- Start

- Setting the scene for urban industrial land

- Forming a research approach

- Policy overview and insights

- 1990 to 2002: A narrative for spatial constraints and growth management

- 1990 to 1997 – Direction for Industrial Land

- 1998 to 2001 – High-tech in the False Creek Flats

- 2002 to 2022: Extended Narrative: (Re-) Considering Climate Change

- 2002 to 2022 – Pursuing Sustainability

- 2012 to 2022 – Densification, Intensification and other Directions for the False Creek Flats

- 2017 to 2022 – A new Vision for the False Creek Flats

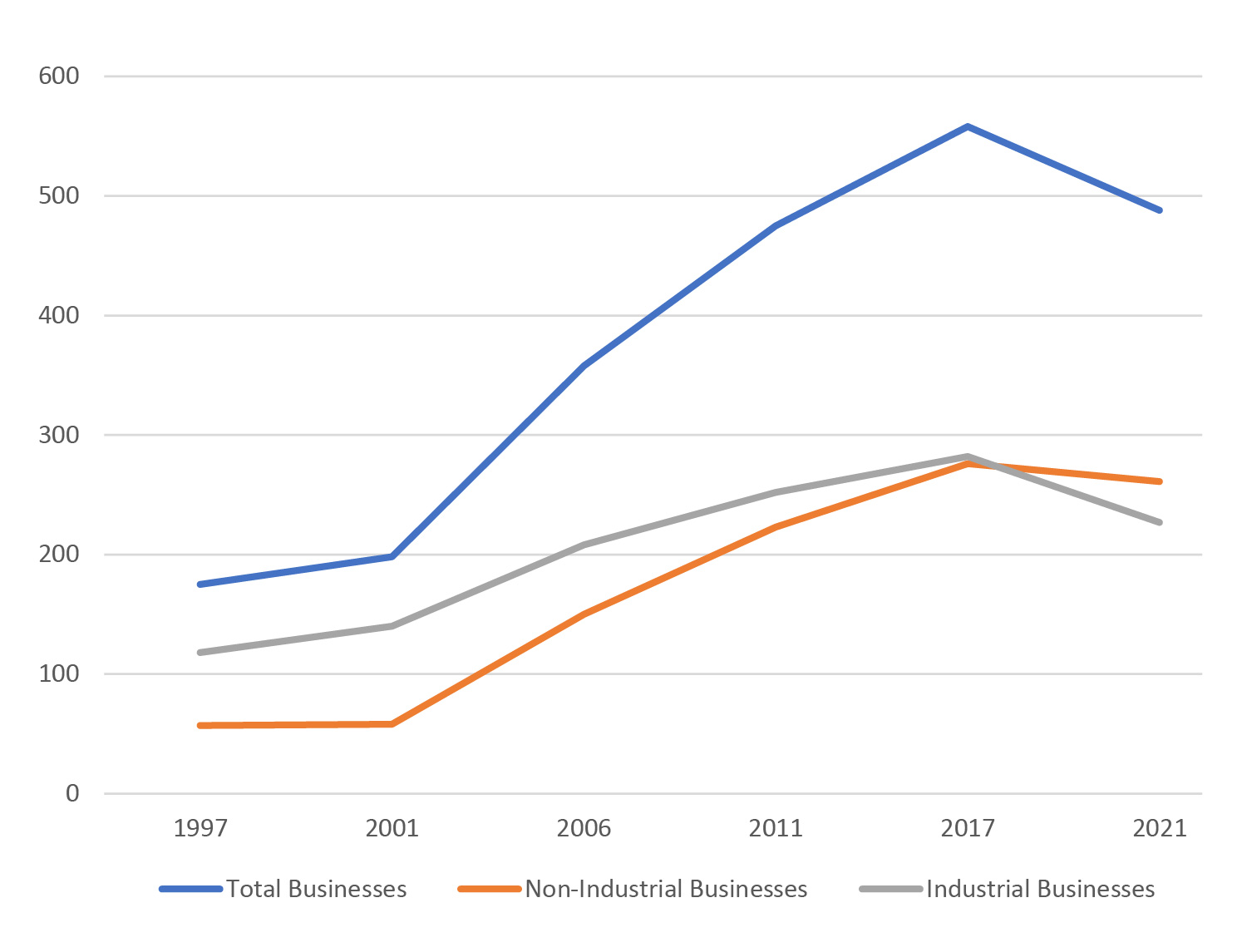

- Observed changes in business licenses data

- What can we learn from the changes observed in the False Creek Flats?

- What´s next for False Creek Flats?

- About the author(s)

- References

Published 26.04.2023

Urban Industry in Vancouver’s False Creek Flats

An Overview and Assessment of Policy Change and Impact on Industrial Lands

Keywords: Vancouver; False Creek Flats; industrial lands; policy review

Abstract:

Since the most recent 2022 IPCC World Climate report, it is more than ever evident that meeting the goals set out in the Paris agreement in 2017 requires quick and comprehensive action. Building a green economy in this context can provide a more sustainable approach to achieving economic growth within the constraints of urban areas. A closer look at Vancouver with its strong green sector growth presents a promising example for this effort. The article therefore showcases policies and their impact on developments that occurred in the recent past of the cities False Creek Flats industrial area. An area that stands out with its growing and increasingly diverse urban firm population that is facing dynamics of residential encroachment, sky-rocketing rents and a long-standing vision for a post-industrial city.

Setting the scene for urban industrial land

The United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) has provided a general roadmap with its Green Economy Report that outlines directions and recommendations for several economic sectors. These address both a reduction in the overall output of greenhouse gasses (GHG) but also champion a greater focus on social inclusiveness (UNEP 2011: 7). As these sectors and related industrial land use types provide a large share of employment, they play a key part in transitioning to a more future-proof green economy (UNEP 2011: 259–269). This perspective brings forward a renewed interest in growing these sectors within cities where they can benefit from knowledge spillovers, circular economies (ibid.), access to a large labor pool, close customer base, shorter transport routes, and other factors that enable innovation and GHG reductions (Grodach and Martin 2021: 1–4). Attempting to utilize locations in urban areas for manufacturing and similar use types is however a deviating and contested sentiment to the well-established post-industrial aims for functional separation both in and out of cities (Logue 1998: 3; Webster et al. 2014: 1). In order to better understand how to pursue such a pivot, this article examines policies for the industrially zoned areas in the city of Vancouver, which demonstrate focus and success in cultivating an increasing number of green economy businesses that contribute to the reduction of GHG and waste (by-) products (VEC 2018: 1–7, 2014: 9).

The False Creek Flats district (FCF) serves as a learning case study from which policies adopted for industrial land are analyzed for their contribution in accommodating a range of manufacturers, distributors, wholesalers and other use types that are conducive to the idea of the green economy (City of Vancouver 2015: 58; Bursey 2020: 7). Describing the contribution of these policies then serves an answer to the question: How have the city and region influenced the False Creek Flats firm population through policies? This in return offers both inspiration and an entry point for others pursuing similar outcomes for an urban industrial area.

From a German perspective, the FCF is an interesting research context since policies such as the Leipzig Charta promote comparable initiatives under the heading of the productive city (BMI 2020: 6–7); this policy articulation pursues similar goals regarding the creation of a wide span of employment opportunities in urban areas (VEC 2021: 1; BMI 2020: 1). As well, the case study is relevant to challenges induced by a strong real estate market and zoning regulations that normally inhibit a diverse range of industrial uses types despite the social contributions they can bring to urban areas (Cox 2022: 7; Bathen et al. 2019: 14). The article begins with a historical overview of the policy development for the FCF; this builds off work by Logue (1998) and highlights institutional efforts at regional and municipal levels that have guided the development of industrially zoned land (1998). Accompanied by this is a parallel evaluation of the business types present in the FCF at regular intervals throughout the last 25 years. In summation the article offers an insight into how institutional efforts on a regional and municipal level have contributed to shaping industrial lands based on firm-level activities and land use type changes observed in the case study area of the FCF.

