Published 26.04.2023

Planning for Resonant Urban Spaces

Introducing a Theoretical Framework for Studying Making-Practices

Keywords: Resonance; affordance; spatial attachments; making-practices; regeneration

Abstract:

This contribution introduces a theoretical framework that combines Rosa’s theory of resonance with concepts of affordance theory to grasp the relationship between making-practices and the built environment. The framework illustrates how making-practices indicate spatially manifested resonant moments which both assume and alter the affordances of the built environment. This makes these practices particularly relevant to planning professionals and stresses the need to reflect on established planning routines. Referring the framework to (former) urban industrial lands opens up new questions that shall guide the quest to regenerate these urban spaces into reinvigorated sites of production. This contribution ends by outlining the yet undefined zone between offer and appropriation, formality and informality, framing and openness that allows for bottom-up making-practices to emerge; and in its elaboration may assist professionals to plan for more resonant urban spaces.

Situating making-practices

To date, many cityscapes are characterized by short- to longer-term interventions that are built through voluntary actions by citizens. These bottom-up interventions re-assemble public spaces and thereby re-shape the cognitive and bodily experiences of passers-by and users. The practices that make these interventions have the potential to outline alternative urban futures and to recreate the spaces of our everyday lives.

This contribution proposes a framework to study these bottom-up making-practices by focusing on the interdependent relationship between such practices and the built environment. The purposeful engagement with making-practices can generate conclusions for urban planners that help to guide the development of more sustainable and inclusive urban spaces which prioritize the needs of the community. Urban industrial lands, in particular, can serve as a valuable resource for making-practices as they provide an opportunity to repurpose underutilized urban spaces. Reffering the proposed framework to urban industrial lands is ultimately an attempt to make the theoretical learnings more accessible to the planning disciplines and to critically reflect on the stable and structured processes that dominate current planning strategies.

The conceptualization of making-practices set forth in this contribution can be embedded in the larger field of placemaking (see Courage et al. 2021). It can further be related to theories of place attachment (see Manzo and Devine-Wright 2020). Yet, instead of approximating the complex concept of place, the framework presented aims to introduce a relational understanding of making-practices and their situatedness within the built environment. Focusing on the materialistic aspects of urban sites, making-practices will therefore be considered detached from the above-mentioned debates for the time being. Rather, this contribution should be understood as a set of evolving thoughts which map how qualitative moments are experienced within the built environment and connected to making-practices.

In what follows, making-practices are outlined in more depth and connections between making-practices and urban industrial lands are drawn which are illustrated by existing examples throughout the article. Subsequently, Rosa’s theory of resonance and concepts of affordance are introduced and integrated into a single framework for better under-standing making-practices. Based on this framework, potential implications for the planning disciplines are outlined. The contribution concludes with a discussion of how the framework may be applied within the context of regenerating urban industrial lands

Making-practices and urban industrial lands

As a consequence of 19th century industrialization, the physical landscape of many cities still comprises large areas of urban industrial sites that have lost their former functions (Läpple 2016; Nemeth and Langhorst 2014). To date, many of these sites remain under-used or even completely vacant (BBSR 2020, Nemeth and Langhorst 2014). In recent years, the potential for social and ecological transformation that lies in the redevelopment or regeneration of this specific type of inner-city industrial lands has been placed on the agendas of many cities (Nemeth and Langhorst 2014; Loures 2015). These urban spaces are recognized not only as resources to reduce the consumption of raw materials, but also as vast lands that offer room for green spaces, which can enhance environmental protection (BBSR 2020; Loures 2015). Moreover, they are seen as opportunities to reintroduce industries and their economic benefits to the city (Läpple 2016; Loures 2015). Modern manufacturing, such as craft and artisanal local manufacture or technologies of 3D-printing, is particularly suitable to locate in inner-city regions (Läpple 2016; Baker 2017): On the one hand, such productive processes are “relatively clean and quiet” (Baker 2017: 123) and can benefit from consumer proximity (ibid.). On the other hand, they also benefit their surroundings:

“The visibility and presence of industrial activities in the spaces of everyday life can provide rich and distinctive experiences for city dwellers. Stronger connections between productive processes and public space can contribute to a fuller sensory experience of urban life that counters the ‘erosion of the perceptual sphere’ accompanying too much ‘sanitized’ urban re-development.”

