Published 2.04.2025

Plot by Plot

Urban Compounding in Johannesburg

Keywords: Urban typology; organic transformation; as-built drawings; layers of change

Abstract:

This study examines the transformation of the South African version of the Victorian bungalow from a free-standing house into a courtyard type of building – seen as a bungalow compound – as part of wider city-making processes, coined urban compounding. It focuses on changes and conversions in two central suburbs of Johannesburg, Yeoville and Rosettenville. After the abolition of apartheid in the early 1990s, the areas have been almost completely re-populated with radical socio-cultural changes and intensely densified. Methodologically the focus turns to the properties themselves. A series of case studies turn into a knowledge source and developing citational grounds in a grey area between official recordings and lived realities. While the bungalow compounds operate largely individually – plot by plot – the study proposes to understand developing typicalities more categorically through performative groupings that accommodate contingencies, spatially and regulative.

The transforming bungalow in Johannesburg

“If categories are unstable, we must watch them emerge with encounters. To use category names should be a commitment to tracing the assemblages in which these categories gain a momentary hold. […] I need names to give substance to noticing, but I need them as names-in-motion“

(Tsing 2015: 29, 293).

Johannesburg 2024. Hidden behind walls of buildings made in another time and for different people, hundreds and thousands of beds accommodate Johannesburg’s post 1990, transitional, multinational population. Many reside in rooms on private properties with formerly freestanding bungalows from the Victorian/ Edwardian period (Figure 1) in the inner city belt, like in Yeoville and Rosettenville, two central suburbs of Johannesburg. The rule of law treats the mainly non-formal appropriation of the buildings, and more importantly, their yards (that is, the open space on the plot), as a spatial illegality.

Photo: Jeremia Brynard.

In their official accounts, the City continues to record the current multi-unit room arrangements as the former single-family houses. As a result, it identifies them as inefficient in terms of numbers of occupants, and consequently requiring replacement vis-à-vis desired densification (City of Joburg 2016). At the same time, the properties in the well-located areas – if recorded as built and as inhabited (as in this study) – suggest a form of occupation (in terms of quantity, costs, diversity of functions and residents) that the city is actually attempting to achieve (Dormann and Mkhabela 2019). They are also lucrative investments and incorporate multiple providers of other services. Mostly, but not entirely operating off the record, the multi scalar networks that run through these spaces have created their own “infra-economy of material life” in the shadows (Braudel 1981: 24). This rather common form of the everyday in the rapidly urbanising city in the Global South might seem challenging to administer but will nonetheless, most probably, continue to exist. The study’s accounting thus suggests a grey area – and a professional vacuum – between official recordings and lived realities.

Citational Grounds

Methodologically, the focus turns on the properties themselves. As emerging epitomes of house lives/home spaces (Heer 2019; Jenkins 2013) they become knowledge sources and developing citational grounds in a field around the planning of urban accommodation in precarious contexts that is understudied. The approach considers the bungalow compound as an epistemic object (Cetina 2001; Rheinberger 2005; Lury 2021) that can manifest as a problem space across multiple themes, scales, and contexts. In doing so, the study addresses the misconception of architecture as a finished product and appropriates essential incompleteness as a device to locate relevant knowledge(s).

Urban compounding considers the inevitable lack of complete evidence as an opportunity to understand the documentation of these emerging dynamic house worlds as readings of what is and what could be, a concept Simone and Pieterse (2017) refer to as the process of re-description.

The study examines the bungalow compounds via a case study approach. The nearly forensic material recordings of 36 sample plots as particularly complex category of as built documentation with the aim to render the, at times, contested spaces, into valid forms of city building. The use of type as analytical frame has rather morphological connotations than that of building type. While the properties operate largely individually the study proposes to understand developing typicalities more categorically through performative groupings that accommodate contingencies, spatially and regulative. Eventually the paper considers the bungalow compound as part of a of city-making practice termed “plotting urbanism” (Karaman et al. 2020: 1123), a development process that works incrementally plot-by-plot, in rapidly urbanising cities in the Global South and beyond.

With a particular focus on method, the text is organised into six sections. The next section introduces the house as a knowledge object as a central premise of the approach. Then the conceptual reading of the plots through an amended version of the “shaering layers of change” (Brand 1994: 13) is explored as visual, analytical frame to argue for a multi scalar reading of typological change from the ground up. As a next step the individual conversions as uncounted variations are provisionally grouped as a collection of compound doings. These in turn are related back to their underlying geometries, which speak to typological and morphological transformation likewise. The last section reflects on forms of change and urban compounding as a process and product, accommodating the culture of conversion as what is and what could be, in uncertain times.