Forming a research approach

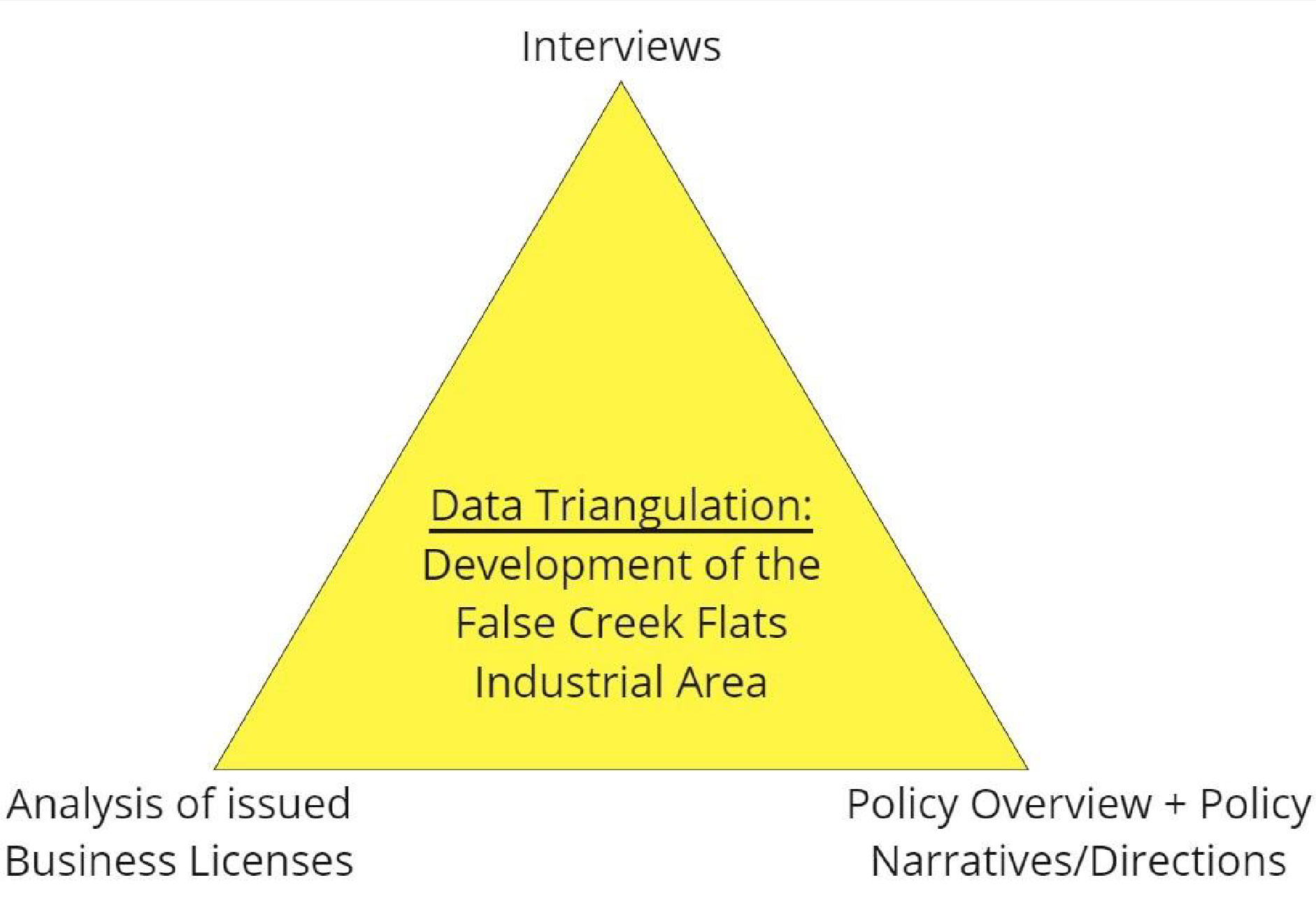

In order to provide an answer to the question posed a structured approach is used. It is formed through the selection of three methods that provide the opportunity for a data triangulation as shown in Figure 1 (Flick 2010: 281). These create three separate data sets that are then analyzed to corroborate interpretations of the data generated and to provide greater accuracy for these (ibid.: 283).

At first the narrative policy framework provides a structure for the policy overview of the FCF; this is achieved by analyzing a corpus of policy documents and their respective framework elements following Jones et al. (2014). This corpus consists of policy documents published by the city of Vancouver as well as Metro Vancouver spanning a timeline from 1990 to 2022 following definitions used by Logue (1998) as selection criteria. The overview as a result facilitates identifying the issues at hand and the policy direction for industrial land chosen by these institutions (Jones et al. 2014). Second, the policy overview is broken down into time intervals resulting in six reference years, which are compared using data based on issued and georeferenced business licenses. As such, the analysis aims to find indications that confirm the implementation and impact of specific policy directions based on the number and type of businesses present in a case study area (Reidsma et al. 2011). Finally, interview statements from local business stakeholders and policy experts help corroborate policy impact, outline current challenges, and provide other insights (Kallio et al. 2016).

Policy overview and insights

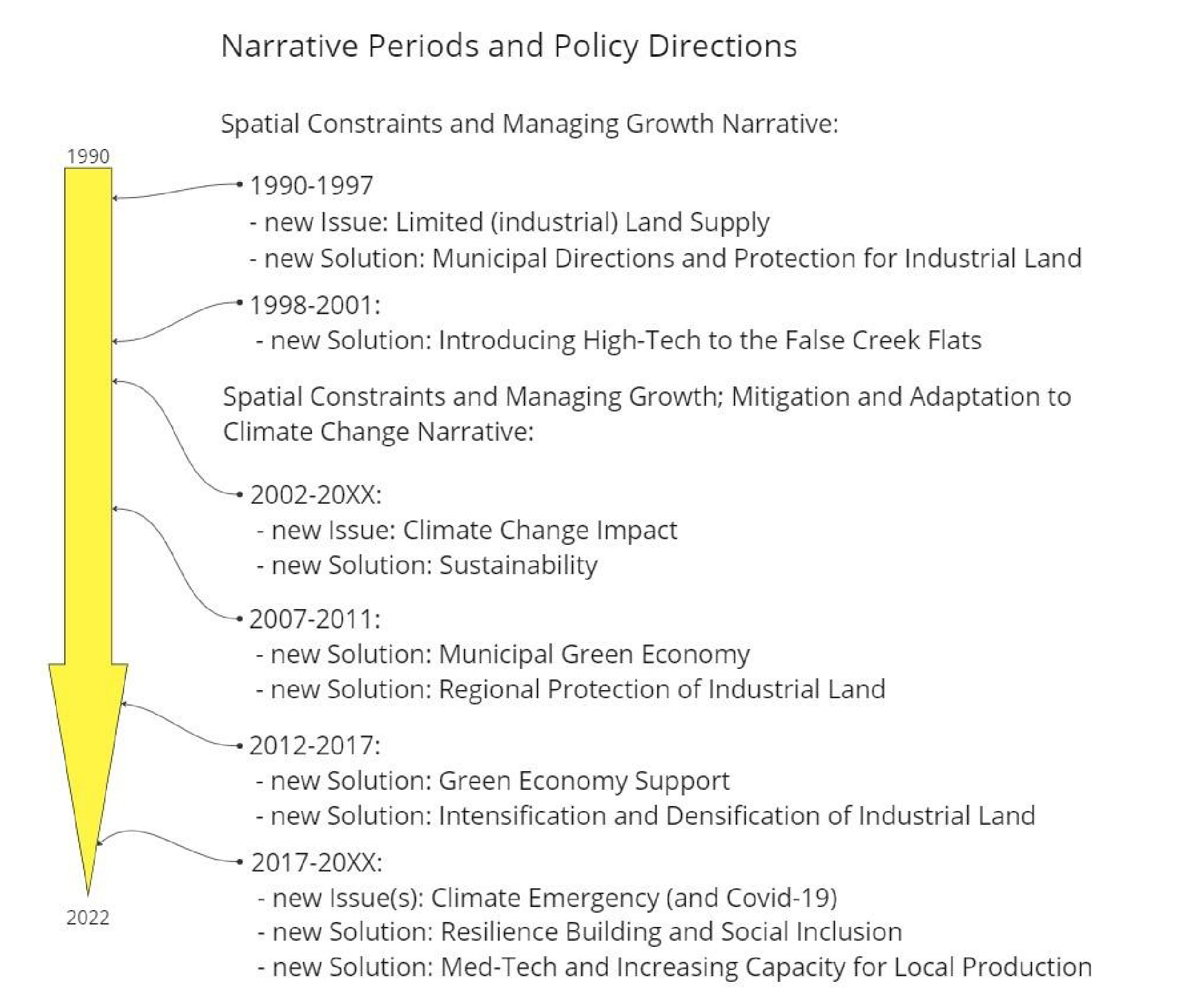

For the overview the policy directions, problem context and the overarching narratives are brought together and summarized to provide a short characterization of each period in the overview as shown in Figure 2. As a conclusion to this part the current directions for the FCF are outlined.