(Baker 2017: 122)

While the case for regenerating former urban industrial lands has been made, the question remains: How can these former industrial sites be turned into reinvigorated sites of production? Despite the assets ascribed to the regeneration of industrial land, progress is slow. Literature suggests that this is because municipalities have limited human and financial resources to tackle this highly complex task (BBSR 2020; Loures 2015). Where public or private development has stagnated, bottom-up initiatives and other non-commercial actors can appropriate the lands. They do so with the realization of often low-budget and experimental temporary or interim use projects. The quickly implemented physical changes and the activities that come with these interventions invigorate the unused spaces of former industrial sites, vacant lands and temporarily available spaces by “significantly increasing their visibility and agency within a neighborhood” (Nemeth and Langhorst 2014: 148).

In recent years, such strategies of so-called tactical and temporary urbanism have emerged in many cities (Stevens and Dovey 2022). Especially in urban residential areas, these projects are extremely popular and often catalyze the improvement of the surrounding neighborhoods. They rely on making-practices which, in this contribution, are understood as the act, processes and results of intentional actions that bring about changes to the built environment. The changes are initiated bottom-up and range from small-scale actions, like painting, decorating, seeding and gardening, to rededicating public spaces through temporary parklets, street closures, and pop-up bicycle lanes, and building small to medium-sized structures for urban gardening, workshop spaces and seating areas (Lachmund 2022; Stevens and Dovey 2022; Humphris and Rauws 2021; Krasny 2012). The given examples are a non-exhaustive list and demonstrate the richness of the associated practices. Similarly, the spatial typologies of the built environment vary. Examples include green spaces, residential streets, neighborhood squares, vacant plots and industrial sites.

Examples for making-practices in industrial sites include the initial stages of the projects PLATZprojekt in Hanover, Germany, and the Evergreen Brick Works in Toronto, Canada. In Hanover a group of skaters informally appropriated a property located in an industrial area by the inland harbor and turned the location into a skate park. Originating from these making-practices, the idea of a container village developed. Titled PLATZprojekt, this idea has now been formally implemented on the neighboring property (PLATZprojekt e.V. n. d.). Evergreen Brick Works is the name of a community environmental center run by the non-profit organization Evergreen in Toronto. The center is located in a former industrial site which had been used to manufacture bricks. The brick manufacturer Don Valley Brick Works operated on 9.7 hectares of land for over 100 years (Irvine 2012). Two years after closing their doors in 1984, the land was expropriated by the City of Toronto. In the early 1990s, the then “fledging grassroot initiative” (ibid.: 21) Evergreen started planting trees in one section of the large area. Over the course of twenty years, their small-scale making-practices expanded and professionalized (Evergreen n. d.). Today, Evergreen combines the site’s public spaces and heritage buildings into their public community center.

Practices of making, as they are understood here, have been empirically researched in numerous studies, many of which point to their benefits and challenges (Stevens and Dovey 2022; Dodd 2020). One of these challenges can be traced back to the way in which urban spaces are planned; currently, stable and structured planning processes and products dominate the strategies utilized by urban planning professionals (Vallance and Edwards 2021). This seems to be at odds with the requirements for bottom-up making-practices: These practices point to the need for more “responsive and adaptive policies” when it comes to “creating and managing urban spaces” (Stevens and Dovey 2022).

In order to comprehensively reflect on current planning practices, it has yet to be better understood which elements shape the relationship between making-practices and the built environment. This contribution argues that Rosa’s theory of resonance and Gibson’s theory of affordance (introduced in the following section) can be combined into a single theoretical framework to address these questions. Applying the framework to (former) urban industrial lands ideally allows for conclusions on reflective planning and conceptualizations of spatial components that can foster the regeneration of these sites into reinvigorated sites of production.