The house knows

The work starts from the premise that the house knows, and we as professionals don’t, in many occasions. A house is a basic architectural element that is a part of people‘s everyday lives and also a basic unit of urban morphologies. In South Africa the idea of the house is a contested space, as much as the land it stands on (Braun 2015). As private property, the free standing single family residence has played a significant role in the planning paradigm of the country’s historical urban development. Architectural practice here (as elsewhere) has long been complicit in the production and reinforcement of social bias and discriminating spatial arrangements (Bhandar 2018; Aureli 2012; Weizman and Di Carlo 2010). Within a racially oppressive system of unequal distribution of resources, the planning and design professions have inevitably assisted to “craft and spatially define asymmetry” (Aureli and Tattara 2013). Institutionalized and systematically organized, the domestic geometries often appear as the translation of legislation laid out in the past yet retaining some shadow validity as a blueprint in the ground. Within all of this, the City of Joburg continues to ask for the application of, at times, outdated building codes and regulations, drawing on architectural tropes from the past. Additionally, it does not seem to be able to engage with the physical structures as they are – as built – and hence to accommodate the real-life changes which these cater for.

Conversions as aspirational maps

Some buildings/ properties however have managed to help themselves in certain ways – they have learned after they have been built (Brand 1994) and make most of their opportunities for change. Their conversions are, in many ways, aspirational maps (Appadurai 2004: 59; Appadurai 2003) that turn into a blueprint of people’s visions of how they prefer to live within the choices they are privileged to make, overwriting previously set times and boundaries. The bungalow properties are such group of buildings. As a type, the bungalow was the first residential model used in speculative mass housing for middle and working class, after the discovery of gold in the last years of the 19th century (Hindson 1987). Imported via India from colonial Britain, it is one of the most common, most repeated, and most adaptive formal dwelling structures in inner city suburbia of Johannesburg’s central business district. Aerial views display that 65-85 percent of Johannesburg’s early suburbs in inner city proximity are covered with bungalow plots and few variations thereof such as semi-detached or row houses.

The bungalow compound however – as a contemporary form of affordable co-housing, often for migrant population – has not been acknowledged, defined or researched as such. Bungalow compounds are privately owned. Middle and working class bungalows on similar sized plots of 495 square meter that have been transformed into rent per room type of accommodation, often with additional structures, can house up to five times the original occupational density and a variety of uses (Dörmann et al. 2019). In all arrangements, the common denominator is the private yard as a shared communal space.

The role of the yard and small spaces

The role of the yard is an important component, firstly in understanding the typological change from free standing house to court yard arrangement (Rapoport 2007), and secondly to read this obvious change as a morphological transformation with cultural connotations. From the outside still readable as bungalow and additions, the plan shows continuous arrangements of rooms around a series of yards. The yard turns into the void that holds urban lifeforms together in an organic way, and in infinite formations, over time (Figure 2). In terms of embedded house knowledges, the transitions from solid to void, or inside to outside, place a growing emphasis is on key elements that form part of a “geography of small spaces” (Chattopadhyay 2022: 18). These are elements like the corridor, the boundary wall, the laundry line, and obviously the verandah, a most iconic piece of the Victorian import. They all carry political and cultural connotations, often differentiating served and serving spaces, that link across the scales of plot, block, and city.

To make way for new patterns that visually emerge across remaining blueprints and current conversions, the analytical format of the compound recordings is guided by the intention to un-see the house as we know it. Un-seeing the house is to view it as if it did not exist as a pre-classified entity – the free standing house – but rather looking at the bungalow plot as the unit of analysis. The plot is deconstructed into its main elements, and reconstructed as a series of transforming compound. The small spaces and their material parts (the verandah, the stoep, the corridor, the boundary wall) plus infrastructural components (for example the stove and the water tap) are essential informants of the house knowings to reach a better understanding of the emerging urban morphology.

Compound layers

In order to unpack the embedded knowledges systematically the study borrows the principles of Brand (1994) and Duffy (1990) shearing layers of change that start from the premise that “there is no such thing as a building” (Brand 1994: 12). The approach looks at structures in terms of building components and their ability to adapt or change across different time spans. The term was originally coined as a form of facility management related to costs and life span (Duffy 1990). The concept extended into six layers (Brand 1994), each with different rhythms of renewal and possibilities of adaptation: site, structure, skin, services, space plan, and stuff.