1990 to 2002: A narrative for spatial constraints and growth management

The first narrative in the timeline is identified based on its characteristics assigned in the narrative policy framework. According to policy documents at this time, spatial constraints within the Metro Vancouver region are priority issues (Metro Vancouver 1996: 7) that hinder potentials for urban expansion in the region (Metro Vancouver 1996: 7). This issue is exacerbated by a 70 percent growth in population that is accurately predicted to occur by 2021 (Metro Vancouver 1996: 8, 2022). Based on this problem context, policy directions are introduced with goals of balancing growth management needs and maintaining quality of life standards. We can also trace this first narrative in the timeline back to work by Logue (1998: 63), which highlights aims as early as 1974 to „ensure a post-industrial viability of the region“ through the „protection of natural and cultural amenities“ .The narrative in this context creates urgency and justifies the pursuit of a new policy direction for urban and industrial lands— a quality that is comparable to other cities (Grodach 2022: 6-7).

1990 to 1997 – Direction for Industrial Land

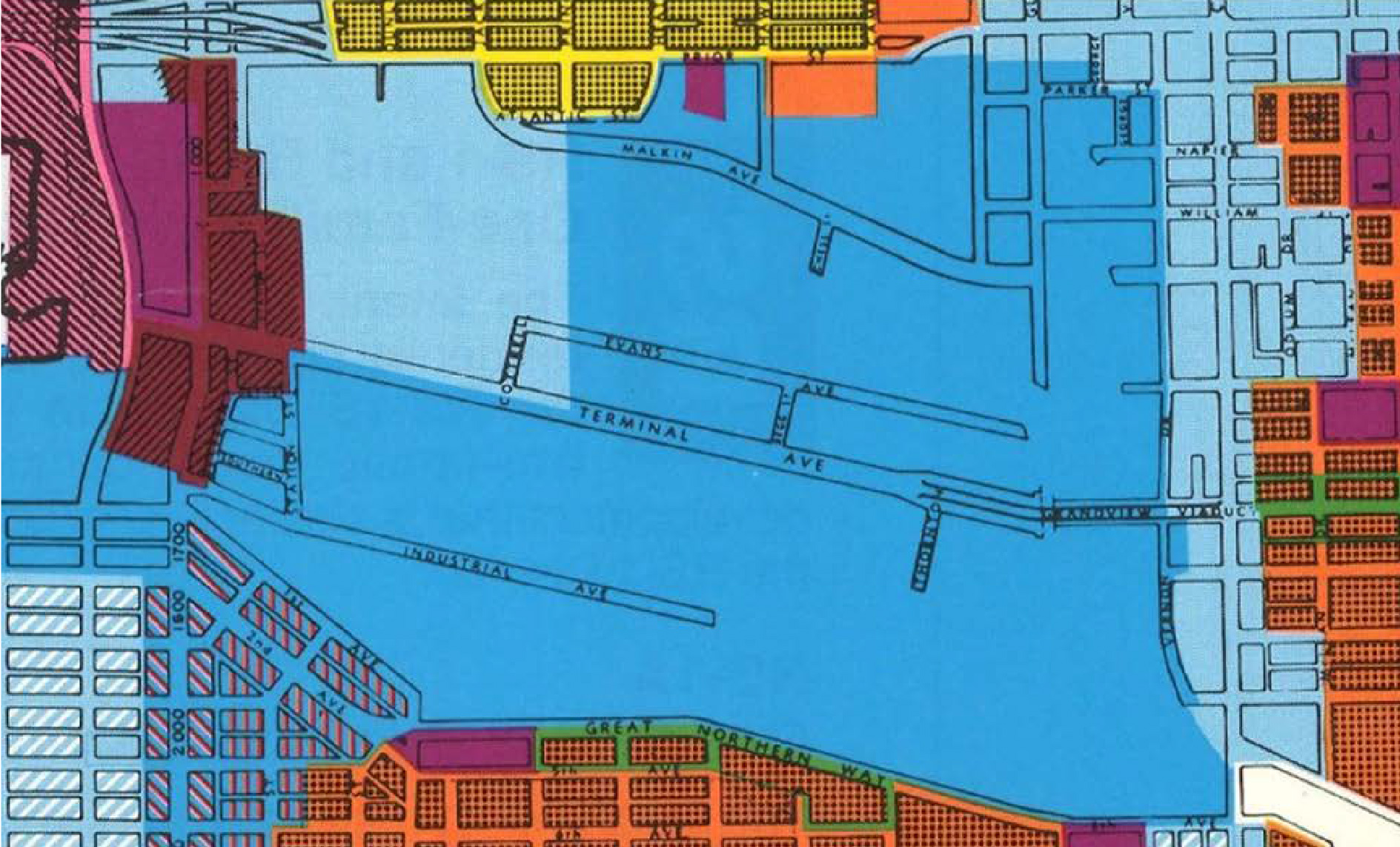

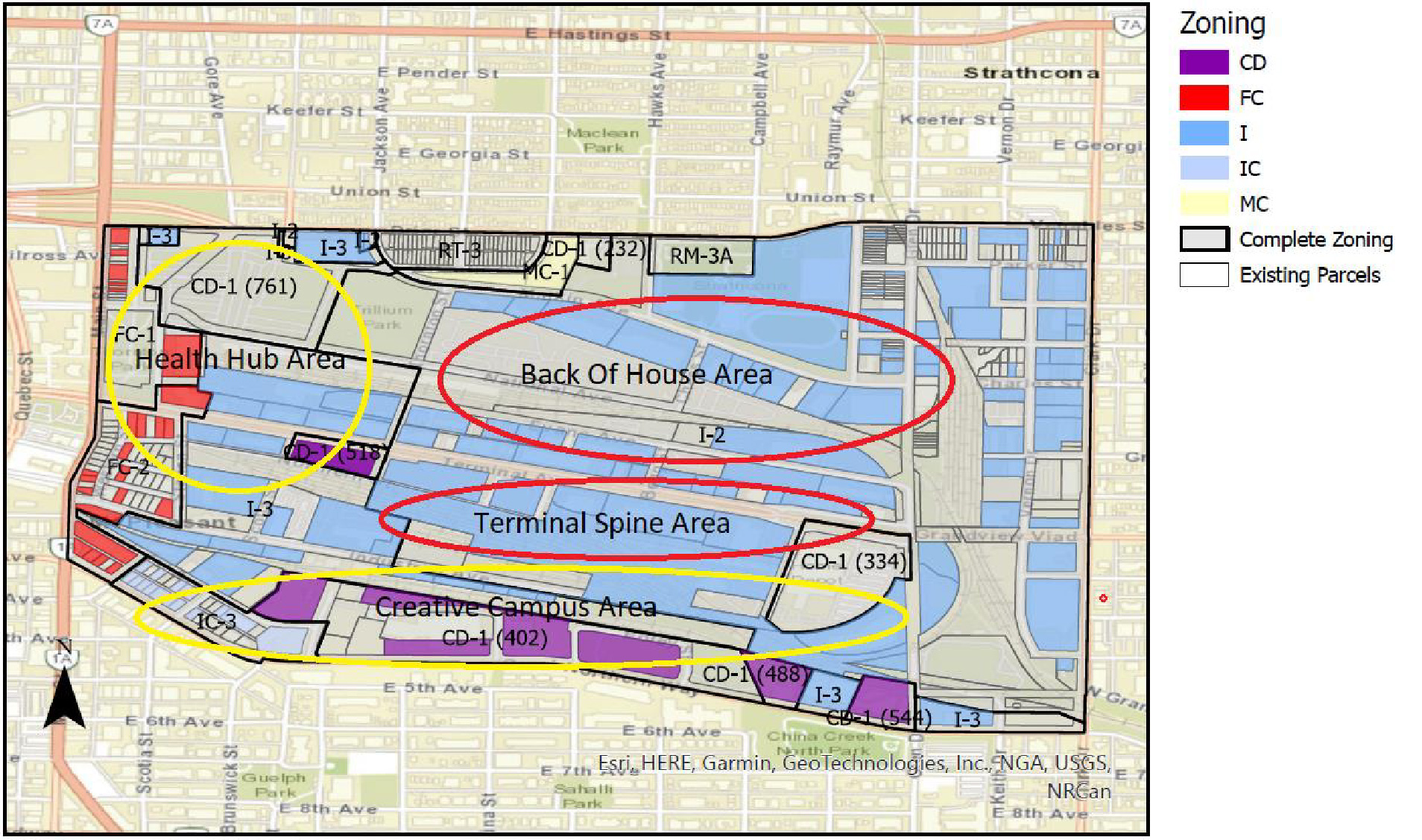

As a result of this narrative, a push for enhanced regional planning arrived in the early 1990s within the Creating Our Future program; this follows up on the fundamentals of the previously proposed 1975 Regional Plan (Metro Vancouver 1994: 10–15). Here critiques of post-industrial sentiments build momentum (Logue 1998: 77). In 1991, these sentiments are recognized by the city of Vancouver as increasingly problematic as industrial lands are gradually disappearing at the municipal level (City of Vancouver 1991: 16–17). In particular, the role of industrial lands is revaluated in the 1995 City Plan and future efforts outline moves away from the post-industrial sentiments (City of Vancouver 1995a: 31, 43, 48). What is next for industrial land in the city of Vancouver is a transformation toward becoming a location for key city-serving industry and employment opportunities needed in the future. Through this new perspective they achieve an additional value that demands a long-term protection to not continue on the trajectory of their displacement, which is realized through the 1995 Industrial Lands Policies (City of Vancouver 1995c: 1–4). Pressures from housing demands remain, however, at both municipal and regional level. A new policy direction for industrial land emerges to facilitate industrial uses that are more conducive to be included in an increasingly dense urban landscape (Metro Vancouver 1994: 13, 1996: 25). As a result, a number industrial areas in the City of Vancouver are being delineated in the cities’ Industrial Lands Policies with a focus on specific types of industrial uses such as distribution related or city-serving industrial uses (City of Vancouver 1995c: 1–4). Among this list of future industry areas are the FCFs’ industrial zones as shown in blue in Figure 3 for which provisions demand a forward-looking planning program to include city-serving and future-proof, clean, industrial uses; these could be more compatible with the mixed and residential developments that are gradually enclosing the area as shown in yellow, reddish and orange in Figure 3 (City of Vancouver 1995c, 1995b).

