- Start

- Of closure and reuse

- A new lease of life for department stores

- A process of decline

- City centre changes and a new lease of life for department stores

- Collaboration and the role of interim uses in urban development

- The case study: aufhof in Hanover

- From consumption to collaboration?

- A proactive public administration, a web of interests and a dearth of strategies?

- Limitations of an interim use as an instrument for urban development

- What’s next: the long-term vision for the aufhof

- About the author(s)

- References

Published 2.04.2025

From Consumption to Collaboration?

A Closer Look At the Interim Use Project aufhof in Hanover‘s City Centre

Keywords: Department stores; reuse; temporary uses; participation; stakeholders

Abstract:

The closure of the Galeria Karstadt Kaufhof in Hanover led to an interim use project entitled aufhof, which featured a range of events. This study explores how interim uses can become sustainable, long-term solutions, focusing on the role of department stores in German city centres. The research highlights the potential for reusing vacant department stores, emphasising the need for collaboration among stakeholders and addressing ongoing changes in consumer behaviour. Through a literature review, participant observation, media coverage and interviews, the authors examine the interim use of the former Galeria building. The project, initiated after the building’s closure, hosted various events and exhibitions, illustrating both the successes and challenges of interim uses in urban development. Despite the success of the interim use project, the future of the building remains uncertain, highlighting the need for a long-term strategy.

Of closure and reuse

Following the closure of the Galeria Karstadt Kaufhof at the end of September 2022, various stakeholders, including the City of Hanover and the Hanover University of Applied Sciences and Arts (HsH), initiated the interim use project called aufhof in the Hanover city centre with a diverse mix of events and themes. At the time, the former owner, Signa Group (Signa), had made the premises available, but the operating costs of the interim use project had to be borne by the stakeholders themselves. In the meantime, there was a change of ownership to a company called AT 2 Beteiligungs GmbH (I2).

"Excuse me, where can I find the suits – are they still on the top floor?" (conversation during the event entitled ‘Plenum: Urban Mixtures – Spatial strategies for repurposing vacant spaces in city centres’ (transl. by authors)) (LHH 2024b). This question came from a man wandering around at an event in the aufhof (LHH 2024a). Starting with this anecdote, it can be assumed that similar stories, conversations and encounters have occurred between former and current visitors, users and stakeholders during the interim use of the department store. This anecdote reflects the fact that former department stores in the heart of the city can be identity-forming places: places of memories or anchor points for its residents (BMWSB 2023: 5; Imorde and Junker 2014: 51). At the same time, the vacancy rate in the city centre reflects changes in shopping behaviour due to the increase in online retail, the abandonment of bricks-and-mortar retail due to consumer restraint, rising rents, the increase in chain stores and, in some cases, strict building and monument protection regulations (BBSR 2024: 63ff.; BMWSB 2023: 9; Diringer et al. 2022: 26ff.; BMI 2021; DST 2021; Klemme 2022: 6). These trends are part of the ongoing discussions about the future of city centres in general.

The aim of the aufhof interim use project was to bring together a range of events drawing on the fields of urban development, the built environment, science and innovation, and to promote networking among stakeholders (I3). The primary goal was to facilitate encounters and to discuss the future of the city centre by bringing together various stakeholders under one roof (ibid.). For example, the event "Plenum: Urban Mixtures – Spatial strategies for repurposing vacant spaces in city centres" (LHH 2024b), which took place in June 2024, addressed the pressing question of how a change of use might be possible without demolition. The answer was: We can, but ... The but emphasises the urgency of the research question: how an interim use can be converted into a long-term, sustainable project, using the example of the aufhof as a case study. The focus will be on the initiators of the project, their goals and intentions and how the collaboration between the various stakeholders took place.

The discussion on transformation – not only in the context of urban development or interim uses – intensified in 2011 with the report from the German Advisory Council on Global Change (WBGU) on "Great Transformation" (WBGU 2011). Today, transformation encompasses more than just economic aspects – it also includes socio-ecological perspectives. "However, the Great Transformation is less about headline projects. Instead, it is more about varied, interconnected, small-scale and systemic transformations. These occur at different levels of spatial development and its associated activities, and each within a certain socio-ecological context" (Grabski-Kieron and Greinke 2024: 3). Since there is no single conclusive definition of transformation (ibid.), in this article we deliberately relegate such complexities to the background and instead address the issues of conversion and change. This refers to the change from one phase of use to another and explicitly includes various perspectives: social, spatial, ecological, economic, cultural and so on.