Making-practices between resonance and affordance

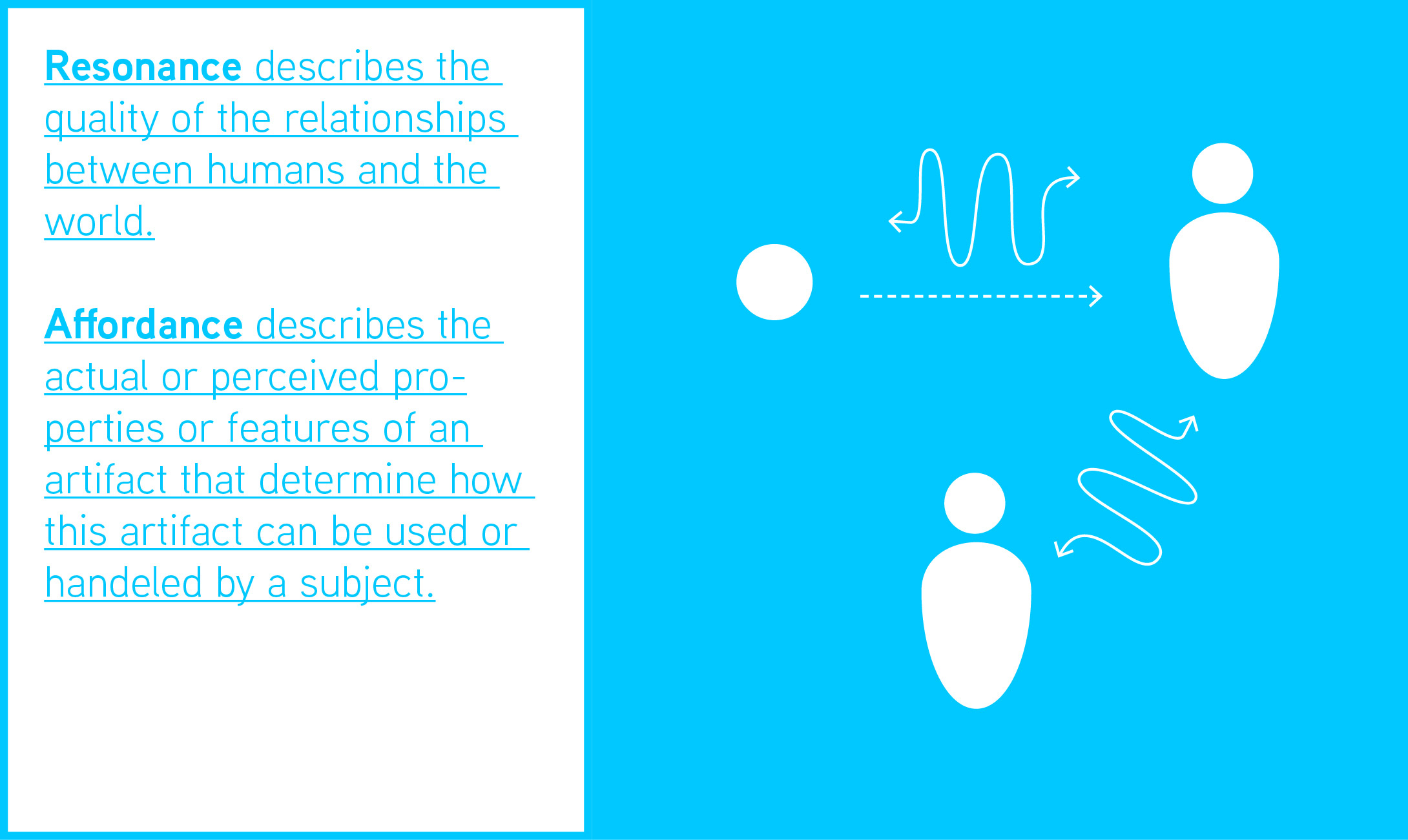

Resonance describes the quality of relationships between humans and the world (Rosa 2016: 13–36). In any particular moment, a subject encounters a fragment of the world. This „world-fragment“ [Weltausschnitt] can, for example, appear in the shape of other subjects, objects, or ideas. If a subject is „affected“ [berührt] by what it encounters, and at the same time also affects the encountered, the connection – or the “wire” [vibrierender Draht] – between the subject and the world begins to vibrate (Rosa 2016: 296). The subject and the world react or respond to each other. This transformative moment, this vibrating wire, is defined as resonance (ibid.).

The term affordance was first introduced by Gibson (1979). Simply put, affordance describes the actual and the perceived features of an artifact that determine how this artifact can be used or handled by a subject (Norman 1988): “A chair affords (‘is for‘) support and, therefore, affords sitting. A chair can also be carried.” (ibid.: 9). As parts of different world-fragments, artifacts and their affordances should be understood in relation to the world.

Rosa’s (2016) theory of resonance does not specify how the built environment relates to resonant experiences. Yet, it has the potential to interlink theories of societies, space, and the social [Gesellschafts-, Raum- und Sozialtheorie]. Relating resonance theory to concepts of affordance theory offers an approach to examining the material configurations and qualities of urban spaces, which are both a basis for and a result of making-practices. This contribution argues that it is possible to address the theoretical gap outlined in the section above by combining the two theories. The following sections can be read as a cookbook; each illustration brings in new ingredients that add up to the complexity of the framework which assumes:

Making-practices are indicators of spatially manifested resonant moments between subjects and the built environment. Resonant moments both assume and alter affordances of the built environment.