This new policy direction appears to be a response to the changes already occurring since the 1980s following which the cities firm population is characterized by an ongoing trend of heavy industrial uses leaving urban areas, which is also the case in the FCF as pointed out in the Preliminary Concept Plan for the area (City of Vancouver 1995b). With the last few heavy industrial companies expected to leave the FCF in the late 1990s, light industrial uses increasingly took up the newly vacant properties and structures that are at that point making up the majority of the firm population (ibid.). As a result of this development, the area was mostly rezoned from a heavy industrial M-2 zoning to a light industrial I-2 zoning in 1996 to match this new reality (ibid.). The rezoning closed a long chapter of the FCF heavy industrial history with its early aim to accommodate a new western terminus for the Canadian rail network by infilling the easternmost part of the False Creek waterway (Donald Luxton and Associates Inc. 2013: 32, 45, 69). The legacy of which remains through the rail infrastructure still in place that was the reason why the area was ascribed with a status of low residential amenity in the 1991 Central Area Plan and incidentally protected from residential encroachment (City of Vancouver 1991: 16–17). To this day, this status maintains and is corroborated with statements from a business stakeholder in the area.

1998 to 2001 – High-tech in the False Creek Flats

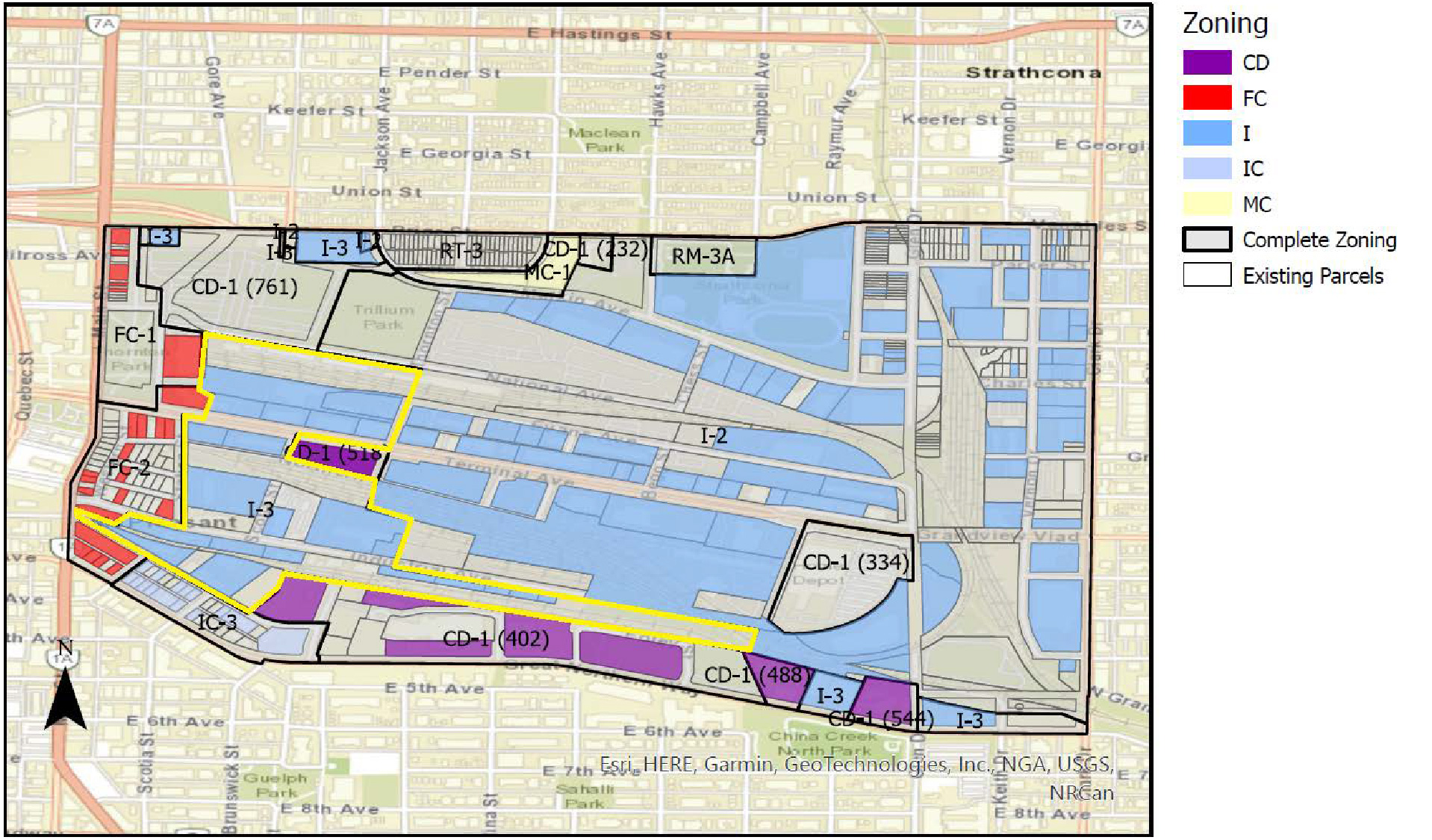

The Industrial Lands Policy following its adoption in 1995 (City of Vancouver 1995c) furthermore provides the groundwork for a refinement of the clean industry policy direction for the FCF that is respectively introduced and pushed on a municipal level by the 1996 Preliminary Concept Plan and the following 2001 Urban Structure Plan (City of Vancouver 2001: 3, 1995b). The refinement in the policy language focuses on the rezoning of the westerly I-2 area (hosting high-tech businesses) to an I-3 area in 1999 as shown in Figure 4 (City of Vancouver 2001: 3, 2009: 1–3).

As a result of the regulatory adjustment high-tech uses are promoted through floor-space-ratio bonuses (City of Vancouver 2001: 7). In parallel, the I-3 area functions as a buffer between the light industrial and the more emission prone mixed commercial area of the FCF (see Figure 3). Despite the separation from the I-2 zone to the east and better access to public transit, the new I-3 zone was not as an effective tool for attracting high-tech businesses as anticipated (City of Vancouver 2007: 27). This likely led to an additional adjustment in 2009 leading to the outright approval of the general office use type to meet the demand at the time for office space close to the Downtown core just west of the FCF (City of Vancouver 2009: 1–3). In this context some speculate that the introduction of a competing and higher value use type (office uses) can catalyze an increase in property values for industrial lands (Ohls et al. 1973: 1–3). Consequentially, industrial users are prone to being priced out in the long-term. The zoning regulation therefore mandates for one out of three floors to permit a compatible light industrial use (City of Vancouver 2022a, 2017c). With this, the I-3 zoning regulations adjust the floor-space-ratio upward incentivizing higher density and light industry uses (City of Vancouver 2022a). Comparing this policy direction with Grodach’s work on industrial land in San Francisco parallels become apparent in the endeavor of attracting high-tech businesses and protecting industrial land for cleaner uses. Another parallel between the two cities is the Live/ Work policy direction that made its way into the early 1996 Preliminary Concept Plan for the FCF. The Live/Work idea aims to facilitate artist studios and create a corresponding zoning use type on I-2 industrial land for an increasingly valued creative economy.