The article starts with a short overview of the history of department stores, followed by the role of department stores in (German) city centres and current discussions about interim uses in urban development processes. The subject of interim uses was studied by an analysis of the titles of the literature, sourced via Scopus, Mendely and Google Scholar (following Brink 2013: 46–48). This search of the literature focused on the future of (inner-)city centres, the reuse of department stores and shopping centres, collaboration and participation in urban and city-centre development and the city of Hanover as the site of aufhof. Searches using these terms yielded 1,040,000 hits for city centres, 553,000 for stores reuse, 5,710,000 for urban development participation, and 1,440 for aufhof Hanover. Selected titles and abstracts were read, and chose specific articles to use for the analysis. In addition, more exploratory research were undertaken. Various media sources, including newspaper articles, blogposts or the official website of the City of Hanover, were analysed and integrated into the analysis. Furthermore, the authors conducted participant observation from the beginning of the aufhof interim use in June 2023 until July 2024 (following Bachmann 2009) by making several irregular visits, attending around 15 events with a focus on urban development and taking photographs. Based on this, in 2024 qualitative, semi-structured interviews (following Meuser and Nagel 2002) were conducted with four major stakeholders involved in the interim use. The interviewees were representatives from the City of Hanover, the HsH, programme creators and experts in public participation in Hanover. Semi-structured guidelines were developed to ensure a dialogic structure during the interviews (Liebold and Trinczek 2009: 35–39; Helfferich 2011: 36). The interviews focused on three main topics: the constellation of stakeholders, the nature and degree of the collaboration between them and their interdependencies; the role of interim use as a planning instrument; and strategies for the subsequent use. The interviews lasted from 25 to 40 minutes and were then subject to a qualitative content analysis (following Mayring 2010). We describe how we collected the empirical data and then delve into the case study, with a special focus on the stakeholders involved. The analysis and results are discussed in the last sections, followed by a conclusion and thoughts on the future outlook.

A new lease of life for department stores

The history of large department stores in Germany dates back to the 19th century (BBSR 2024: 10). By definition, department stores are retail outlets that offer a wide range of goods in a large area, usually comprising 3,000 square metres or more of sales space (Statista 2024a). Most department stores are centrally located in the city centre. The emergence of department stores offering a wide variety of goods under one roof for a broad consumer group marked a significant shift in retail enabled by industrialisation and the industrial production of goods (Hangebruch 2020: 171; Landesinitiative StadtBauKultur NRW 2020: 07). This development continued in the second half of the 19th century: the KaDeWe (Kaufhaus des Westens, the department store of the West) opened in Berlin in 1907, while other well-known department stores in that period were Tietz in Gera and Schocken in Zwickau (Landesinitiative StadtBauKultur NRW 2020: 08; Imorde and Junker 2014: 49). The retail concept continued to grow and flourish until the First World War (Hangebruch 2020: 171). Under National Socialism, there were massive upheavals in the ownership structures of department stores, most of which were founded by Jewish merchant families (Landesinitiative StadtBauKultur NRW 2020: 08; Imorde and Junker 2014: 49ff.). The reconstruction phase after the Second World War ushered in a new heyday of department stores, which expanded from the 1950s before peaking in the 1970s, when Germany had around 1,150 of the stores (Imorde and Junker 2014: 49ff.). They began to decline from the 1970s due to changes in consumer behaviour and the emergence of other large-scale retail outlets such as shopping centres and hypermarkets in the 1990s (ibid.). Today, many city centres in Germany are facing numerous challenges owing to various changes (Klemme 2022: 5; Rieper and Schote 2022: 4). Not only changes in purchasing behaviour, but also the increase in online retail, the closure of stationary retail stores due to consumer restraint, rising rents, a growing number of chain stores and ever more frequent crises (e.g. the environmental crisis, Covid-19, war, etc.) are increasingly exacerbating these changes (BBSR 2024: 62; ZiA 2023; Bundesstiftung Baukultur et al. 2020; BMI 2021; DST 2021).

A process of decline

The four biggest trading groups in Germany in the 1990s were Karstadt, Kaufhof, Hertie and Horten. The gradual decline in department stores came about through the merging of the four largest department stores into two trading groups, Karstadt and Kaufhof, in the mid-1990s (Hangebruch 2020: 172ff.; Landesinitiative StadtBauKultur NRW 2020: 13; BBSR 2024: 22). The crisis is particularly evident in the example of Karstadt, formerly Germany’s largest retailer: from 1994 the Hertie department stores were enfolded into Karstadt, and were either gradually renamed Karstadt or closed. After the merger with the mail order company Quelle in 1999, the group, now trading as KarstadtQuelle AG, got into financial difficulties around 2004, as a result of which it sold 74 stores to the British financial investor Dawnay Day in August 2005 (Landesinitiative StadtBauKultur NRW 2020: 13). Karstadt went bankrupt in 2010, which led to further closures. Between 1994 and 2019, 219 of the 394 department stores in Germany were closed (Hangebruch 2020: 172ff.). In 2018, eight years after the bankruptcy of Karstadt, the two large department store companies Karstadt and Kaufhof were merged into Galeria Karstadt Kaufhof GmbH (ibid.: 173). According to research by Hangebruch (2020: 174) of the 219 department stores that closed, 183 were abandoned and 20 were under (re-)construction as of 31 December 2019.

City centre changes and a new lease of life for department stores

The development of department stores is embedded within the spatial context of city centres (BBSR 2024: 63). Discussions about the future of city centres and criticism of their monofunctional use have gained momentum, especially due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Discussions in academia and in planning practice advocate for a multifunctional use of city centres, with the aim of incorporating additional amenities such as cultural and social activities, services and leisure facilities alongside retail and supply functions (BBSR 2024: 69; Diringer et al. 2022: 19). As hubs, other functions – such as communication and integration, as well as green and open space functions – are gaining importance in city centres (Diringer et al. 2022: 35). Department stores that emerged during the economic boom are both witnesses to and symbols of that era. At the same time, they are associated with car-oriented and consumer-focused urban development (BMWSB 2023: 9; Landesinitiative StadtBauKultur NRW 2020: 9). Current challenges, such as climate change and the resulting need for a shift in mobility, as well as changing consumer behaviour, necessitate a rethinking and repurposing of department stores, multi-storey car parks or office buildings. Due to their central location, department stores have an important place-making and anchoring effect (ibid.: 11).