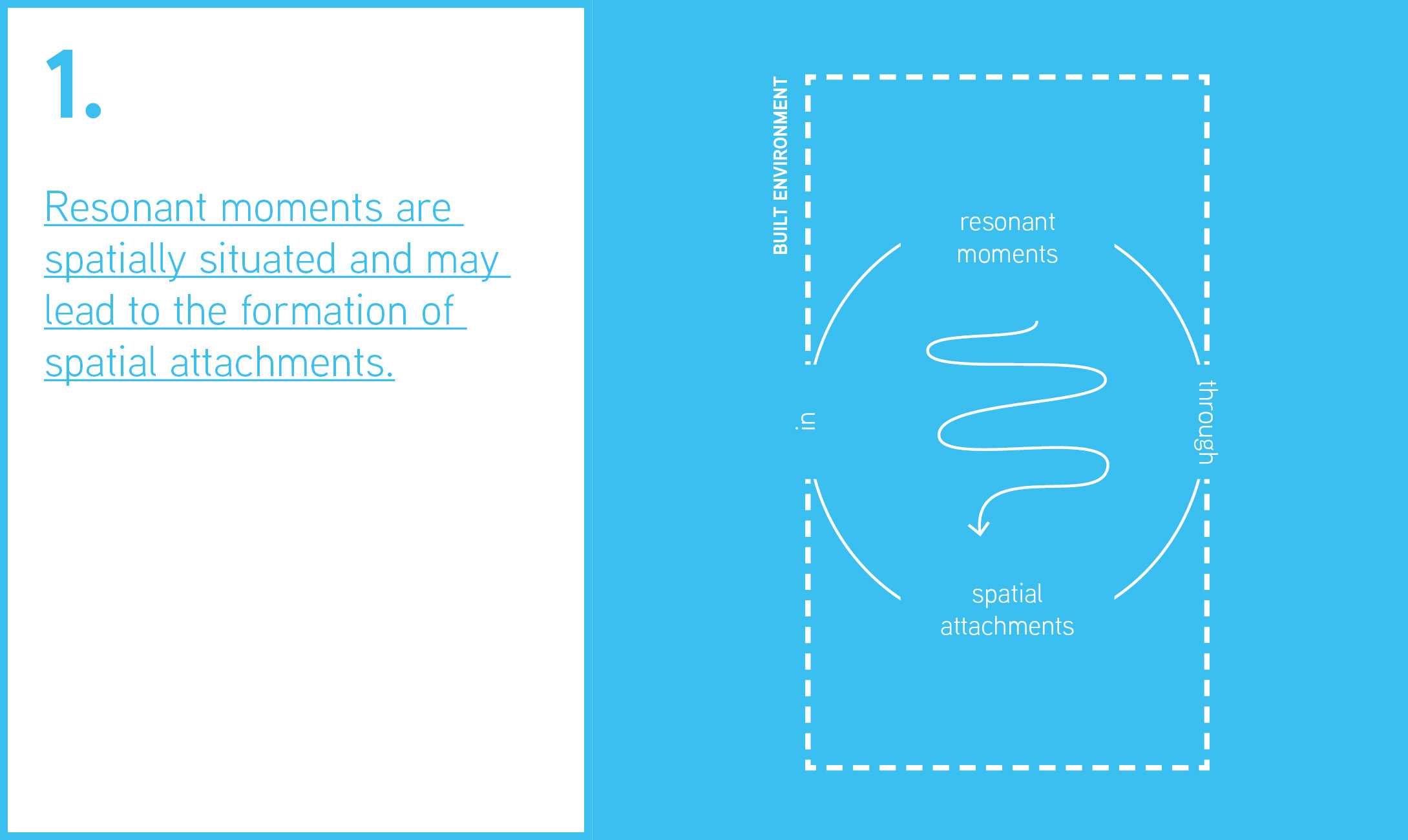

Resonance is a “relational concept” (Rosa 2016: 285) and relations are situated in space. Space is herein conceived as a social phenomenon which comprehends the relationality between people, objects and goods (Löw 2001). Hence, space grasps any material and non-material, as well as human and non-human element that not only constitutes a world-fragment in a given situation, but is also relevant for its coming into being. Within the visualizations of the framework (see Figures 2-6), space is not pointed out explicitly but illustrated as omnipresent (blue background). In contrast, the built environment encompasses every human-made material, structure, and element that ultimately creates the stages, infrastructures, and facilities of our everyday lives. Examples are buildings, pipes, benches, and planted trees which work as single objects or ensembles.