2002 to 2022: Extended Narrative: (Re-) Considering Climate Change

Moving back to the early 2000s, the change in direction toward more high-tech office uses is accompanied by changes to the initial narrative along with an evolving problem context. The problem context no longer entirely concentrates on population growth and spatial constraints but extends to concerns of climate change (Metro Vancouver 2010: 8–11). While the early 1990 Clouds of Change report leverages this problem context to introduce goals that are headlined with the slogan “climate change means we have to change“ (City of Vancouver 1990: 1–4), the comprehensive efforts to methodically address the problem on both municipal and regional scale are picked up much later. This lag and push to address climate change following the 1990 Cloud of Change reports consists of a policy bundle including the initial 2004 Climate Friendly-City plan (City of Vancouver 2004), the 2004 Food Action Plan addressing impacts on agriculture (City of Vancouver 2013), the 2005 Green Building Strategy (City of Vancouver 2005a) and the 2005 Community Climate Change Action Plan (City of Vancouver 2005b).

2002 to 2022 – Pursuing Sustainability

Building on the addition of the climate change problem context, the 2002 Sustainable Region Initiative introduces sustainability as a concept and policy direction to address climate change (Metro Vancouver 2010: 8–11). From then on, climate change mitigation and adaptation are included in regional planning efforts and later on part of the 2008 Sustainability Framework. The framework outlines aspects of the region’s service provision and includes sustainability aims that relate to industrially zoned land (ibid.). This intertwines with policy efforts on the municipal level towards green economic development that are sowed in the city’s 2005 Green Building Strategy (City of Vancouver 2005a) and the 2006 Vancouver Economic Commission’s Guiding Principles. The latter of which plots a course for the city to become a global leader in sustainability practices and outlines efforts to draw in green technology businesses (City of Vancouver 2006: 1, 6). The guiding principles also emphasize that the Vancouver Economic Commission is to act as a conduit between public and private efforts toward this end (ibid.). The FCF at this point are maintaining their city-serving function that is reformulated and sharpened in 2007 to a production, distribution and repair designation (PDR) (Grodach 2022; City of Vancouver 2007: 27). With the 2012 Greenest City Action Plan (GCAP) and the Vancouver Economic Commission’s Economic Action Strategy in 2011 this PDR designation is complemented by goals for the area to become a green business hub (VEC 2011; City of Vancouver 2012).

2012 to 2022 – Densification, Intensification and other Directions for the False Creek Flats

Coinciding with the ambitious goals for a green economy is a dwindling supply of industrial land. Regionally, the supply of industrial land is expected to reach a critical point somewhere between the mid-2020s (Site Economics Ltd. 2015: 63–65) and 2030 (Gilmore 2015: 2). Without a suitable supply of industrial land, the growth of the regions light and heavy industries is therefore limited. At the same time the lack of supply drives up the industrial land price worsening market pressure that is already putting into question the viability of existing businesses on industrial land (VEC 2017). Considering the issue of outdated and dilapidated building stock that still is available, the situation looks to be highly problematic (HESSEY Consulting + Architecture 2021).

Logue (1998: 30–31, 79–80) in his work has been hinting at this very issue being exacerbated through the on and off redevelopment of industrial land in favor of residential projects over the past decades. With the time period reviewed for this work concluding in 1990 this future problem also made its way into the 1991 Area Plan and is further addressed with the following 1995 Industrial Lands Policies and the regional 2011 Regional Growth Strategy (City of Vancouver 1991, 1995c; Metro Vancouver 2011). These policies promote the protection of the remaining industrial land supply with direction at municipal and later at the regional level. The policy direction resulting from this issue is the intensification (increasing number of jobs on a given piece of land) and densification (increasing usable space) of industrial land which is sharpened through the 2014 Industrial Land Protection and Intensification Policies (Metro Vancouver 2014) which culminate in the 2021 Industrial Lands Strategy (Metro Vancouver 2021), while the 2017 M- and I-Districts Bulletin acts as a municipal effort to pursue this on industrial land (City of Vancouver 2017a).

2017 to 2022 – A new Vision for the False Creek Flats

The policy directions outlined through the policy overview ranging from 1990 to 2022, are picked up in the 2017 Area Plan that assigns these to corresponding sub-districts (Figure 5) within the FCF.

The health hub as shown in figure 5 introduces a med-tech sub-district and new policy direction or for the area centered around the New St. Paul’s Hospital development in the Comprehensive Development zone (CD) 761 (City of Vancouver 2017b: 29, 2022a). The creative campus on the other hand is designed around the Great Northern Way CD 402. In these roles their aim is to modernize the district and intensify and diversify job capacity consisting of med-tech and creative economy uses in the former and education, high-tech and creative manufacturing uses in the latter (City of Vancouver 2017b). The back-of-house and terminal spine area are two additional components of the new vision that are planned to accommodate the densified industrial uses that complement the areas to the west with city-serving and food related PDR functionality. Another key aspect of the 2017 Area Plan as a whole is that it proposes rezonings and adjustments to zoning schedules to facilitate the densification and intensification to accommodate an increasing number of businesses and jobs. These efforts are meant to enable the FCF to accommodate another 400 businesses and 20000 additional jobs by 2041 (City of Vancouver 2017b: 145).