In 2021, the German construction industry was responsible for greenhouse gases amounting to around 4.2 million tonnes of carbon dioxide (CO2) equivalents (Statista 2024b). The urgency to act and to reuse existing buildings and building material is inevitable. Discussions about the reuse and revitalisation of department stores have been ongoing since the 2010s (Imorde and Junker 2014; Hangebruch 2020). Challenges such as complicated ownership structures and the limited influence of local authorities on this process are still pressing questions. As stated in the introduction, the goal of reusing the existing structure is possible, but doing so is technically complex and often a lengthy process. Furthermore, a change in the patterns of reuse of department stores can be observed, focusing more on mixed-used structures (ibid.). Their reconstruction and modernisation not only enable a new lease of life for the buildings but can also further develop the identity of the place (Hangebruch and Othengrafen 2022: 1). Department stores are often unique buildings and thus contribute to the identity of a city. Research on the conversion of former department stores in Germany demonstrates that this approach is possible, although the planning, discussion and decision-making processes are often highly protracted (BMWSB 2023: 12; Hangebruch 2020: 174). Furthermore, in response to these tendencies, recommendations have been developed by the Federal Ministry for Housing, Urban Development and Building (BMWSB) (2023) and the German Institute of Urban Affairs (Difu) (Diringer et al. 2022) to support local authorities in shaping city centres. Imorde and Junker (2014: 53) summarise various possible paths of action at the municipal level for transforming (abandoned) department stores: the first point mentioned is to embed the building in any integrated city development strategies, and secondly to formulate future scenarios to give potential investors or owners more planning certainty and to establish a strategic approach. Another important step involves communication with the owner, which can be made more goal-oriented by using a professional mediator between the two parties, for example. Other measures include deploying planning law instruments and activating urban development funds, while a last option to consider would be for the local authority to purchase the building. In the following discussion, our case study is analysed based on these potential action paths. At the same time, looking at examples in Germany, a variety of projects can be noted (BBSR n. d.). Over the last 25 years, Germany has gained experience in the conversion of former department stores, highlighting the fact that it is not a question of if but when (BMWSB 2023: 15; Hangebruch 2020: 171ff.). According to the BBSR (2024: 77), 21 out of 45 department stores saw interim uses between 2020 and 2022. Therefore, we briefly outline the role of interim uses in urban development.

Collaboration and the role of interim uses in urban development

Interim use refers to the creative use of land or buildings by third parties after the original use has been discontinued and before a new use is implemented (Christmann 2015: 3020). This concept has been increasingly relevant since the late 1990s, particularly for vacant lots and unused buildings awaiting redevelopment (ibid.). Formerly only partly tolerated or even criminalised, temporary use became accepted, institutionalised and incorporated into informal planning instruments (ibid.: 3021). Through interim uses, the trickle-down effects of vacancy and the negative impact on the surrounding area are counteracted. A key role is played by the variety of stakeholders involved in the process, often linked to the cultural, creative and innovative sectors, who begin to work with the owner and the public administration (BBSR 2012: 16ff.). Other actors appear and take on the role of mediator. Stakeholders from civil society, artists or cultural professionals put a lot of effort and expertise into interim uses. At the same time, they depend on the owner and the further development of the place. The collaboration between the stakeholders is often asymmetrical from the outset. Nevertheless, this change is connected with the local planning culture and its support for collaboration and co-production in urban development.

The case study: aufhof in Hanover

In the middle of central Hanover, the former Galeria is located in the immediate vicinity of historical buildings like the 14th-century Marktkirche and is close to key locations and shopping streets like Georgstraße, Große Packhofstraße, Karmarschstraße and Bahnhofstraße which had an average rent of 135 euro per square metre in 2021 (Hannover.de 2024a) (figure 1 and 2), illustrating the value of the former department store. After the location was given up in September 2022, demolition plans for the building were announced at the beginning of January 2023. The old building from 1975 is to make way for a new, mixed-use building. Originally, the owner Signa intended to demolish the building and create a mixed-use with modern working environments, publicly accessible areas, a hotel and space for artisanal producers and creative uses from 2024. With the insolvency of Signa and the change of ownership in September 2023, a further interim use could be agreed, but the future of the building is still unresolved.

In response to the closure, an interim use was initiated from May 2023 to December 2023. This interim use was extended from March to July 2024, notwithstanding a change of ownership at the end of September 2023. For the interim use, the ground floor and first floor, comprising 5,000 square metre, were used for various activities such as workshops, gaming areas, exhibitions and events. Due to its success with over 100 events, 190 lectures in its auditorium, 17 major exhibitions, a gaming area which attracted 30,000 visitors and a Banksy exhibition which drew in nearly 100,000 visitors, the decision was taken to extend the interim use until July 2024 (ibid.). The cost for the interim use from May 2023 to February 2024 was around 640,000 euro (LHH 2024c). The project’s extension in 2024 offered a range of summits, international exhibitions, innovation workshops and science talks.