When resonant experiences occur, they imply a transformative moment of affecting and being affected [berühren und berührt werden] (Rosa 2016: 281–298). This moment, key to the concept of resonance, can be understood as an explanation for the reciprocal relationships between subjects and sites: Resonant experiences are internalized by subjects and at the same time, are inscribed into a particular spatial setting. Through this, bonds between subjects and sites form.

The authors suggest to use the term spatial attachments to describe these bonds. The term is similar to that of place attachment, but shall be distinguished from it: Place attachment describes the bond between a subject and a place (Lewicka 2011; Seamon 2013). How meanings are ascribed to places has been studied in various ways (Nelson et al. 2020; Scannell and Gifford 2010; Seamon 2020, 2013; Grenni et al. 2020). Still, insights on the role and agency of materiality in forming these bonds remain rare as the qualities of the built environment play a minor role in current discussions on place attachment (Raymond and Gottwald 2020). In order to address the material dimension of these bonds without disregarding their situatedness in space, the authors employ the term spatial attachments. Moreover, this choice is intended to make clear that the yet evolving framework does not presume to cover the complex and multi-layered concept of place and place attachment. Instead, the relevance of the built environment to such attachments and hence, its relevance to the planning disciplines shall be stressed. The term spatial attachments is employed in plural to indicate the plurality of these very individual, often fluid and contingent bonds between subjects and sites.

However, shifting the focus onto the subject’s embeddedness in the built environment is not a new idea in literature on place attachment. Indeed, taking this perspective indicates that place attachment can form directly and immediately through so-called “perception-action processes” (Raymond et al. 2017), while for a long time it had been assumed that such bonds form slowly and over time. To further expand on this idea, this framework considers the spontaneous formation of bonds between subjects and sites (rather than places) as resonant experiences. By this, research can address the spatial configurations that enable such experiences and better understand how spatial attachments and resonant moments emerge and manifest in and through the engagement with the built environment.