Observed changes in business licenses data

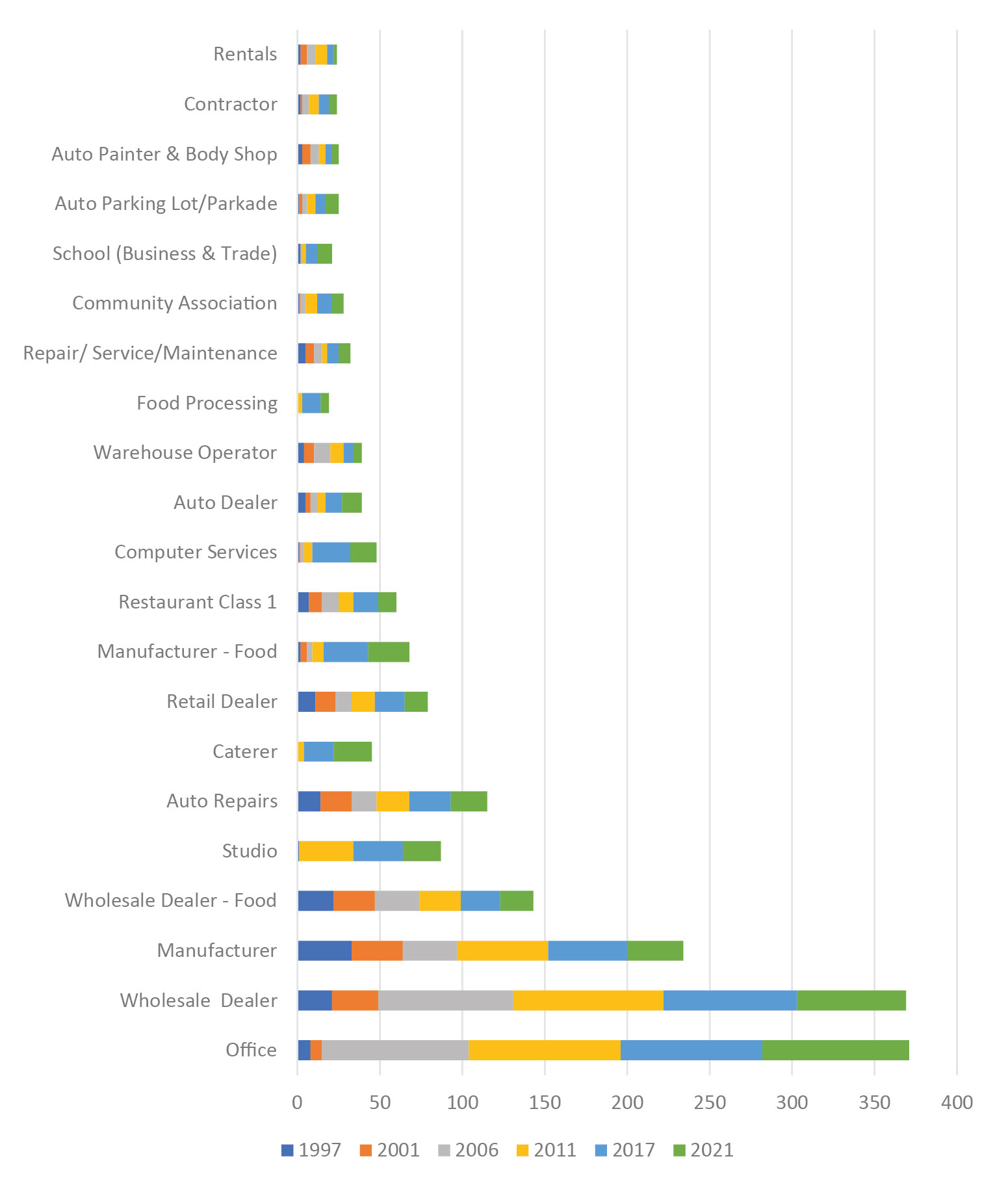

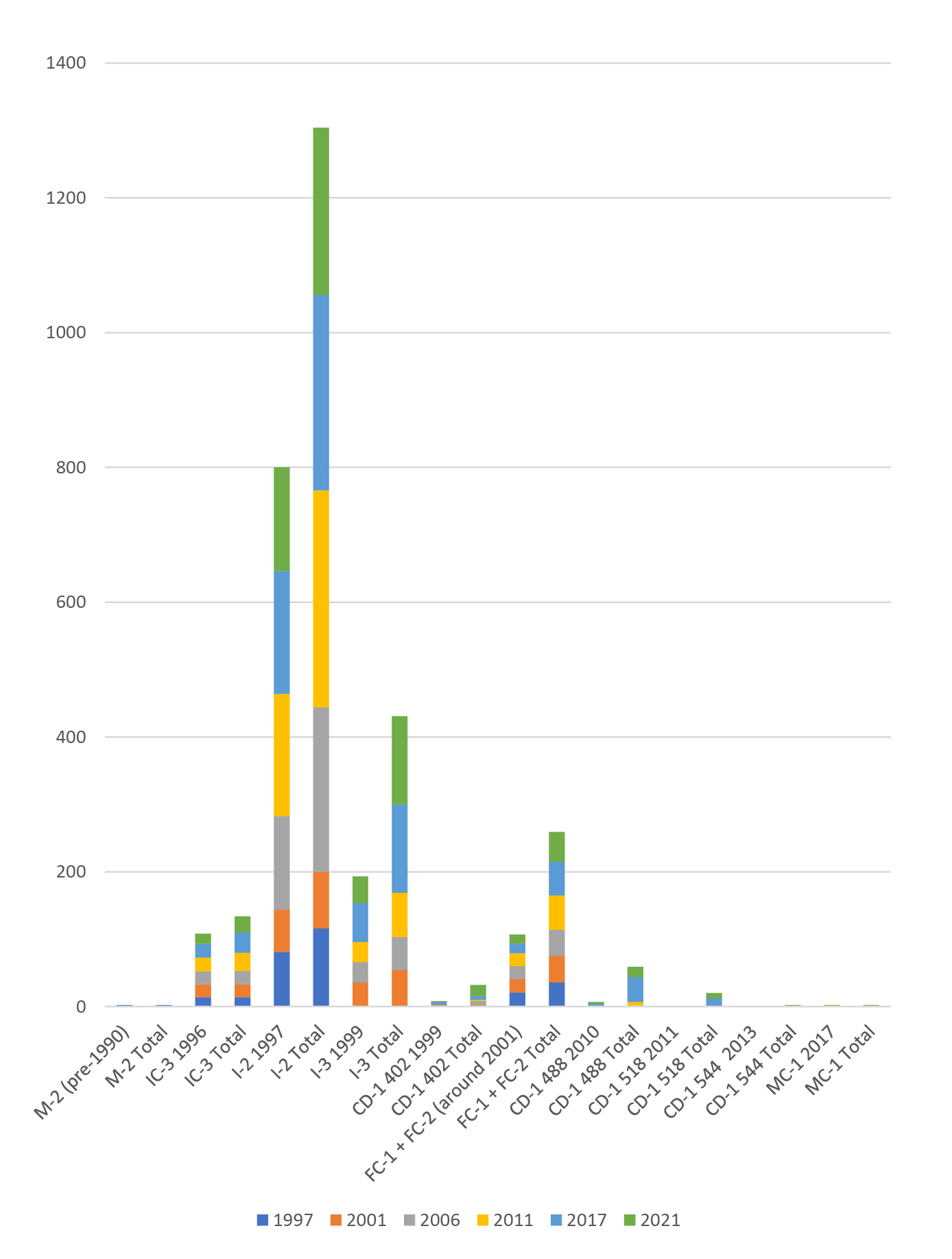

As we shift the view from policy development to firm development on the ground the influence of the directions identified in the policy overview becomes evident. Beginning with the early 2000s high-tech policy direction for the FCF the firm population analysis shows that the major increase in the number of office use types from seven to 89 in the FCF occurred between 2001 and 2006 (Figure 6 and 7). A change that can be attributed at least in part to the previously outlined rezonings and adjustments by the city.

In addition to the high-tech policy direction, the influx of artist studios can be tracked to as early as 2011 as shown in Figure 6 and 7 (City of Vancouver 2023). A potential explanation for the in comparison slow uptake of this policy direction in the FCF could be attributed to the fact that the city’s Culture Plan was not adopted until 2008 (City of Vancouver 2008). The plan emphasized support and investment for the creative economy, which would explain the following increase of the artist studio use type (City of Vancouver 2008: 4). Stakeholders interviewed confirm this support from the city’s efforts as largely successful.

Following between 2011 and 2017, the consistent efforts to accommodate and attract green economy businesses correlate with an increase in food manufacturers and other food related businesses as shown in Figure 6 and 7. These are explicitly located in the city's green economy local food sub-sector, which in 2010 is already the largest of its kind by number of green jobs, followed by the clean-tech and green buildings sub-sectors (VEC 2014: 47). During an interview with a business stakeholder contributing to gastronomy activities, policies like the GCAP were highlighted as key for facilitating food industry activities. This indicates and is substantiated by the data gathered by the VEC on the increase in green jobs, that specific sector developments are not entirely market phenomena, but also in part a result of integrated policy and funding development like GCAP Phase 1 and Phase 2 in 2015.

This breakdown of business licenses by use type (Figure 6) and by number (Figure 7) can also be correlated with the rezonings from I-3 to FC-1, FC-2, MC-1 and CD-761 (City of Vancouver 2022a, b, c, d, e). According to the interviewed business stakeholders, these neighboring zones are considered problematic as these four permit non-industrial and residential uses; moreover, these uses are not compatible with light industrial uses. Because of this issue, the CD 761 zoning schedule in particular presents efforts to spatially buffer the residential and hotel type uses from light industrial uses in the FCF (City of Vancouver 2022e). However, the pertinent issue arising through the CD 761 hospital development and med-tech policy direction is the expected increase in demand for additional housing for hospital staff. In this fashion, the CD alongside the FC-1, FC-2, MC-1 zones contribute to pressure from non-industrial uses in the area.

These introductions of new policy directions align with the areas overall changing industrial firm population. The industrial firm population is a selection of use types within the issued business license database based on the 2018 Metro Vancouver definition of “traditional industrial uses” (Metro Vancouver 2018: 3). This selection of use types shows that as a whole the share of these traditional industrial uses dropped from 70 percent of all businesses in the FCF in 2001 to 58 percent in 2006. This downward trend continues to a 50 percent share of industrial uses in the 2021 reference year (Figure 9).