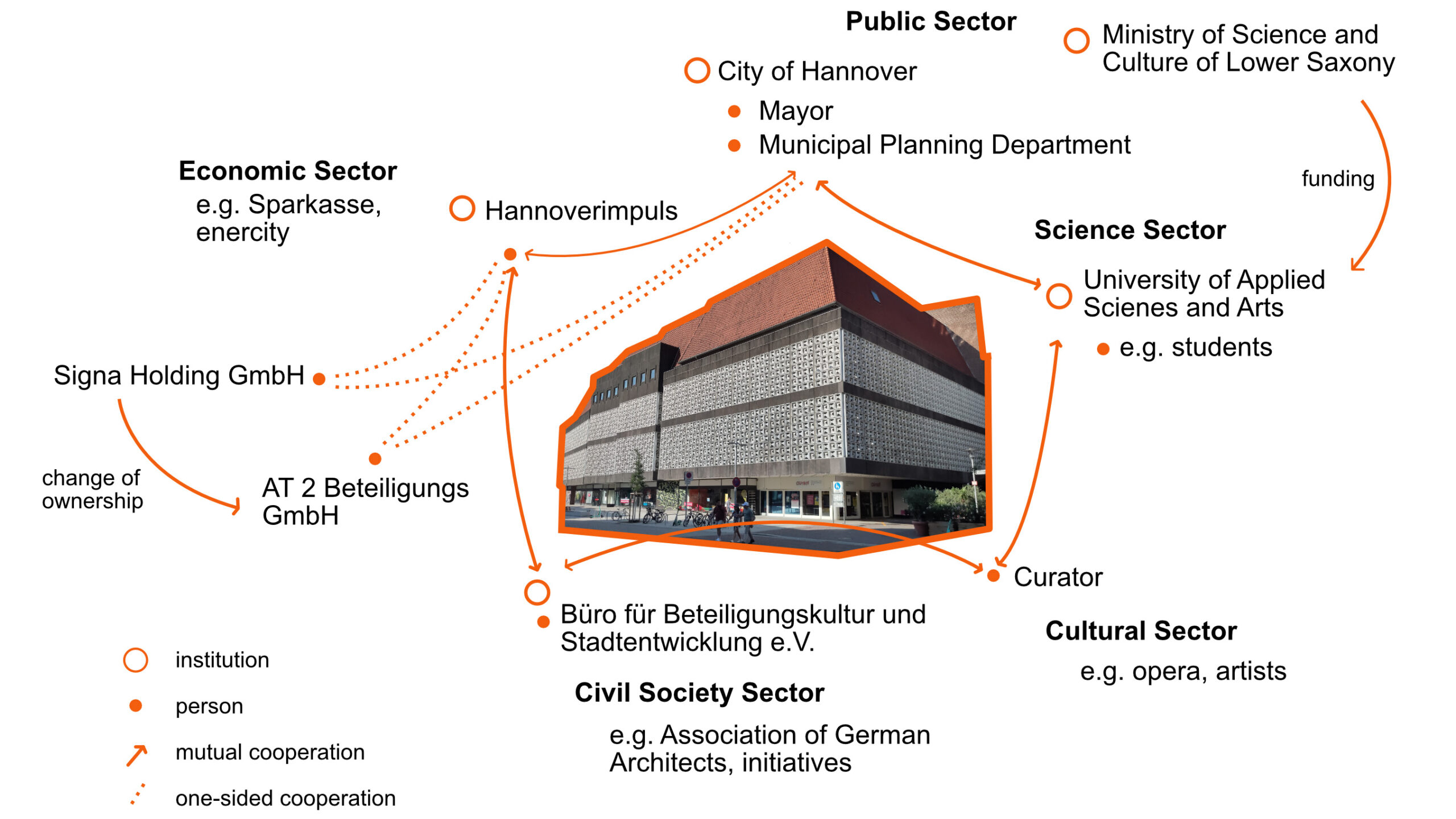

Thanks to a joint effort between the project participants from the state capital Hanover (Landeshauptstadt Hannover, LHH), the HsH – which obtained funding from the Ministry of Science and Culture of Lower Saxony (MWK) for this purpose – and hannoverimpuls (hi), which was in charge of promoting economic development, the project was realised within a few months (LHH 2024c). The collaboration between the city administration, academic institutions such as the HsH, hi and civil society stakeholders enabled the aufhof to be initiated and implemented. The project aimed to create a platform for discussion about the development of the city and its architectural culture, and to foster research, innovation, experimentation and creative approaches to dealing with the challenges of the future. From the conception to the realisation of the interim use, various stakeholders from the public, economic, cultural, university and private sectors were involved (figure 3). In addition, the project organisers were able to secure sponsors such as the local energy company enercity and the Sparkasse Hanover Bank (Hannover.de 2024b). Interested parties such as associations or companies could rent the space and utilise the premises.

From consumption to collaboration?

The aufhof case study illustrates that an interim use can initiate a change but also be a challenge for the stakeholders involved. The circumstances of the Hanover city centre in comparison to other German cities are specific but not unique. On a national and international level, cities have to deal with the conversion of former department stores and their future (Hangebruch 2020: 171ff.). The buildings concerned are often centrally located close to key areas, historical buildings and shopping streets, as the former Galeria building is. This is relevant when considering abandoned buildings as they can have a negative impact on the image and optics of a city when their condition deteriorates or they fall vacant.

