstraße, in which bars like Blockhaus, Gentleman, Club Gigolo and Placebo co-existed in the late 1980s/early 1990s (Figure 3). After a peak in the presence of queer bars in Aachen in the 1990s, all of them gradually disappeared, and finally in 2011 the last gay bar closed, being replaced by mainstream venues.

Associations: solidarity-bloom during 1990s HIV crisis

The origins of societies and associations were small advocacy groups of friends and acquaintances who met in bars, private apartments, or student accommodation, e.g. women’s rights and lesbian activists, two scenes who were often intertwined in the late 20th century. Having a space to meet and work regularly became essential so that groups of organized queer citizens could find associations to support each other. This was catalyzed by the turn of the decade into the 1990s, specifically through the spread of HIV, which had a direct impact on this specific spatial production, highlighting the need to shift from regular meetings (of informal character) to actual offices. Improvised initiatives turned into volunteering opportunities and social work, and thus Germany-wide networks such as Aidshilfe offered support to HIV patients, their families, and friends.

The unknown virus was affecting gay men disproportionately and a wide range of queer associations in Aachen provided with the following services and took on specific roles: information and data exchange on the pandemic, co-education around treatment and medical news, solidarity towards HIV patients such as fundraising – ultimately the alternative support system not provided by local and federal authorities or the mainstream. Such associations were organized by citizens pertaining to a variety of age groups, backgrounds, gender and sexualities, in which different ranges of cultural, social and political exchange was also focus points, often and still today planned in a regular program, e.g. sharing literature, films, and interests, socializing with like-minded people, exchanging ideas on political engagement and activism, organizing protests and campaigns, etcetera.

In addition to the physical spaces and the agendas, certain elements complemented the work of Aachen’s queer associations, e.g., telephone numbers to seek counseling and helplines against homophobia. Flyers also became widespread to advertise for campaigns, parties, meetings, … which were often also shared in independently published calendars along with literature and essays, such as those written by the Printen Sisters in the 1980s. Rosa Monat (Pink Month) was one of Aachen’s queer calendars, founded in 1992 as a physical copy and shared for free in queer spaces around the city (Figure 5). In 2000 it moved online and has been updated regularly ever since. In its almost 30 years of history, it has advertised and supported queer live activities and venues.

Events and parties: a reaction to the economic crisis of 2008

Queer temporary events have the opportunity to be independent from individual spaces, as they are easier to organize anywhere and to finance than a full-time bar. The amount of monthly/ biannual/ regular queer parties started gradually growing in the 1990s, parallel to the closing of queer venues, especially after the global economic recession of 2008 (see Figure 4). “It is difficult to organize queer parties but they are much needed!“ (Sánchez-Molero 2020b, 44). The goal was, of course, to party and socialize – but the origins of events, often run by students, such as Schwules Fest (Gay Party, which took place biannually for more than two decades, Figure 6) was to raise funds for queer associations and initiatives. “The event was in a huge hall in a hideous building, the bar was a plank on top of beer cases, (…) but the party was always wild“ (ibid.).

Other queer events include demonstrations and celebrations such as the IDaHoBiT* (International Day against Homophobia, Biphobia and Transphobia) and Pride parades/ CSDs (Christopher Street Day), during which groups of queer citizens take the streets and occupy central parts of Aachen temporarily, in the presence of symbols such as rainbow flags, and take the opportunity of holding the mainstream’s attention to prove “we are also here” and “we aren’t only a few” (ibid.). The meaning of both celebratory and demonstrational actions was the temporary queering of mainstream spaces, reclaiming, appropriating, and taking back spaces often unfriendly to the LGBTQ+ community.

Queer Cyberspace: arises in 21st century, becomes indispensable in crisis

Early transitions of queer spaces into virtual dimensions can be foreseen in the evolution of printed media, calendars, telephone numbers, but also the networking and contact of Aachen’s spaces and initiatives with outside organizations from other German and international cities. Almost simultaneously with the turn of the century, the growth of spatial creation stopped, and the online presence of queer spaces becomes more common, thus migrating some activities to the digital realm. This transition to Cyberspace (Dodge et al. 2001) shines a light on societal change and the development of different queer and spatial needs – a transformation of queer Aachen gradually took place after the realization of the possibility to reach out to queer populations through websites and later social media presence as the internet expanded and became essential in professional and private settings. A few examples include:

- Parties and events opened their own websites in the early 2000s, where they updated the newest dates and locations and uploaded party photographs.

- Associations created social media profiles to stay in touch with their users.

- Dating sites and apps became a new public space to meet others also looking for dates, friendship, or sex.

- Private and public groups are created on platforms such as Slack, Discord, Facebook, etc. to replace the closed down spaces during Covid-lockdowns.