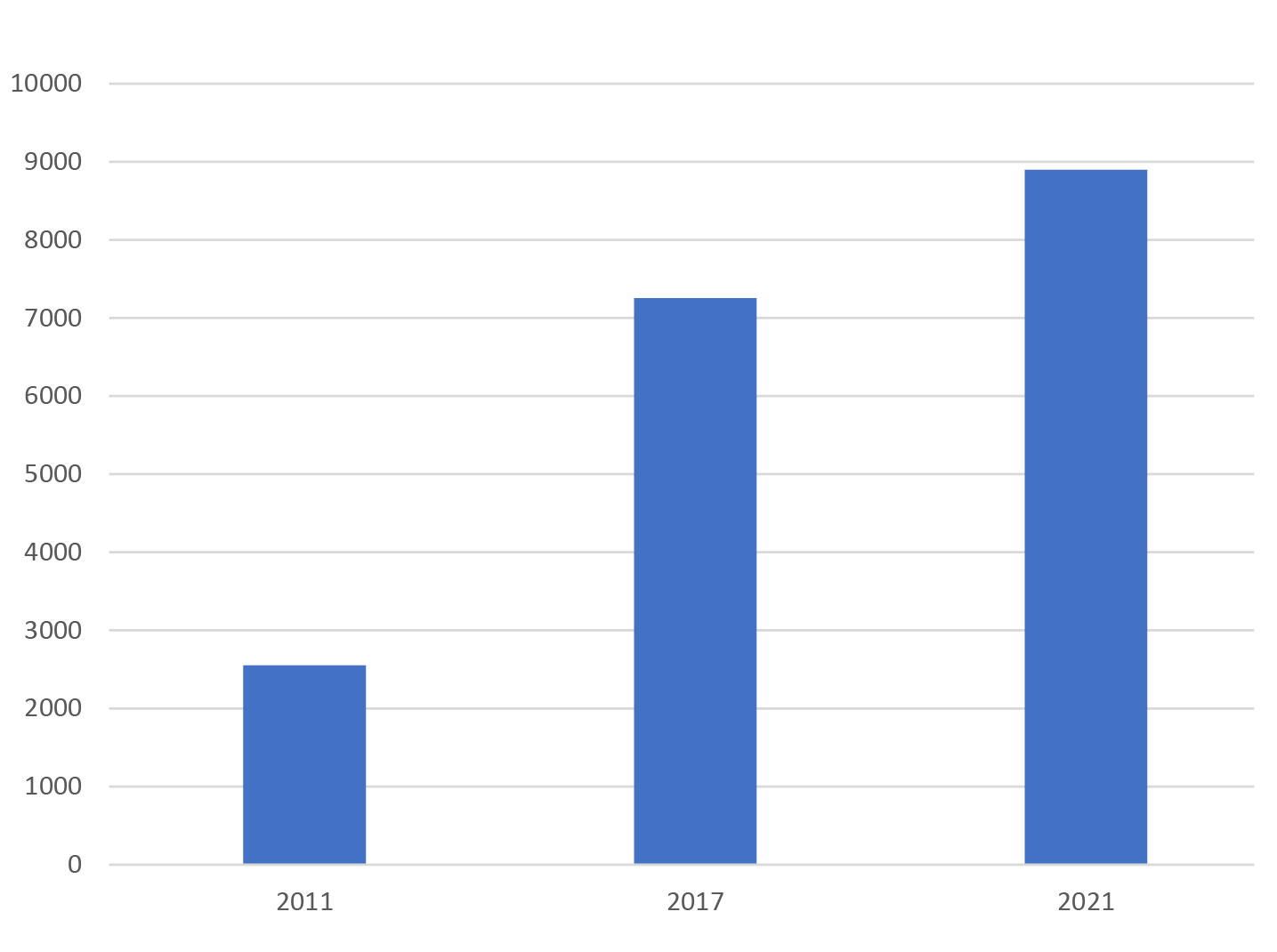

The analysis of the business license data however also shows that an intensification has been taking place since 1997 as traditional industrial use types in the area grew in number from 118 to 282 by 2017, while the total number of businesses increased from 175 to 558, followed by a drop-off in 2021 (Figure 9). In addition the number of employees in the area grew significantly from 2551 in 2011 to 8894 in 2021, which matches this intensification process (see Figure 8). These developments show that the number of non-industrial, traditional industrial uses and employment increased in parallel to the rezoning processes that occurred over the time period as shown in the District Schedule timeline in Figure 7.

With respect to densification and intensification, interviews also revealed that challenges remain for continued growth such as the lag in required regulatory adjustments regarding the permitted uses on a zoning level and the permitted uses or use allowance within specific structures. Among other regulatory requirements a relaxation of these is needed for the continued co-location of business types and activities that are compatible or complementary on densified and intensified industrial land. The data in Figure 7 also shows that many de-facto non-traditional industrial uses made their way even into the I-2 zone in each reference year. Therefore, future development and regulatory adjustments need to move toward concentrating those uses that are actually presenting an emission related compatibility issue on industrial land, while relocating those that do not into non-industrial areas to make available spaces for key industrial uses.

What can we learn from the changes observed in the False Creek Flats?

In response to the guiding question How have the city and region influenced the False Creek Flats firm population through policies? the policy overview has shown that the narrative founded on the problem context of spatial limitations has not drastically changed. Rather, it has evolved since 1990 and to this day is used to introduce new policy directions. These in addition pursue the narratives underlying goal to maintain or enhance the quality of life in the region to continue to attract new talent and businesses. Some policy directions and responses to the problem contexts present tensions with one another that in the FCF are solved through spatial separation into so-called hubs. These policy directions are also evident in the more specific changes in the areas firm population, expressed through analyses of issued business licenses; these can also be correlated to rezonings to show comparable patterns. The increase of non-industrial uses and coinciding introduction of new policy directions ultimately points to a gentrification of traditional industrial business types. Yet at the same time, the concurrent presence of traditional industrial use types speaks to how the adoption of well-articulated policies is effective in protecting their presence. Whether the city can continue down this path in combination with the intended efforts for densification and intensification of the FCF remains to be seen.

What´s next for False Creek Flats?

The city of Vancouver has the opportunity to continue to build an ecosystem for research and manufacturing in the FCF. This ecosystem can push collaboration, create and opportunities education, training or (public-private) partnerships with innovative businesses and other stakeholders. Indeed, these features and diversity of economic, cultural and social activities provide the foundation and capacity for innovation in the green economy.

What this research has attempted to do is to outline how the FCF has changed in accordance with the identified narratives and associated policy directions based on the businesses in the area. This notwithstanding, there are weakness in the delineation of industrial and non-industrial use types for the industrial firm population selection. Weaknesses also remain due to the required simplification of regional and municipal policy efforts to form individual policy directions and the simplification of their timeline of implementation for the purposes of evaluation.

Upon which future research needs to continue to identify ways to protect the lands that support a green economy and to improve on evaluating and thereby qualifying industrial land policies.

Recommendations include focusing on the FCF and efforts to intensify and densify industrial lands. This approach however needs to ensure affordability of industrial space to not undermine and limit the wide variety of functions it is meant to serve.

References

Bathen, Annette; Bunsen, Jan; Gärtner, Stefan; Meyer, Kerstin; Lindner, Alexandra; Sophia, Schambelon; Schonlau and Westhoff, Sarah (2019): Handbuch Urbane Produktion. https:// urbaneproduktion.ruhr/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Handbuch-Urbane-Produktion_2019_ Web.pdf, accessed 13.03.2023.

Bursey, Anika (2020): Mapping the GrIID. https://sustain.ubc.ca/sites/default/files/2020-096_ Mapping%20the%20GrIID_Bursey.pdf, accessed 13.03.2023.

BMI (Bundesministerium des Innern und für Heimat) (2020): Neue Leipzig Charta. https://www. bmwsb.bund.de/SharedDocs/downloads/Webs/BMWSB/DE/veroeffentlichungen/wohnen/ neue-leipzig-charta-2020.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=2, accessed 22.03.2023.

City of Vancouver (1990): Clouds of Change. Final Report of the City of Vancouver Task Force on Atmospheric Change. https://a100.gov.bc.ca/pub/eirs/viewDocumentDetail.do?fromStatic=true&repository=EPD&documentId=4367, accessed 21.03.2023.

City of Vancouver (1991): Central Area Plan: Goals and Land Use Policy. https://vancouver.ca/files/ cov/central-area-plan-goals-and-land-use-policy-1991.pdf, accessed 13.03.2023.

City of Vancouver (1995a): CityPlan. https://guidelines.vancouver.ca/policy-plan-cityplan.pdf, accessed 21.03.2023.

City of Vancouver (1995b): False Creek Flats Preliminary Concept Plan. https://council.vancouver. ca/960528/ub1i.htm, accessed 03.11.2022.

City of Vancouver (1995c): Industrial Lands Policies. https://guidelines.vancouver.ca/policy-industrial-lands.pdf, accessed 21.03.2023.

City of Vancouver (2001): False Creek Flats - Urban Structure Plan. https://council.vancouver. ca/010327/tt2.htm, accessed 21.03.2023.

City of Vancouver (2004): The Climate-Friendly City. A Corporate Climate Change Action Plan for the City of Vancouver. https://vancouver.ca/files/cov/corp_climatechangeAP.pdf, accessed 21.03.2023.

City of Vancouver (2005a): POLICY REPORT - Vancouver‘s Community Climate Change Action Plan. https://council.vancouver.ca/20050329/rr1b-complete.pdf, accessed 21.03.2023.

City of Vancouver (2005b): Green Building Strategy. https://council.vancouver.ca/20051103/ documents/pe5.pdf, accessed 21.03.2023.

City of Vancouver (2006): Vancouver Economic Development Commission - „Guiding Principles“. https://council.vancouver.ca/20060711/documents/motionb1.pdf, accessed 21.03.2023.

City of Vancouver (2007): Policy: Metro Core Jobs and Economy Land Use Plan. https://guidelines.vancouver.ca/policy-plan-metro-core-jobs-economy-land-use.pdf, accessed 21.03.2023.

City of Vancouver (2008): A new Culture Plan for Vancouver: 2008-2018. https://council.vancouver.ca/20080129/documents/rr1.pdf, accessed 21.03.2023.

City of Vancouver (2009): Rezoning Policy for „High Tech“ Sites in the False Creek Flats. https://vancouver.ca/docs/eastern-core/rezoning-policies.pdf, accessed 21.03.2023.

City of Vancouver (2012): Greenest City 2020 Action Plan - the City‘s Sustainability Plan. https://vancouver.ca/files/cov/greenest-city-action-plan.pdf, accessed 21.03.2023.

City of Vancouver (2013): Vancouver Food Strategy. https://vancouver.ca/files/cov/vancouver-food-strategy-final.PDF, accessed 21.03.2023.