A proactive public administration, a web of interests and a dearth of strategies?

In the present case study, the media sources made clear that the owner, Signa, wanted to demolish the building and create a mixed-use complex. But in the meantime, Signa was open to trying a temporary use for the building: it was not necessary for the local authorities – the City of Hanover – to rely on planning law instruments to steer the owner towards the desired objectives. In the interviews this was deemed a lucky coincidence and not the norm (I1); owners or company groups are often not really interested in an interim use for a single building as it is just one of many buildings in their portfolio. With the change of ownership at the end of 2023, the basis for negotiations and the interest in collaboration shifted again, leading to uncertainties (I2-4). From the perspective of one stakeholder, the communication with Signa was described as positive (I2). A Signa staff member came to Hanover once a week for an on-site meeting and responded flexibly to enquiries, thereby facilitating effective collaboration (ibid.). Contact with the subsequent owner proved to be more difficult as the building was being administered by a contracted company which strictly adhered to the letter of the contract. In addition, the company’s head office moved to Frankfurt am Main and a weekly meeting between the initiators and the owners of the building was no longer possible (ibid.).

Despite this, our study of the main actors indicated that the Hanover city administration somehow took over the role of initiator and manager, which, according to Imorde and Junker (2014: 53), results in greater flexibility, responsiveness and transparency, which are crucial for a successful interim use. The city administration initiated and conducted the negotiations with the owner of the building. In addition, the city engaged other stakeholders, such as managers and curators from various sectors (education, culture, business, etc.), so that the aufhof project could be launched, implemented and extended (I1). Although financial and personnel bottlenecks in local authorities often make it difficult to realise innovative and pilot projects (Imorde and Junker 2014: 53), the City of Hanover managed to implement this interim use successfully. A significant financial contribution was made by the HsH through the MWK. The city also contributed funds. According to one interviewee, the investment was worthwhile in light of the success of the project (I3). Various aims were achieved for the stakeholders involved, including: a) the city administration, which had hoped for more visibility; b) the university, which was able to bring science into the city; c) civil society, which had a space in a central location; and d) the surrounding companies, which were able to benefit from the vitality of the location (ibid.).

Overall, as illustrated in Figure 3, the interviewees described the informal collaboration as very positive (I1-4). Although it was not structured or goal-oriented from the outset, it was carried out with a great deal of enthusiasm and commitment (ibid.). According to media reports and the interviews, a small circle of initiators was able to realise ideas they had had for some time in the fortuitously empty shell of the former Galeria building. The ideas and impulses behind the project were already mentioned in the 2016 urban development strategy "My Hanover 2030" (LHH 2016: 36). The interviews made clear that the overarching aim of all stakeholders was the revitalisation of the city centre, the creation of a meeting place open to the public, a space without the urge to consume, and a forum for dialogue and networking which could bring together different types of expertise (I4). Thanks to the collaboration between the initiators, these aims were realised (I3). The most important aspect was the nature of the project and not the building itself (ibid.). The interviewees used expressions such as "the future in the present", "a place of longing" or "an experiential space" to describe what they wanted to create. They described the project as an experiment, a pop-up, improvised and imperfect (I2-4). From the perspective of one interviewee, the project was not totally improvised and parts were consciously steered towards the main objectives. The choice of stakeholders which were part of the initiator group underlines that this constellation was likely thoughtfully chosen and can be traced back to the urban development strategy My Hanover 2030. Nonetheless, the collaboration was also highly dependent on the interests of those involved, which was reflected, for example, in the diminished collaboration after the change of ownership.

The interviews and research into the network of actors suggest that each of the stakeholders pursued a strategy in accordance with their own aims and intentions. There was no integrated long-term strategy to ensure the future of the building and a permanent use. One reason for this might be the tight schedule and the fact that the possibility of an interim use for the former department store arose suddenly (I2-4). During the process, the question arose of how the project could last into the future. One interviewee even described how, when Signa began to back away from the original plans, there was a glimmer of a chance that the aufhof project might ultimately have an influence on the owner and the future development of the building (I3). This glimpse wobbled when a change of ownership took place. An integrated, durable strategy, a notion of how to move forwards and steer the future process – these aspects were not mentioned in the interviews. Currently, an internal working group is collating and summarising the collected experience and knowledge gained from the process.

Limitations of an interim use as an instrument for urban development

Media research (Hannover.de 2024c) and participant observation indicate that the building served as a shell for experimentation. However, the central location of the building, its history and the short timeframe between its closure and the interim use were important factors in making the pop-up-experiment successful (I3). The City of Hanover exploited numerous opportunities and contacted the owner. In a context where budgets are under such pressure, the city also invested personnel costs that could certainly have been fruitfully deployed elsewhere. The project has brought stakeholders into the city centre who were not previously present there (e.g. the HsH). The local hospitality and retail sector has benefited from the revitalisation of the property, which has enhanced its appeal to prospective purchasers (Hannover.de 2024c). A building which is a hub of activity is likely to attract greater interest from those seeking a property in a vibrant location (I1 and 4). Consequently, the analysis shows that the city centre as a place, the city administration as an initiator and the owner as the disposer have all benefited from the interim use. Interim use can serve as a bridging strategy, to at least avoid the deterioration of the building and especially the surrounding areas.