Digital queer spaces are equally criticized and praised by the queer population of Aachen during interviews; often older generations blame them for the closing of physical spaces, while younger generations seek an opportunity to find their online community independently from geography (Sánchez-Molero 2020a), but understanding the history of Aachen’s queer scene proves its ever-evolving nature. A gradual but constant and innovative development of Aachen’s queer spaces has been highlighted by several crises: by a societal shift in opinions and treatment of the queer community, a digital expansion and transition, the competition with metropolises nearby, the increasing financial challenge to open and keep spaces afloat, especially in nightlife.

Most cities across Europe face similar challenges (Campkin and Marshall 2017 prove this in London, too). Prioritizing their own needs, providing for their own, understanding potentials and risks to reinvent or die, queer actors have developed their own strategy: Crises present challenges but not only as obstacles, they can be utilized as catalysts of the production of queer infrastructure. First services, programs, and activities that transcended physical spatial dimension in the 1990s hinted at a later abstraction into Cyberspace. The visual digital graphic presence of queer spaces merged from physically hidden taboos only known from within the community to a widespread online outreach, advertisement, and networking.

Aachen is a clear example of how local communities empower themselves on their own, often as guerrilla movements parallel to official processes, outside of social mainstream, and, in this case, not even being a (queer) metropolis such as Cologne, one of Germany’s queer hubs, 50 minutes by train from Aachen and for decades the main setting for queer scenes in West-Germany.

The digital transition of queer spaces in German and European cities has thus been foreseeable for several decades, since it has happened gradually through different dimensions, diversifying their presence and outreach, and partaking in the transformation of queer scenes. In this regard…

How do digital spaces impact (physical-, queer-) spatial production?

While the German/ European mainstream still struggles figuring out if the Munich football stadium should be wrapped in an outdated version of the rainbow flag (Babayiğit 2021), queer people have been busy finding ways to network and support each other on their own during Covid-lockdowns:

Aachen’s Queerreferat an den Aachener Hochschulen e.V. has existed since 1985 as one of North Rhine-Westphalia’s first queer student-lead societies. Their weekly program spans over a variety of functions and uses such as their café, meetings, plenary sessions, queer library, advice center, support hotline, coming-out groups, biannual celebrations, parties, demonstrations, readings, lectures, etcetera. The first lockdowns in March 2020 meant a sudden break in their plans but also a quick transition into digital hangouts in their own Discord server, in which several topics/ themes structure the chats, video-chats and posts of both organizers and visitors. For their 35th anniversary, they prepared a series of online presentations and meetings via Zoom for former helpers and for an open audience.

Digital tools (such as Zoom, Wonder, Gathertown, etc.) have become important, not only for academic and professional meetings, but also along with social media platforms (e.g. Instagram, Twitter, Facebook) as hosts for queer events: Parties, voguing classes, balls, kikis, … the lockdowns and quarantines have not stopped these events from happening, in an online setting.

In an international context, The Quarantine Online Function is an example of resourcefulness as a translation of a physical space into a digital setting. Ballroom communities have organized balls, events originally by and for queer QTBIPoC actors (Queer, Transgender, Black, Indigenous, People of Color) citizens of New York City in the second half of the 20th century. They are a celebration of performance, dance, and fashion, often otherwise not accessible to people outside of the mainstream heteronormativity; nowadays, global houses compete and celebrate each other in international competitions around the world.

Being an experienced Ballroom participant for several years, Diesel Meraki, based in Norway, decided to MC and put together The Quarantine Online Function on the 19th of March 2020 (Figure 7, left). In this semi-improvised event on Zoom, with a strong Italian presence on the judges’ table (in solidarity with the high number of Covid cases in that country at that time) several dozens of performers participated and over 500 people watched in the digital audience: “I had no idea that so many people wanted to watch and participate” – Diesel explains how the event was “very self-made” – “I had my laptop with Zoom up […] with the participants, the judges and DJ. While doing this, I had my phone on a tripod and livestreamed the screen through my Instagram live”. The aim was to “try creating a way for Ballroom people to meet online”, “and it worked”, as the event received an overwhelmingly joyful and positive feedback.

Pride for Sarah Hegazy, a demonstration and memorial held on June 12th 2021 at Wiener Platz in Cologne, Germany, was constituted digitally through a network of queer individuals and NGOs to honor the memory of Sarah Hegazy and keep her resistance alive, one year after the death of the queer and political activist from Egypt who took refuge in Canada (Figure 7, right). Organizers Ahmad Alhoe and Taim Nassr explain the planning and implementation of the digital and physical event: Going into a public space was essential for them in order to meet queer immigrants and refugees from the SWANA diaspora and remember Sarah. Unlike queers ‚back home‘ in countries where being out of the closet might mean a death sentence, going public was a possibility in Cologne to share the closeness of Sarah’s story to ours. Choosing Wiener Platz was not a coincidence either; to the wide presence of migrant neighbors and workers, the organizers comment: „it‘s important that they see us“.