The layers analysis permits the addressing of the gap that “will inevitably occur between developing requirements and the residual long-lasting building shell [and the interesting] absence of fit, that is slack” (Duffy and Hutton 2005: 39–40) – as multiple versions of potential and aspiration have been materialised across time. In short, site describes a legally defined lot in a geographical setting and is deemed as eternal. Structure deals with the loadbearing elements of the building, skin refers to the façade, services to infrastructure like water and electricity, space plan is layout and stuff means furniture, fittings, accessories.

Changing hierarchy

Concerning linkages and relationships, Brand (1994) suggests an ordered hierarchy between his layers that the bungalow properties does not follow fully. As illustrated in Figure 3, the research customizes the terms of use, making them particular to the place of investigation, and people in Johannesburg. The study is particularly interested in the role of site and stuff in the context of the bungalow compound. These two layers seem to have a particular deterministic role in Brand’s set-up at each end of the timeline, one being eternal and the other one in constant change or motion. However, due to radical changes in forms of agency that are embedded in both site and stuff in the Johannesburg samples, they seem to be of high significance for what Duffy (2009) calls use potential when applied to the transforming bungalow properties as urban actors.

Where the site previously dominated structure, it is now people’s needs and demands that dominate the site through structure. Where structures previously dominated skin, these are often merged in the bungalow samples and are not separable as building components. In the form of the thickened boundary line facing the public, the skin even becomes an independent service provider, albeit often without official consent and hence partly camouflaged (or paying for protection). Services still, however, dominate the space plan, although stuff in the form of mobile appliances has the power to change that – that is, in principle the space plan does still dominate stuff but it can work the other way around – stuff can amend the space plan, in terms of use.