While it can be an option to counteract the problem of vacant buildings, it will not solve the underlying challenges of dealing with the growing number of such buildings in city centres. There are a number of barriers – temporary and long-term – when it comes to the conversion of (abandoned) buildings. There may be more recent regulations to take into account that did not exist when the building was originally developed, such as those in relation to fire safety, accessibility, noise, emissions, structural elements, lighting, ventilation, new applications and so on. The Federal Institute for Research on Building, Urban Affairs and Spatial Development (BBSR 2024: 30ff.) has analysed general and specific conversion-relevant aspects such as urban integration, building height, façade construction, roof shape, parking spaces, vertical infrastructure such as lifts and staircases, room depth, atriums, the load-bearing structure and column grid as well as interior height. All these aspects influence the potential for conversion and reuse. In the case of aufhof, the interviewees stated that the building structure was in poor condition (I1-4), resulting in a difficult working environment. Its structure is similar to other department stores. The negative aspects were the acoustics and the internal flow of the whole space, while the heating and ventilation system was all or nothing. The building was planned to be a single interconnected complex. According to an interviewee, the building has some advantages, such as its modular structure. For instance, it was possible to take out the windows to enable passersby to have a view in. All interviewees distanced themselves from the idea of rescuing the building (I1-4). In the end, interim uses do not lead to reuse per se. Whether the ideas and experiences gained from an interim use will lead to a strategy for reuse is still an open question, and very much dependent on the owner. Interim uses can provide valuable impulses, encourage local authorities to experiment and enable new approaches. Nevertheless, interim uses are also defined by limitations, as they are highly dependent on the engagement of the stakeholders and on the owner of the building, making it difficult to secure sustainable outcomes. For future temporary uses, one interviewee called for more planning certainty, such as longer-term temporary use contracts to enable more professional and targeted uses (I2).

What’s next: the long-term vision for the aufhof

Today there are more reasons than ever to find reuses for former department stores (BBSR 2024: 60). The reuse of department stores within city centres should focus on sustainability from the beginning. Although there are also numerous critical voices, interim solutions are proving successful in many places. They can be an impulse for inner-city development and given their scale they can serve as an exemplar for sustainable property and urban development (BBSR 2024: 61). To be sustainable, however, it is important to develop appropriate strategies.

"Transformation impulses are ghastly and strategies for dealing with them are still in the development phase"

(I1).

The aim of the aufhof project was to create a platform to discuss the development of the city, its architectural culture and built environment with various stakeholders. Nevertheless, the momentum that determined the success of the project was that people happened to be able and willing to work together. There was interest and a huge stroke of luck (I1). A unique aspect of the constellation was the informal network of actors from the private, public, civic and university sectors (figure 4). The university sector is becoming increasingly involved in current discussions, particularly those regarding living labs (Koens et al. 2024; Herth et al. 2024). But the long-term vision for the aufhof is still not clear. There was also discussion about possibly pursuing the aufhof experimental space in another vacant building (Hannover.de 2024c; Wirtschaftsförderung Hannover 2024). For the Galeria building a mixed-use building complex – as the former owner Signa suggested and is often the case (ZiA 2023: 36) – could be a way forward in the future. A classic mixed-use strategy often provides space for retail use on the ground floor because, as already described, the city centre location is predestined for this. The upper floors are often earmarked for non-commercial uses or public-oriented services, for example offices, surgeries, fitness studios or restaurants (Landesinitiative StadtBauKultur NRW 2020: 42). Converting a department store into a mixed-use building is technically challenging but promising. In addition, residential use, at least in part, can also be a conceivable component of such a strategy (ibid.: 43).

Against the background of the history of department stores in Germany, it can be stated that the strategy of interim use is highly relevant in urban development processes today (BBSR 2024: 158). Reusing existing structures in city centres is possible, but a technically complex, long-term process. As a part of informal planning instruments, interim uses involve a variety of stakeholders from the cultural, creative and innovation sectors. As was the case in Hanover, stakeholders generally enter into a collaboration with the building owner and public administration, which shifts the local planning culture from collaboration to co-production in urban development. For temporary uses to be successful, it is therefore important that the city administration supports the project, that politicians agree and that the building owner and manager are an open partner. From the local authority’s perspective, these ducks should ideally be in row before the project is fully conceptualised and initiated, as this is the point at which they still have the opportunity to steer future developments and make planning a collaborative responsibility (BMWSB 2023: 46). In order to preserve the "magic of the pilot project" (I1), it is therefore important that the know-how is documented and evaluated so that no knowledge is lost. Nevertheless, while aufhof was a great starting point for changing the planning culture in Hanover, it remains to be seen whether this impulse towards co-production will last and enhance long-term, sustainable conversion projects and development in the City of Hanover (figure 4). This article can be seen as a starting point for a closer examination of the whole process; during the research, more and more stakeholders and aspects emerged, each of which deserve more attention and analysis. Another aspect that was not further addressed in this article, but is of great importance, is the scope for action that local authorities have vis-à-vis the property owners and developers and the point at which they should consider becoming active stakeholders in purchasing the building.