On the digital dimension, graphics were posted on a social media profile and shared throughout networks of queer citizens of a similar age, who might be willing to participate. Targeting Generation Z and Millenial queers’ social media became a tool for quick dissemination instead of long texts and publications: simple and direct‘ for a short attention span, as they were influenced by actions by other queer initiatives and were also reposted by them within queer and Arab communities, reaching thousands in little time.

With limited but effective means, the digital advertising and spreading of the event did not need monetary support, and as for the banner printed for the event, it was financed by collaborating associations. This eased the process of the temporary queering of Wiener Platz, as well as the digital space since the event was livestreamed on Youtube and Facebook for those who couldn’t attend due to Covid restrictions or for others living abroad – under the motto neither forgive nor forget, Sarah’s struggle and activism was the essence of the event.

A need for digital transition

The possibilities of creating digital spaces and using online platforms throughout the pandemic means a possibility to adapt and keep working, networking, communicating, etc. This has translated not only into the need of home-officing for working citizens, but also for queer communities to turn to digital home-spacemaking/ home-citymaking. This kind of digital citymaking relies heavily on community-making, as space is socially constructed and communities are in need of safe spaces – whatever that spatiality/ scale/ dimension might be, and despite, or rather, because of social crises such as Covid-lockdowns. Being a minority in the city, queer communities seek networks from within and outside of the city (e.g. learning from other cities), building interregional or even international networks of associations to exchange urban know-how – i.e. act locally, think globally – and participate in global digital platforms.

Impact of digital transition on queer communities and spaces

Social media and digital spaces allow the creation of spaces in one’s own terms, being accessible globally, unlike the unequal experiences in physical space – e.g., the discrimination and violence suffered by Trans* citizens in the streets and public transport. Communities can often act more freely online than in physical spaces and be inspired by global communities otherwise far away from each other. Digital queer spaces reclaim, reinterpret, and create, the same way queer physical spaces do, but potentially with easier access and wider outreach.

At the same time, new ways of interacting eliminate/ reduce the need for certain spatial productions, as in Aachen’s queer bars case, a queer spatial production that doesn’t exist anymore. The opportunity to communicate with high speed and efficacy also undermines the need for physical visibility and socialization: Queer friends/ groups might delegate queer spatiality to the private space, setting up plans online and meeting in spaces they know are safe. Out of the closet and into the streets was a slogan used in queer demonstrations of the 1980s to call for action (D’Erasmo 1999) – some queer citizens see a danger in the historical development of queer presence in the city, worrying if performative activism and the comfort of new technologies have tamed the community (Sánchez-Molero 2020b: 46).

Conclusion: Queer(ing digital) citymaking

Urban and Architectural design has a direct effect on the everyday life of humans through unequal social power dynamics (Cosgrave 2019). A lack of consideration of minorities provokes unequal access to space and safety in the city: this is the origin of the need for safe queer spaces, both inside and outside of the metropolis. Dr. Petra L. Doan applies John Stuart Mill’s concept of the tyranny of the majority in the need for academic research on queer minorities and spaces, not for the sake of understanding individual places, but to understand their relation and access to the urban space – with the goal to shape the disciplines of Architecture and Urban Planning (Doan 2015).

By observing and understanding queer spatial functions, constitutions, social actors and uses, as well as their (co-)founders, helpers, and visitors, we can learn how cities can be co-created and can become more accessible to specific minorities, and to everyone. Queer spaces question the status quo of Architecture and Urbanism and participate in citymaking through queer urban performativity, to becoming resilient pioneers in times of crisis. They transcend materiality by questioning existing structures and providing multidimensional grass-root solutions.

More than 90 queer spaces have been active in Aachen’s past 50 years, as proven by the seemingly hidden data and knowledge carefully curated by queer communities. Most of them had closed by 2020, before the Covid-19 pandemic arrived in Germany, as is the case of most cities in Europe, in which an inability to keep queer venues afloat coincides with a rise of homophobic and especially transphobic and racist violence, having even lawmakers and governments defining LGBT-ideology free zones in Poland and LGBTIQ content banning laws in Hungary (European Commission 2021).