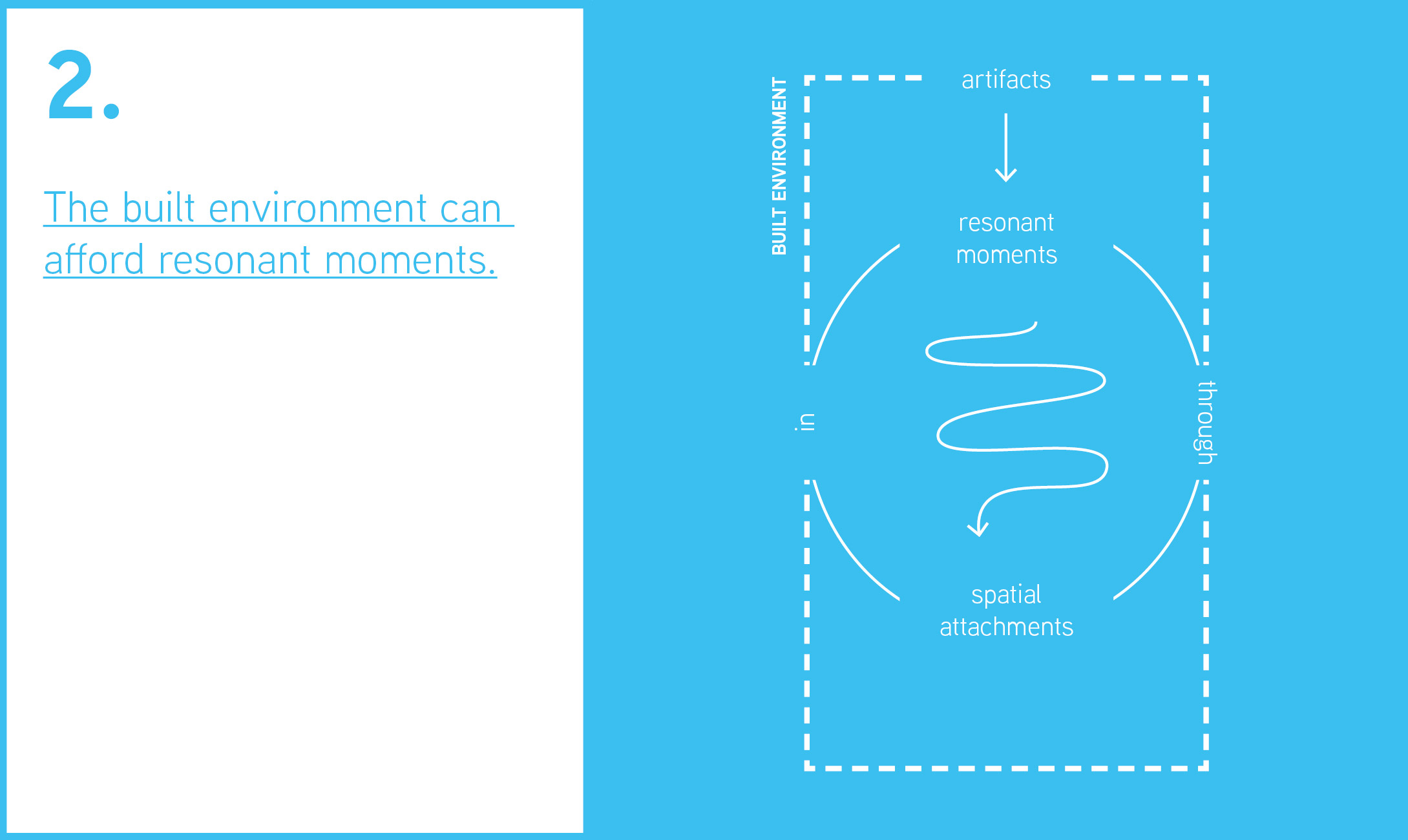

The material world, in this framework reduced to the built environment, can be understood as a condition for the emergence of resonant experiences (Rosa 2016: 633–644). Yet, as mentioned above, Rosa (2016: 381–393, 633–644) does not specify through which ways physical components of the built environment influence resonant experiences. Therefore, drawing on the concepts of affordance may help to explain why some urban sites resonate with subjects, enabling the formation of spatial attachments, and why others do not.

Affordances mediate between the features of an artifact and the actions of subjects (Kaaronen 2017). It has been established that artifacts can request, demand, encourage, discourage, refuse, or allow for certain (re)actions:

“Requests and demands refer to bids that the artifact places upon the subject. Encouragement, discouragement, and refusal refer to how the artifact responds to a subject’s desired actions. Allow pertains to both bids placed upon the subject and bids placed upon the artifact. These mechanisms are neither rigid nor exhaustive, but rather serve as analytic pegs that transpose structure onto subject-artifact relationships, which are at once nebulous and identifiably patterned. Indeed, features can rest ambiguously between categories and slip from one category to another. The mechanisms are thus reference points along a gradated continuum.”

(Davis and Chouinard 2016: 242)

Employing these mechanisms for resonance theory, proposes that artifacts of the built environment can afford resonant experiences in the same manner. However, resonant experiences never function as commands and can therefore neither be requested, demanded, nor refused (Rosa 2016: 299–316). Consequently, the built environment can enable, encourage, or discourage resonant experiences.