Centres of the Future – Challenges and Opportunities for Sustainable Development (FutureCentres) is funded by the German Foreign Office (AA) and the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) as part of the University Partnerships between the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki – AUTH (Faculty of Engineering School of Architecture) and the Leibniz University of Hannover – LUH (Faculty of Architecture and Landscape).

We would like to thank all interviewees for their willingness to provide information and their support.

References

Altheide, David L. and Schneider, Christopher J. (2013): Qualitative Media Analysis. 2nd edition, SAGE Publications.

Bachmann, Götz (2009): Teilnehmende Beobachtung. In: Kühl, Stefan; Strodtholz, Petra and Taffertshofer, Andreas (Eds.): Handbuch Methoden der Organisationsforschung. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 248-271. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-531-91570-8_13.

BBSR (Bundesinstitut für Bau-, Stadt- und Raumforschung) (Ed.) (2024): Kauf- und Warenhäuser im Wandel - Kleiner baukultureller Statusbericht.

BBSR (Bundesinstitut für Bau-, Stadt- und Raumforschung) (Ed.) (2012): stadt:pilot spezial. Offene Räume in der Stadtentwicklung Leerstand - Zwischennutzung – Umnutzung.

BBSR (Bundesinstitut für Bau-, Stadt- und Raumforschung) (Ed.) (n. d.): Forschungsprojekt: Kauf- und Warenhäuser im Wandel. Kleiner baukultureller Statusbericht. https://www.bbsr.bund.de/BBSR/DE/forschung/programme/exwost/jahr/2022/innenstaedte-kaufhaeuser/01-start.html, accessed: 16.07.2024).

BMI (Bundesministerium des Innern und für Heimat) (Ed.) (2021): Innenstadtstrategie des Beirats Innenstadt beim BMI. Die Innenstadt von morgen – multifunktional, resilient, kooperativ. Berlin.

BMWSB (Bundesministerium für Wohnen, Stadtentwicklung und Bauwesen) (Ed.) (2023): Innenstadtratgeber. Großimmobilien: Frequenzanker und Raumressourcen in der Innenstadt von morgen. Berlin.

Brink, Alfred (2013): Anfertigung wissenschaftlicher Arbeiten. Ein prozessorientierter Leitfaden zur Erstellung von Bachelor-, Master- und Diplomarbeiten. 5th (expanded and updated) edition. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden.

Bundesstiftung Baukultur, Deutscher Verband für Wohnungswesen, Städtebau und Raumordnung, Handelsverband Deutschland und Urbanicom (Ed.) (2020): Stoppt den Niedergang unserer Innenstädte. Berlin.

Christmann, Gabriela B. (2015): Zwischennutzung. In: Handwörterbuch der Stadt- und Raumentwicklung, 3019-3024. ARL – Akademie für Raumforschung und Landesplanung, Hanover.

Diringer, Julia; Pätzold, Ricarda; Trapp, Jan-Hendrik and Wagner-Endres, Sandra (2022): Frischer Wind in die Innenstädte. Handlungsspielräume zur Transformation nutzen. Berlin: Difu-Sonderveröffentlichung.

DST (Deutscher Städtetag) (Ed.) (2021): Zukunft der Innenstadt. Positionspapier des Deutschen Städtetages. Berlin/Köln.

Grabski-Kieron, Ulrike and Greinke, Lena (2024): Spatial research on rural areas in the context of socio-ecological transformation. In: Grabski-Kieron, Ulrike and Greinke, Lena (Eds.) (2024): Rural Geographies in Transition. Rethinking sustainable futures of rural areas. Rural areas: Issues of local and regional development, LIT Verlag.

Hangebruch, Nina (2020): The clue is the mix. Multifunctional re-uses in former retail real estate properties. Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers: Urban Design and Planning, 173(5), 171–181. DOI: 10.1680/jurdp.20.00041.

Hangebruch, Nina and Othengrafen, Frank (2022): Resilient Inner Cities: Conditions and Examples for the Transformation of Former Department Stores in Germany. Sustainability (Switzerland), 14(14). DOI: 10.3390/su14148303.

Hannover.de (2024a): Einzelhandelsimmobilienmarkt 2021. Marktstimmung: Teils erhebliche Einbrüche, Entspannung erst langsam in Sicht. https://www.wirtschaftsfoerderung-hannover.de/de/Microsites/Immobilienmarktbericht_2021/einzelhandelsimmobilienmarkt_hannover_2021/Marktueberblick_Einzelhandel.php, accessed: 16.07.2024.

Hannover.de (2024b): Projekt `aufhof´. Zwischennutzung des ehemaligen Kaufhof-Gebäudes ab Juni. https://www.hannover.de/Leben-in-der-Region-Hannover/Politik/B%C3%BCrgerbeteiligung-Engagement/Innenstadtdialog-Hannover/Zwischenraum-Innenstadt/Zwischennutzung-des-ehemaligen-Kaufhof-Geb%C3%A4udes-ab-Juni, accessed: 06.07.2024.

Hannover.de (2024c): Rückblick. Bilanz für den aufhof als erfolgreiches Experiment. https://www.hannover.de/Service/Presse-Medien/Landeshauptstadt-Hannover/Aktuelle-Meldungen-und-Veranstaltungen/Bilanz-f%C3%BCr-den-aufhof-als-erfolgreiches-Experiment, accessed: 22.10.2024.