Bungalow anatomy

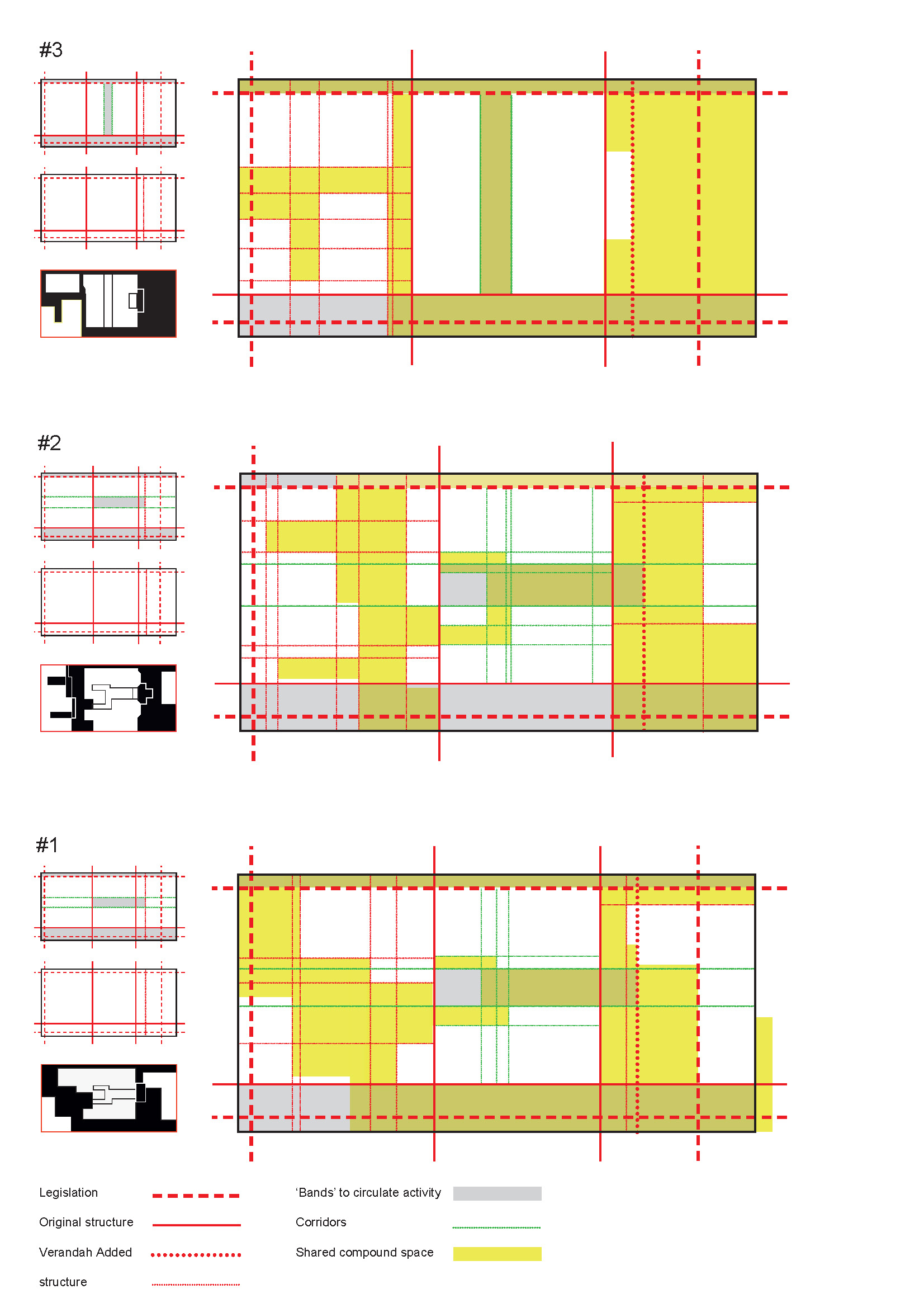

The bungalow compound‘s changing layout and organisational structure describe the basic shift from the house on the plot to the plot as a compound house and merge interiority with exteriority, and the architectural type with urban morphology, by shifting from prescribed functionality to sequences of previously defined elements such as walls, rooms and corridors. The bungalow compound anatomy is then represented in three layers, as illustrated in the diagrams of Figure 3:

- stuff on site, looking at the transforming space plan through domestic practice,

- services, space plan and key built elements to interrogate the role of small spaces, and the repurposing of the initial double life of served and serving,

- skin and boundary wall as the envelope of the void, to explore the form and significance of the emerging courtyard.

The empirical work was initially randomly sampled, and turned purposive on a plot by plot basis between 2018–2020, unpacking and mirroring the transformation practices of the bungalow properties themselves. This method mimics a practice of city-making termed “plotting urbanism” (Karaman et al. 2020: 1123), which describes a process of urban development that works incrementally, from property to property, in rapidly urbanising cities in the Global South and beyond.

Plotting urbanism

The concept permits us to deal with overlapping forms of formal and non-formal urban growth through repeated and similar incremental building activities on private properties in low-income, highly dynamic neighbourhoods, such as in this study. The above authors use this term to describe how forms of ownership vary, how preferred typologies are linked to the commodification of existing houses, how change is a response to the speculative land market (supply on demand) plus landlords, and how tenants often have social relationships that are governed by physical proximity (Karaman et al. 2020). A similar spectrum is covered in the overall study of the bungalow compounds, with the clear intend to undermine the dominance of built form in favour of morphological workings and the embedded intelligence of social life forms.

Key sample: The Roving Kitchen

As a key sample, Case Study #1 The Roving Kitchen illustrates the process below, see Figure 4. All case studies have similar pages in what the study coins the Catalogue of Possibilities. Each set of illustrations is accompanied by an extended single property description. The property has developed a layout that merges traditional domestic indoor activities with outdoor spaces and overlaps public and semi-private areas in a rather fluid way. While the boundary wall has thickened up physically, it has equally softened as a border, both to the street and on a neighbouring side. Management of the plot, and its development stay within the extended family of the owners, as has the construction process of extensions. The programme has changed over the years, from single-family residents to shared rental accommodation, blended with home businesses, kindergarten, and most recently, a restaurant. The centre of the compound is the front verandah, as a threshold between public and private programmes and as a point of control, as both street entrances can be monitored from that position. The manager of the property, the owner’s son or a cousin, stays in one of the newly built units in the front, directly opposite the verandah and use the semi open space as their personal anteroom.

A key element of the change on this property is the moving kitchen, the stove, and the adjoining dining room. Due to racial divisions, the kitchen was initially placed at the back of the property (SE corner). It was part of the serving spaces, operated by black employees who needed to be as invisible as possible in the white neighbourhood, and in close proximity to the servant accommodation along the back wall and the dining room. It then moved to the former ‘hall’ corridor space, as a communal cooking facility has been fitted with appliances and utensils by the landlord, with the verandah as an eating space. Due to a growing demand for more smaller eateries in the neighbourhood, the kitchen turned into a public restaurant and moved to the front, as an extruded boundary and a hole in the wall. The lunch table is placed in the courtyard below the verandah, and the sidewalk, as an extension of the property, accommodates the takeaway cue. The extruded boundary wall at the front has turned into a second skin inside the plot and opens up to the sidewalk. The research refers to this fairly typical shop type as eye height porosity, which fuses here with the open to sky rooms – in this case, the new dining room and the access control space.