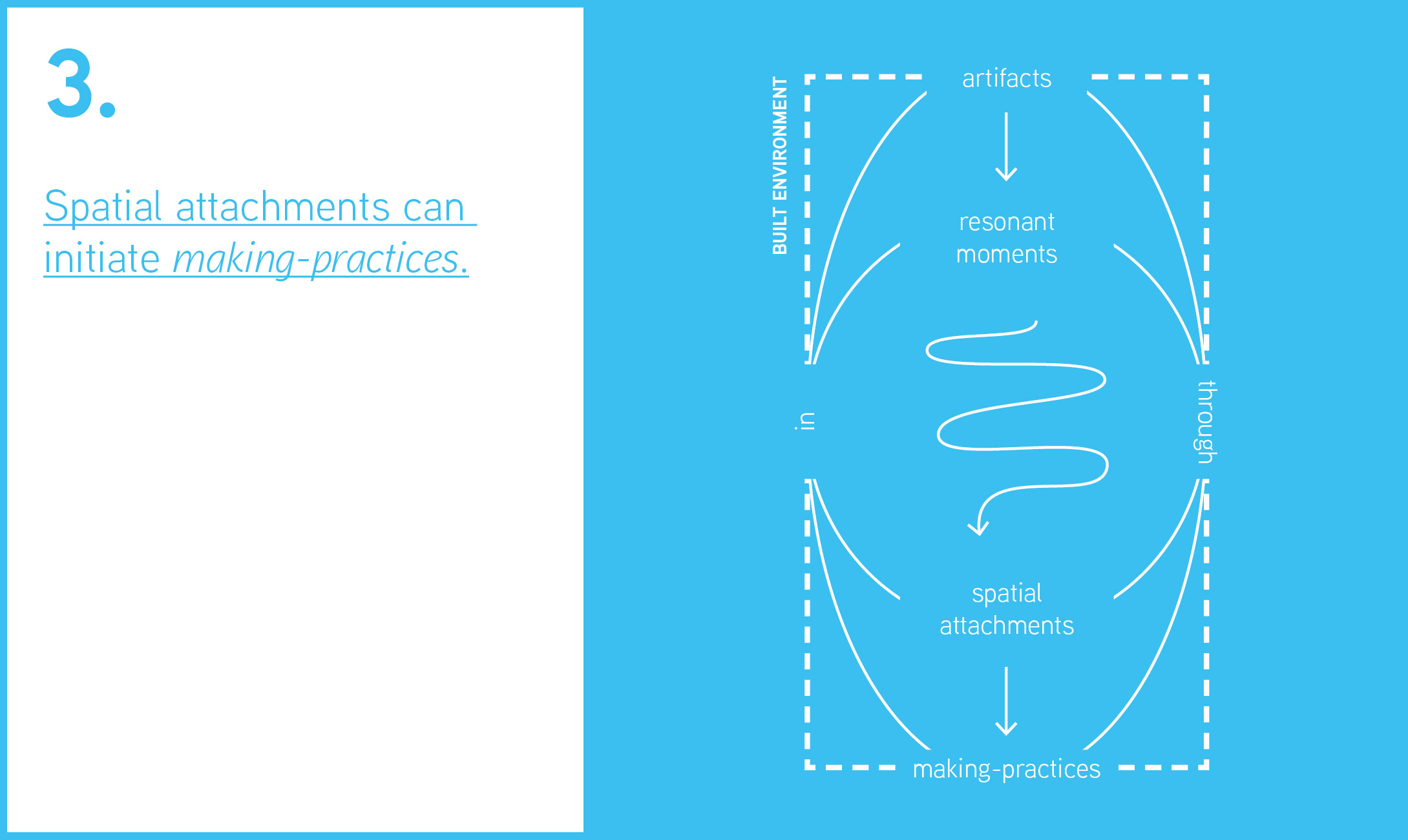

The theory of resonance assumes that all types of civic engagement are founded in a subject’s pursuit of resonant experiences and their self-efficacy (Rosa 2016: 269–281). Making-practices, as described here, are a form of civic engagement. As such, they result from the premise that subjects not only pursue, but also believe that they can experience resonant moments (ibid.: 316–328). Since spatial attachments can be initiated by resonant experiences, they confirm a subject’s self-efficacy in creating these qualitative moments and in turn, further encourage subjects to engage in making-practices. Consequently, it can be argued that through this process, resonant experiences are enhanced and spatially manifested.

Making-practices and the built environment’s capacities to afford (re)produce each other in and through their spatial situatedness in the same way that resonant moments and spatial attachments do. Through making-practices, subjects inscribe themselves into what they make, which is the built environment. At the same time, the made – the built result – is internalized by the subjects that make (Rosa 2016: 269–281) through the experience of making. Hence, subjects and the built environment mutually transform each other through shared resonant moments. Thereby, making-practices change the perceived affordances of the built environment which affects what the built environment offers and means to subjects.

This framework is built to draw conclusions on the material dimension of urban spaces, and more particularly on the built environment. As was established, space – as a condition and context of the built environment – is socially produced (Lefebvre 1974; Löw 2001).