City of Vancouver (2015): Greenest City 2020 Action Plan Part Two: 2015-2020. https://vancouver.ca/files/cov/greenest-city-2020-action-plan-2015-2020.pdf, accessed 21.03.2023.

City of Vancouver (2017a): Bulletin: M and I Districts - Functional Industrial Space. https://bylaws.vancouver.ca/bulletin/bulletin-m-i-districts-functional-industrial-space.pdf, accessed 21.03.2023.

City of Vancouver (2017b): False Creek Flats Area Plan. https://vancouver.ca/images/web/policy-plan-false-creek-flats.pdf, accessed 21.03.2023.

City of Vancouver (2017c): Guidelines: I-2 and I-3 - False Creek Flats. https://guidelines.vancouver.ca/guidelines-i-2-3-false-creek-flats.pdf, accessed 21.03.2023.

City of Vancouver (2022a): Zoning and Development By-law: I-3 District Schedule. https://bylaws.vancouver.ca/zoning/zoning-by-law-district-schedule-i-3.pdf, accessed 21.03.2023.

City of Vancouver (2022b): Zoning and Development By-law: MC-1 and MC-2 Districts Schedule. https://bylaws.vancouver.ca/zoning/zoning-by-law-district-schedule-mc-1-2.pdf, accessed 21.03.2023.

City of Vancouver (2022c): Zoning and Development By-law: FC-1 District Schedule (East False Creek). https://bylaws.vancouver.ca/zoning/zoning-by-law-district-schedule-fc-1.pdf, accessed 21.03.2023.

City of Vancouver (2022d): Zoning and Development By-law: FC-2 District Schedule (False Creek Flats Innovation District). https://bylaws.vancouver.ca/zoning/zoning-by-law-district-schedule-fc-2.pdf, accessed 21.03.2023.

City of Vancouver (2022e): CD-1 (761): 1002 Station Street and 250-310 Prior Street. https://cd1-bylaws.vancouver.ca/cd-1(761).pdf, accessed 21.03.2023.

City of Vancouver (2023): Home — City of Vancouver Open Data Portal. https://opendata.vancouver.ca/pages/home/, accessed 23.02.2023.

City of Vancouver Archives (2022): 1990 Zoning map : City of Vancouver, British Columbia - City of Vancouver Archives. https://searcharchives.vancouver.ca/zoning-map-city-of-vancouver-british-columbia-4, accessed 25.11.2022.

Cox, Wendell (2022): Demographia International Housing Affordability, 2022 Edition. https://urbanreforminstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Demographia-International-Housing-Affordability-2022-Edition.pdf, accessed 23.02.2023.

Donald Luxton and Associates Inc. (2013): Eastern Core (False Creek Flats) Statement of Significance.

Flick, Uwe (2010): Triangulation. In: G. Mey K. Mruck (Ed.): Handbuch Qualitative Forschung in der Psychologie. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 278–289.

Gilmore, Ryan (2015): Industrial Land Intensification: What is it and how can it be measured? https://mspace.lib.umanitoba.ca/xmlui/handle/1993/30746, accessed 22.03.2023.

Grodach, Carl (2022): The institutional dynamics of land use planning: Urban industrial lands in San Francisco. In: Journal of the American Planning Association 4/2022, 537–549.

Grodach, Carl and Martin, Declan (2021): Zoning in on urban manufacturing: industry location and change among low-tech, high-touch industries in Melbourne, Australia. In: Urban Geography 42 (4): 458–480. DOI: 10.1080/02723638.2020.1723329.

HESSEY Consulting + Architecture (2021): Activate DTES & The Flats. https://hessey.ca/hessey-vancouver-consulting-architecture-category-projects/activate-dtes-flats/, last updated 15.04.2022, accessed 31.08.2022.

Jones, Michael D.; McBeth, Mark K. and Shanahan, Elizabeth A. (2014): Introducing the Narrative Policy Framework. In: Jones, Michael D.; Shanahan, Elizabeth A. and McBeth, Mark K. (Ed.): The Science of Stories: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kallio, Hanna; Pietilä, Anna-Maija; Johnson, Martin and Kangasniemi, Mari (2016): Systematic methodological review: developing a framework for a qualitative semi-structured interview guide. In: Journal of advanced nursing 72 (12): 2954–2965. DOI: 10.1111/jan.13031.

Logue, Scott (1998): The City of Vancouver’s industrial land use planning in a context of economic restructuring. https://open.library.ubc.ca/soa/cIRcle/collections/ubctheses/831/items/1.0088463, accessed 22.03.2023.

Metro Vancouver (1994): Creating Our Future 1990. http://www.metrovancouver.org/about/library/HarryLashLibraryPublications/Creating-Our-Future-1994.pdf, accessed 22.03.2023.

Metro Vancouver (1996): Livable Region Strategic Plan. http://www.metrovancouver.org/services/regional-planning/PlanningPublications/LRSP.pdf, accessed 22.03.2023.

Metro Vancouver (2010): Sustainability Framework. http://www.metrovancouver.org/about/aboutuspublications/MV-SustainabilityFramework.pdf, accessed 22.03.2023.

Metro Vancouver (2011): Metro Vancouver Regional Growth Strategy (Metro Vancouver 2040: Shaping Our Future). http://www.metrovancouver.org/services/regional-planning/PlanningPublications/RGSAdoptedbyGVRDBoard.pdf, accessed 22.03.2023.

Metro Vancouver (2014): Metro Vancouver Industrial Land Protection and Intensification Policies. http://www.metrovancouver.org/services/regional-planning/PlanningPublications/ImplementationGuideline5–MetroVancouverIndustrialLandProtectionIntensificationPolicies-2014.pdf, accessed 22.03.2023.

Metro Vancouver (2018): Defining Industrial for the Regional Industrial Lands Strategy. http://www.metrovancouver.org/services/regional-planning/PlanningPublications/DefiningIndustrialfortheRegionalIndustrialLandsStrategy-Sep2018.pdf, accessed 22.03.2023.

Metro Vancouver (2021): Metro Vancouver Regional Industrial Lands Strategy. http://www.metrovancouver.org/services/regional-planning/PlanningPublications/Regional_Industrial_Lands_Strategy_Report.pdf, accessed 22.03.2023.

Metro Vancouver (2022): Metro 2050 Regional Growth Strategy. http://www.metrovancouver.org/services/regional-planning/PlanningPublications/Metro2050.pdf, accessed 22.03.2023.

Ohls, James C.; Weisberg, Richard Chadbourn and White, Michelle J. (1973): The Effect of Zoning on Land Value. In: Journal of Urban Economics 4/1974, 428–444.

Reidsma, Pytrik; König, Hannes; Feng, Shuyi; Bezlepkina, Irina; Nesheim, Ingrid; Bonin, Muriel; Sghaier, Mongi; Purushothaman, Seema; Sieber, Stefan; van Ittersum, Martin K. and Brouwer, Floor (2011): Methods and tools for integrated assessment of land use policies on sustainable development in developing countries. In: Land Use Policy 28 (3): 604–617. DOI: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2010.11.009.

Site Economics Ltd. (2015): The Industrial Land Market and Trade Growth in Metro Vancouver. https://www.portvancouver.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/SiteEconomics-Study_MetroVancouver-Industrial-Land-Market.pdf, accessed 22.03.2023.

UNEP (United Nations Environment Programme) (2011): Towards a green economy. Pathways to sustainable development and poverty eradication. Nairobi: United Nations Environment Programme.

VEC (Vancouver Economic Commission) (2011): The Vancouver Economic Action Strategy: An Economic Development Plan for the City. https://vancouver.ca/files/cov/vancouver-economic-action-strategy.pdf, accessed 22.03.2023.

VEC (Vancouver Economic Commission) (2014): Green Jobs Report. https://vancouvereconomic.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/VEC_GreenJobsReport_2014_web.pdf, accessed 22.03.2023.

VEC (Vancouver Economic Commission) (2017): False Creek Flats Economic Strategy. https://council.vancouver.ca/20170517/documents/cfsc1-AppendixB-FalseCreekFlatsPlan.pdf, accessed 22.03.2023.

VEC (Vancouver Economic Commission) (2018): State of Green Economy. https://vancouvereconomic.com/research/state-of-vancouvers-green-economy-2018/, accessed 22.03.2023.

VEC (Vancouver Economic Commission) (2021): Best Practices for a Just Transition. https://vancouvereconomic.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Best_Practices_for_a_Just_Transition_in_Vancouver_Report_Web.pdf, accessed 29.03.2023.

Webster, Douglas; Cai, Jianming and Muller, Larissa (2014): The New Face of Peri-Urbanization in East Asia: Modern Production Zones, Middle-Class Lifesytles, and Rising Expectations. In: Journal of Urban Affairs 36 (sup1): 315–333. DOI: 10.1111/juaf.12104.