Compound doings: plot-by-plot groupings

While the bungalow compounds have been investigated on a case-by-case basis, as so called ground samples, the work is further interested to understand the bungalow compound life strategically, and in what the properties do as a collection. As “non-canonical stores of knowledge” (Chattopadhyay et al. 2020: 2), and largely undocumented, they take shape as forms of change through the intricacy of their current operations – their doings. To give names to these workings is an attempt to capture the transformation as a process, in progress (Tsing 2015). The study considers the sum of what happened in any individual bungalow compound as a basis for the configuration into groupings as developing urban registers “charged and enacted in the sticky materiality of practical encounters” (Tsing 2004: 14). In essence, it is the compound in context, including the experiences and local practices of the environment. Carl (2011) refers to it as the typicality of site, and in a particular situation which generally refers to what is happening in a particular place at a particular time.

Typicality (as opposed to typology) encompasses experiences and local practices that are linked to a particular – typical – spatial configuration that hold morphological connotations (Carl 2011). Following the most common distinctions in typological classifications that have been based on use (programme) and / or morphology (layout) of the architectural object (Forty 2000), the compound groupings are based on what happens on and with the properties, e.g. as mixed use places of accommodation and business, as neighbourhood networks, as investments on the property market, as infrastructural objects. The groupings are thus approached as performative and relational forms of temporary categorisation, in a spatial and regulative context.

In terms of the programme, the transforming properties have remained mainly residential, albeit with many differing forms of accommodation, or have turned into mixed-use, often as contemporary versions of the traditional/initial shop-house. This means that, in principle, we have a blueprint of demarcations in the ground, a sort of one fits most pattern, and a programme that (generally speaking) has not changed in nature, but most certainly in detail. A major switch albeit it the turn from use to exchange value, meaning that the properties are in majority income generating business as opposed to a family residence of the owner (Dörmann 2020).

Compound doings thus describe typicalities as forms of urban change on private grounds, where plots become house and rooms become currency, each playing a particular role across the compounding spectrum. Most case studies find themselves in more than one situation and so loosely fit in more than one of the five groupings – merging, re-scaling, sleeping, enfolding and yarding. Combined, they capture an essential part of the complexity of knowledge the bungalow properties hold, illustrated as overview in Figure 5.

Merging

Merging deals with the composite nature of compounds (Dörmann and Mkhabela 2019), and focuses on how the different parts, elements, activities, people, and processes are related, or relating, to each other and sometimes turn into something new. The attention is on the softening of boundaries in particular of the house, property, understanding of ownership, shared spaces, roles of people, institutions, and the law. Merging introduces, for example, two main kinds of porosity that the bungalow compounds have cultivated – top-down as voids, open to the sky and eye height perforations as inside-out transitions across walls. Merging is often seen in action as cross-programming. Merging also relates to networks and relations people establish in the running of the properties as generators of value. Transgressions are considered here as an operational necessity and require one to withhold or reconsider judgment.

Re-scaling

Re-scaling is considered a (bottom-up) continuation of the land surveyor’s work in the bungalow compound layout, albeit more complex. It addresses issues of size, scale, capacities of smallness (Chattopadhyay 2022), and the altered distinctions of former served and serving spaces. These processes work both from the outside in and the inside out. In a plot-by-plot manner, the house is subdivided into one home per room, with beds as measuring devices. These extend in various ways onto the plot, which then – as a newly configured entity – turns into a courtyard form of house. While the rooms (in the house) remain physically mostly as they were, the in-between spaces have been reconfigured, often by the residents and/ or the owner, to provide privacy, control or channel comings and goings, absorb services and infrastructure, maintain productive distances. The interventions and demarcations are often small or invisible to outsiders and do not necessarily appear on a plan. They are contours of sharing embodying social relations, economic ambitions and limited resources. Re-scaling works on contingencies and translates hierarchies and values that make sense to those who enact them in everyday practices. In the next step, it also introduces a discussion about the scalability of bungalow compound knowledge.

Sleeping

Sleeping describes (aspects of) properties that seemingly remain unchanged. A sleeper looks like it is doing nothing – or not much different – since inception: housing a single family on private grounds, with a verandah and some green around it. While that might be true for some (indeed fewer and fewer) of the properties, sleepers are also active parts of real estate portfolios, waiting to be flipped and traded (see explanation of terms later). They hold potential, and they stay relatively still, suggesting stability. The investment here is time, to make the most of their transactional value. To some extent, the generally low occupancy of sleepers balance out increasing densities of the wider context while compounding interest on the capital base. Physically, they are in pre-compound physical stages, although economically, they may or may not have switched from use to exchange value. Sleepers are, at times, difficult to decipher in their trajectories. Rapidly becoming the exception rather than the rule, their existence permits a measure of urban change.