Helfferich, Cornelia (2011): Die Qualität qualitativer Daten. Manual für die Durchführung qualitativer Interviews. 4th edition. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Herth, Annika; Verburg, Robert and Blok, Kornelis (2024): The innovation power of living labs to enable sustainability transitions: Challenges and opportunities of on-campus initiatives. In: Creativity and Innovation Management, 2024; 0:1-16. DOI: 10.1111/caim.12649.

Imorde, Jens and Junker, Rolf (2014): Shoppen ja, aber nur nicht im Warenhaus!? In: Bundesinstitut für Bau-, Stadt- und Raumforschung (BBSR) im Bundesamt für Bauwesen und Raumordnung (BBR) (Ed.) (2014): Shoppen in der City, Informationen zur Raumentwicklung, 1: 49-54.

Klemme, Marion (2022): Transformation der Innenstädte: Zwischen Krise und Innovation. In: Information zur Raumentwicklung, Innenstädte transformieren!, 2: 4-15.

Koens, Ko; Stompff, Guido; Vervloed, Janneke; Gerritsma, Roos and Horgan, Donagh (2024): How deep is your lab? Understanding the possibilities and limitations of living labs in tourism. In: Journal of Destination Marketing and Management 32: 1-9. DOI: 10.1016/j.jdmm.2024.100893.

Landesinitiative StadtBauKultur NRW (Ed.) (2020): Neueröffnung nach Umbau Konzepte zum Umbau von Warenhäusern und Einkaufscentern.

LHH (Landeshauptstadt Hannover) (Ed.) (2016): Stadtentwicklungskonzept. "Mein Hannover 2030". https://www.hannover.de/content/download/579921/file/LHH_Broschuere_Stadtentwicklungskonzept_2016_web.pdf

LHH (Landeshauptstadt Hannover) (Ed.) (2024a): aufhof Hannover, https://www.aufhof-hannover.de/, accessed: 03.07.2024.

LHH (Landeshauptstadt Hannover) (Ed.) (2024b): Plenum: urbane Mixturen. Raumstrategien zur Transformation von Leerstand in Innenstädten, https://www.aufhof-hannover.de/event/plenum-urbane-mixturen, accessed: 03.07.2024.

LHH (Landeshauptstadt Hannover) (Ed.) (2024c): Befristete Weiterführung der Zwischennutzung "aufhof" im ehemaligen Galeria Kaufhof an der Seilwinderstraße. Drucksache Nr. 0447/2024.

Liebold, Renate and Trinczek, Rainer (2009): Experteninterview. In: Kühl, Stefan; Strodtholz, Petra and Taffertshofer, Andreas (Eds.): Handbuch Methoden der Organisationsforschung. Quantitative und Qualitative Methoden. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 32-56.

Mayring, Philipp (2010): Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse: Grundlagen und Techniken. 11th revised edition. Weinheim: Beltz Verlag.

Meuser, Michael and Nagel, Ulrike (2002): ExpertInneninterviews – Vielfach erprobt, wenig bedacht. Ein Beitrag zur qualitativen Methodendiskussion. In: Bogner, Alexander; Littig, Beate and Menz, Wolfgang (Eds.) (2002): Das Experteninterview. Theorie, Methode, Anwendung. Opladen: Leske + Budrich, 71-93.

Rieper, Andreas and Schote, Heiner (2022): Die Hamburger Innenstadt – Auf dem Weg von der Einzelhandels– und Bürocity zum multifunktionalen Quartier? In: Appel, Alexandra and Hardaker, Sina (Eds.): Innenstädte, Einzelhandel und Corona in Deutschland, 43–60.

Statista (Ed.) (2024a): Statistiken zu Kauf- und Warenhäusern in Deutschland, https://de.statista.com/themen/1649/kauf-und-warenhaeuser-in-deutschland/#statisticChapter, accessed: 18.07.2024.

Statista (Ed.) (2024b): Treibhausgasemissionen des deutschen Bauhauptgewerbes in den Jahren 2000 bis 2021, https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/476879/umfrage/treibhausgasemissionen-des-deutschen-bauhauptgewerbes/, accessed: 20.08.2024).

Statistisches Bundesamt (Ed.) (2023): Indikatoren der UN-Nachhaltigkeitsziele. https://sdg-indikatoren.de, accessed: 09.02.2023.

WBGU (Wissenschaftlicher Beirat der Bundesregierung Globale Umweltveränderungen) (Ed.) (2011): Welt im Wandel. Gesellschaftsvertrag für eine große Transformation. Berlin. Available in English: https://www.wbgu.de/en/publications/publication/ world-in-transition-a-social-contract-for-sustainability, accessed: 10.10.2024.

Wirtschaftsförderung der Landeshauptstadt Hannover (Ed.) (2024): Bilanz eines erfolgreichen "Experiments" – Aufhof schließt: "Eine neue Tür wird sich öffnen". Press release. https://www.wirtschaftsfoerderung-hannover.de/de/Pressemitteilungen/hannoverimpuls/aufhof_ende.php, accessed: 16.08.2024.

ZiA (Zentraler Immobilien Ausschuss e.V.) (Ed.) (2023): Nachnutzung von Kaufhäusern. Report. Berlin/Bonn.