While virtual spaces have an increasingly pivotal role in community-making, they are neither a next/ final step of queer spatial production, nor a wish to replace physical space. Queer communities have recognized the impact of digital transition for decades and are willing to risk and implement it in their own agendas to profit from it. The same way in which spatial queering reinterprets material dimensions, queer spaces in the 2020s move and operate in a spectrum towards Cyberspace, by imitating behaviors and dynamics known in physical spaces, from which individuals profit and communities are empowered from. Instead of exclusively committing/ restraining themselves to one single dimension, we see how a single space can perform its duties either as an online social media profile and/ or through online events during lockdowns and/ or temporarily queering public spaces and/ or having its own full-time venue, etcetera.

Contemporary queer spaces do not exist in a binary system but within the spectrum between the physical and digital, much like the gender identities and sexualities they represent. Contemporary queer spatial production is multidimensional. By queering the definition, planning, and implementation of digital citymaking, this may also become more accessible and achieve a higher outreach. Can this be accomplished by conceptualizing digital citymaking exclusively from a local, urban, material perspective? Or could (queer) digital citymaking be seen as the co-creation of a global social fabric through the production of safe spaces?

References

Anzaldúa, Gloria. (1991): To(o) Queer the Writer — Loca, escritora y chicana. In: Anzaldúa, Gloria; Keating, Ana and Louise; Duke University Press (Ed.) (2009): The Gloria Anzaldúa Reader. Durham.

Babayiğit, Gökalp (2021): “Kann Toleranz politisch sein?“ In: Süddeutsche Zeitung. https://www.sueddeutsche.de/meinung/uefa-muenchen-stadion-regenbogen-ungarn-1.5329619, accessed 14.07.2021.

Campkin, Ben and Marshall, Laura (Ed.) (2017): LGBTQ+ Cultural Infrastructure in London: Night Venues, 2006 - present. London.

Cosgrave, Ellie (2019): The Feminist City. In: TEDx Talks (Hg.) (2019): youtube.com/h?v=rNkB7afesco&fbclid=IwAR1KB5BTUDMzuhYmsq3Mspgrnmh0ozMtkmdBph5mJqXQK8D5UMd1LjyDE4U, accessed 14.07.2021.

D’Erasmo, Stacey (1999): “Out of the Closet and Into the Streets”. In: The New York Times, April 4, 1999. https://www.nytimes.com/1999/04/04/books/out-of-the-closet-and-into-the-streets.html, accessed 16.07.2021.

Doan, Petra L. (Ed.) (2015): Planning and LGBTQ Communities: The Need for Inclusive Queer Spaces. Florida State University.

Dodge, Martin and Kitchin, Rob (2001): Mapping Cyberspace. London. Pp. 17, 21, 52.

European Commission (2021): Press release 15 July 2021: “EU founding values: Commission starts legal action against Hungary and Poland for violations of fundamental rights of LGBTIQ people“. Brussels. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_21_3668, accessed 14.07.2021.

Gestring, Norbert and Janßen, Andrea (Ed.) (2002): Sozialraumanalysen aus stadtsoziologischer Sicht. In: Riege, Marlo and Schubert, Herbert (Ed.) (2002): Sozialraumanalyse. Grundlagen - Methoden - Praxis. Opladen, 149.

Harvey, Gerhard (1989): The Condition of postmodernity. Oxford.

Killermann, Sam (Ed.) (2020): It‘s Pronounces Metrosexual. itspronouncedmetrosexual.com, accessed 15.03.2021.

Kreckel, Reinhard (1992): Soziale Ungleichheit in Deutschland. Opladen.

Rosenzweig, Leah (2018): Cause of death: Uncovering the hidden history of AIDS on the New York Times obituary page, 30 November. In: Craig, David (2020): Pandemic and its metaphors: Sontag revisited in theCOVID-19 era. European Journal of Cultural Studies 1–8. https://slate.com/human-interest/2018/11/aids-new-york-times-obituary-history.html, accessed 14.07.2021.

Sánchez-Molero Martínez, José Miguel (2020a): Master’s Thesis “QUEERingAACHEN. State of the art and potential of queer spaces in Aachen”. RWTH Aachen University. Not published.

Sánchez-Molero Martínez, José Miguel (2020b): Master’s Thesis Annex “QUEERingAACHEN. State of the art and potential of queer spaces in Aachen”. RWTH Aachen University. Not published.

Sánchez-Molero Martínez, José Miguel (2021): “Queer(ing) spaces outside the metropolis: Aachen, a case study”. In: TORCH (The Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities) (Ed.) (2021): Queer Studies Network Blog. University of Oxford. https://www.torch.ox.ac.uk/article/queering-spaces-outside-the-metropolis-aachen-a-case-study, accessed 07.07.2021.

Sontag, Susan (1989): Illness as Metaphor and AIDS and Its Metaphors. New York: Doubleday.