Enfolding

Enfolding looks at the extruded boundary line over time, in the front of the property and/or on the threshold between public and private space. With the transformation of the hole in the wall into small-scale commercial entities, supplying urban services as a direct response to very local demands and as a new three-dimensional façade, these structures operate as protective envelopes (Chattopadhyay 2022) – or are the houses ultimately besieged? They are certainly rendered invisible at eye height. Enfolding interrogates the activation of the street edge as urban space take over, and the effect of the elimination of the front yard into the inside of the house and also changing forms of street life.

Yarding

Yarding is the practice of providing outdoor space to living beings for activities that usually happen indoors. It is one of the main spatial characteristics of the bungalow compounds - and also the category manifested in most individual formations. There is not a single pair of properties detected with the same yard space and yard usage in the areas under investigation. While the mainly residential properties use the open space as an extension for domestic life practicalities as well as social encounters, there are what the research calls parallel services, in the lack of, or in addition to, state-run communal facilities, such as schools, skill centres, churches. These services/ programmes require outdoor spaces for different reasons to register and operate legally. Yarding, as a contribution to urban life, renders the void into an active form, the other house, that responds to the need for adaptability and flexibility of compound life.

Lines and layouts

Over time, the compound doings have proactively amended norms established at different times for other people and developed (power) relations that run parallel to official forms of governance through negotiated points of contact. In relation to the physicality of the properties, they organize themselves literally along a series of lines, that have been laid out over time, by building regulations, racial segregation and day to day practicalities, like the width of a car.

The compound study aims to understand this composition of lines made by peoples’ lives: as planned, as built, and most importantly, as appropriated as underlying systems of organization – across the transforming properties.

As a series of systems, the compound plots organize and reconfigure themselves along these lines, and design new geometries which are absorbing daily routines, people and their stuff, offering services, directing flows of capital, air and water, and most of the time, but not always, keeping an eye on basic health and safety. Essentially, they graphically describe what underlies the transformation from a freestanding house to a courtyard/ compound arrangement, and the scale of the new urban orders.

Geometries of the plot

To understand the current geometries of change, we take a short look back to the beginnings. As mentioned earlier, the bungalows started their lives on the ground in Johannesburg as a rather large group of similar nuclear family houses, with some place for controlled difference and bit by bit extensions. The basic layout typically translated as a plan divided into two (often equal) halves, with a central passage and rooms on each side, a verandah in the front or wrapped around sideways, service rooms at the back, a driveway on one side and the fire distance set-back on the other. All this exists under low-angled variations of (what became signature) pyramid roofs, with pitched insertions on one side or another. The service rooms, like the kitchen and bathroom, under lean-to roofs at the back of a house, were often the first extensions in the first years of the properties’ lives, different from the outdoor rooms for servants and services along the rear boundary wall. Corridor variations are shown as T, L, and H II shapes. The general room width (between three and four meters) not only renders the spaces larger than smaller but also makes their use interchangeable and thus provides flexibility. In addition, it matches approximately the outdoor driveway width. This indoor/ outdoor match also applies to the central corridor, which is equivalent to the outdoor fire distance setback.

Bands of development

The old and new additions along the now thickened boundary lines echo these dimensions as well, often in a perpendicular direction. Bands with spaces of circulation for activities, people, and staff alternate and print spatial patterns into the ground that loosely fit most of the properties in variation. The blueprint of the layout does not necessarily distinguish between inside and outside spaces. Nor do some of the activities take place. The illustration below explores the emerging pattern across Case Study #1, #2, #3, highlighting the shapeshifting yard with bands as spaces of circulation for activities, people, and staff (Figure 6).

Lifelines of adaptation

The corridor has remained unchanged on most properties and is the element that permits the subdivision of the house into rooms as single units. It is the lifeline for internal adaptations, and at the same time, provides room for flexibility, that is, the set-up of different physical arrangements (Rabeneck et al. 1974; Schneider and Till 2005). The circulation space is centrally positioned and slightly larger in size to allow for a smooth transition to an internal service spine or a series of bathrooms and kitchens. This setup also enables the rooms of the freestanding single-family house to become independent entities as units that can be accessed from the outside. Another adaptive scenario is the conversion of the entrance hallway, a rather grand name for the entrance portion of the corridor that is often slightly wider. The half metre meter of extra width is able to absorb a kitchen counter and can thus turn into a shared utility space.

Most of the properties have also maintained the position of openings to access the plots – both pedestrian and vehicle gates – as they existed for decades. The movement across the plot and designated destinations has changed, multiplied, and redirected. The initial space for the driveway (now used for the programme in 70 percent of the case studies) and the thin narrow passage between properties as a result of fire distance regulations (used by 25 percent) have been repurposed as outdoor passageways and are of high value.

The back of the properties is not anymore lesser than or reserved for a particular kind of people as under the Apartheid regime. Invisibility is now a choice and, at times, a desired quality. The void has many forms across the bungalow properties, with a code of use that is not easy to access for visitors to understand, nor is it uniform across neighbourhoods.

Forms of change

The provisional findings of this study, understood as a catalogue of possibilities, hold relevant concepts of development in the making. As life after on (or in) what was before they deal with appropriation and adaptation as knowledge from the ground, imaginaries tested in the everyday – that in turn might be worthy of being appropriated in the architecture of future planning and urban accommodation, in these areas or similar applicable contexts.

What has been introduced in this study as compound doings – merging, re-scaling, enfolding, yarding, and sleeping – are forms of flexibility and adaptability that exceed the house as an object and transcend the old social-spatial hierarchies on the plot to create alternative ways of arranging and sharing spaces. This profiles the bungalow compounds as architectures that challenge the city in terms of its restructuring. The properties’ operations are addressing new forms of production and institutional orders through modes of cultural and physical appropriation and often share wider economic interests. The question of type enters the realm of urban morphology, as a developmental strategy on private properties that is only very partially orchestrated by the public sector. The doings are thus descriptions of change as a process in formation and are an integral part of the specifics of how the properties tend to behave within the limits of the plot and beyond.

The study of the transformed bungalow in the context of urban densification comes at a time when its existence faces major challenges but also explicit opportunities. In the light of manifestations of both urban management and housing crisis in the inner city of Johannesburg (Zack and Charlton 2023), there is a high demand for affordable accommodation, yet little knowledge about space-sharing practices on private properties (Charlton 2019). The mere recognition of the bungalow compound as a unit in official documentation could support the understanding of their potential within the urban context. The curation of knowledges that are embedded in the transforming bungalow compounds addresses the need for the merging of disciplines and working in inter-disciplinary or trans-disciplinary ways, as much as the properties are merging urban programmes and boundaries. Architecture, planning, and urban design are all shifting practices that have not yet found their role in areas under investigation or similar neighbourhoods. The incorporation of the bungalow knowledges as spatial patterns, as a transforming building type and as new figurings and forms of occupation into urban and town planning policies would require further studys, and efforts of engagment as a way forward.

Urban Compounding is based on the author’s PhD, completed at the University of the Witwatersrand in 2024. Extracts have been published as per University requirements in a book chapter and conference proceedings. The work makes use of original drawings. The catalogue pages are collaborations of the author with Sarah de Villiers.

References

Appadurai, Arjun, (2003).: Illusions of permanence: interview with Arjun Appadurai by Perspecta 34. Perspecta, 34, 44-52.

Appadurai, Arjun (2004): The Capacity to Aspire: Culture and the Terms of Recognition. In: Rao, Vijayendra and Walton, Micheal, (eds). Culture and Public Actions. Palo Alto, California: Stanford University Press, 59–84.

Aureli, Pier Vittoro (2012): The Common and the Production of Architecture: Early hypotheses. In: D. Chipperfield, David, Long, Kieran and Bose, Shumi (eds.) Common Ground: A Critical Reader. Venice: Marsilio Editori, 147–156.

Aureli, Pier Vittoro and Tattara, Martion (2013.): Barbarism begins at home: notes on housing. In: Dogma 11. London: AA Publications, 96–100.

Bhandar, Brennar (2018): Colonial lives of property: law, land, and racial regimes of ownership. Durham: Duke University Press.

Brand, Steward (1994): How buildings learn, what happens after they’re built. New York: Penguin Group, Penguin Books USA.

Braudel, Fernand (1981): Civilization & Capitalism 15th-18th Century: The structures of everyday life, the limits of the possible. New York: William Collins Sons & Co Ltd, Harper &Row, Publishers, Inc.

Braun, Lindsay Frederick (2015): Colonial Survey and Native Landscapes in Rural South Africa, 1850–1913. The Politics of Divided Space in the Cape and Transvaal. Leiden: Koninklijke Brill NV.

Carl, Peter (2011): Type, field, culture, praxis. In: Architectural Design, 81(1), 38–45.

Cetina Knorr, Karin (2001): Objectual Practice. In: Schatzki, Theodore R (ed). The practice turn in contemporary theory. London: Routledge, 175–188.

Charlton, Sarah (2019): Learning from low-income living in an inner-city suburb to inform policy. In: Bénit-Gbaffou, Claire, Charlton, Sarah, Didier, Sophie and Dörmann, Kirsten (eds). Politics and community-based research: perspectives from Yeoville studio, Johannesburg. Johannesburg: Wits Press, 209–232.

Chattopadhyay, Swati (2022): Architectural History or a Geography of Small Spaces? In: Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, March, 81(1), 5–20.

Chattopadhyay, Swati; Wilson, Mabel and Christensen, Peter (2020): Platform. https://www.platformspace.net/home/unlearning-part-i, Accessed 25.2.2025.

City of Joburg; JDA and Rebel Group (2016.): Johannesburg Inner City Housing Implementation Plan (ICHIP) 2014-2021, Johannesburg: City of Johannesburg.

Dörmann, Kirsten (2020): Urban Compounds: Densifying Bungalows in Johannesburg. In: Margot Rubin, Margot,Todes, Alison, Harrsion, Philip and Appelbaum, Alexandra (eds). Densifying the City? Global cases and Johannesburg. Northampton, Massachusetts: Edward Elgar Publishing, 168–178.

Dörmann, Kirsten; Matsipa, Mpho and Benit-Gbaffou, Claire (2019): My place in Yeoville: housing stories. In: Bénit-Gbaffou, Claire, Charlton, Sarah, Didier, Sophie and Dörmann, Kirsten (eds). Politics and community-based research, perspectives from Yeoville Studio, Johannesburg. Johannesburg: Wits Press, 153–160.

Dörmann, Kirsten and Mkhabela, Solam (2019): Urban Compounding in Johannesburg. In: Bénit-Gbaffou, Claire, Charlton, Sarah, Didier, Sophie and Dörmann, Kirsten (eds). Politics and Community-Based Research. Johannesburg: Wits Press, 161–178.

Duffy, Frank (1990): Measuring building performance. In: Facilites, 8(5), 17–20.

Duffy, Frank and Hutton, Les (2005): Architectural Knowledge, The Idea of a Profession. 2nd ed. London, New York: E& FN Spon, an imprint of Routledge; Taylor&Francis e-Library.

Duffy, Frank (2009): A Walk with Frank Duffy [Interview 8 July 2009]. https://urbanomnibus.net/2009/07/a-walk-with-frank-duffy/, Accessed 26.2.2025.

Forty, Adrian (2000): Words and Buildings: A Vocabulary of Modern Architecture. 3rd ed. reprint paperback 2019 ed. London: Thames & Hudson.

Heer, Barbara (2019): Cities of Entanglements: Social Life in Johannesburg and Maputo Through Ethnographic Comparison. Bielefeld, Germany : Bielefeld University Press.

Hindson, Mark R (1987): The Transition between the Late Victorian and Edwardian Speculative House in Johannesburg from 1890-1920, Johannesburg: University of the Witwatersrand.

Jenkins, Paul (2013): Urbanization, Urbanism, and Urbanity in an African City: Home Spaces and House Cultures. 1st ed. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Karaman, Ozan; Sawyer, Lindsay; Schmid, Christian and Wong, Kit Ping (2020): Plot by Plot: Plotting Urbanism as an Ordinary Process of Urbanisation. In: Antipode, 52(4), 1122–1151.

Lury, Celia (2021): Problem Spaces, How and Why Methodology Matters. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

Rabeneck, Andrew; Sheppard, David and Town, Peter (1974): Housing flexibility/adaptability? Architectural Design, 44(2), 76–91.

Rapoport, Amos (2007): The Nature of the Courtyard House. In: Traditional Dwellings and Settlements Review, 18(2), 57–72.

Rheinberger, Hans-Jörg (2005): A Reply to David Bloor: Towards a Sociology of Epistemic Things. In: Perspectives on Science, 13(3), 406–410.

Schneider, Tatjana and Till, Jeremy (2005): Flexible housing: Opportunities and limits. In: Architectural Research Quarterly 9 (02), 157-166.

Simone, Abdou Maliq and Pieterse, Edgar (2017): New Urban Worlds: Inhabiting Dissonant.

Tsing, Anna (2004): Friction: An Ethnography of Global Connection. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Tsing, Anna (2015): The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Weizman, Eyal and Di Carlo, Tina (2010): Dying to speak: forensic spatiality. In: Log, Anyone Corporation, Volume 20, 125–131.

Zack, Tanya and Charlton, Sarah (2023): The City of Johannesburg does have an inner-city housing plan – it just hasn’t implemented it. Daily Maverick, 5 September2023, Johannesburg.