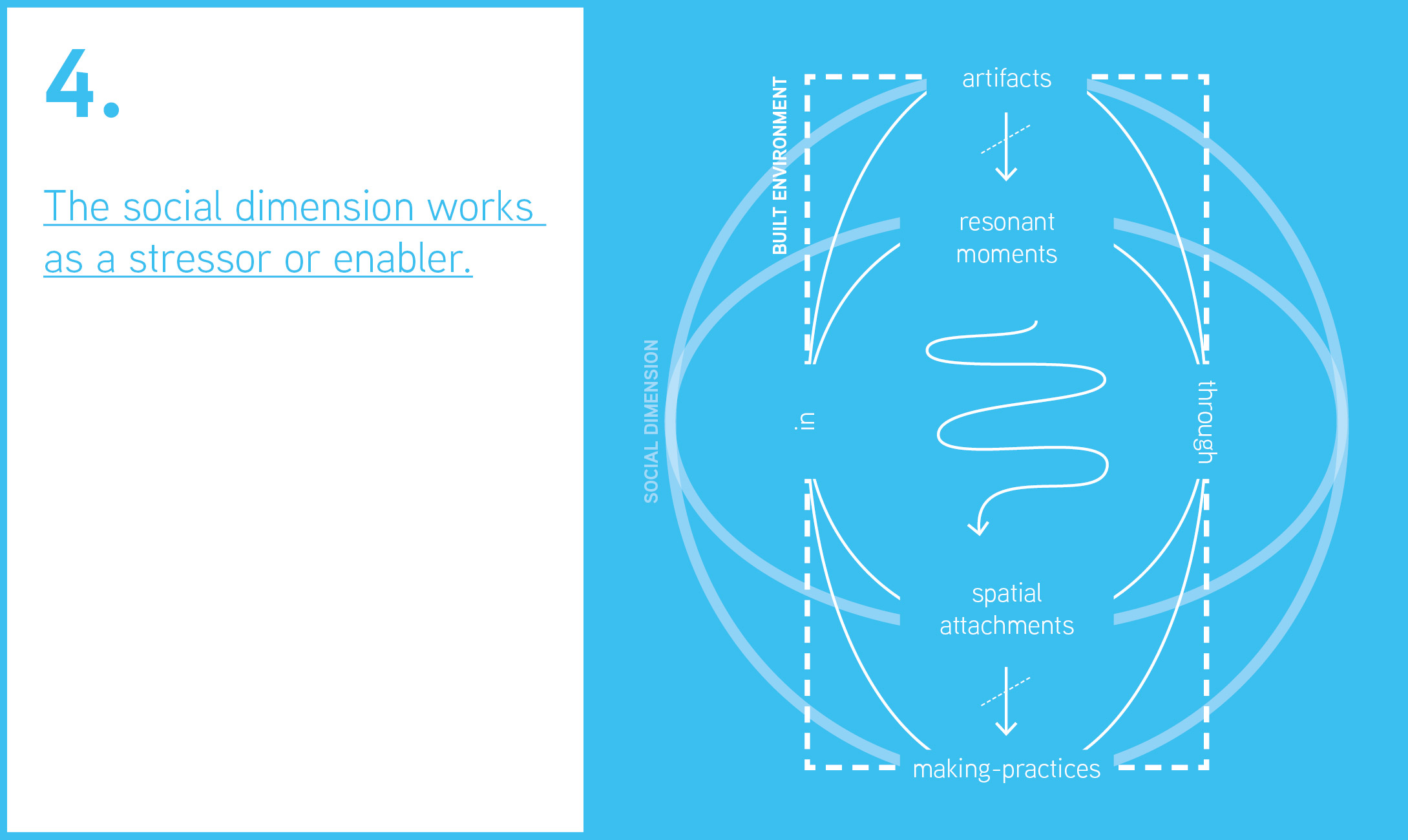

Therefore, this framework must acknowledge the social dimension as a factor, including individual or societal norms as well as cultural backgrounds, values, conditions, and capacities. The social critically shapes how artifacts, and also making-practices, are institutionalized, perceived and acted upon. Thus, subjects and society can enable, encourage, discourage, and, unlike artifacts, even refuse resonant experiences, and thus work as a stressor or enhancer of resonant moments and spatial attachments.

The process illustrated by the framework focuses on individual experiences. Adding the social dimension to this consideration automatically adds a collectivity to the experiences. At this point, it must be noted that the described steps assume a positive relationship between the built environment and making-practices. At any given time, there exists the chance that this relationship remains mute [stumme Weltbeziehung] (Rosa 2016: 276). The possibility that experiences between subjects and world-fragments remain mute (indicated by the dotted lines in Figure 5) can also offer an opportunity for research: Comparing sites with none or hardly any making-practices to those with some, may help to draw conclusions on spatial hindrances for making-practices.

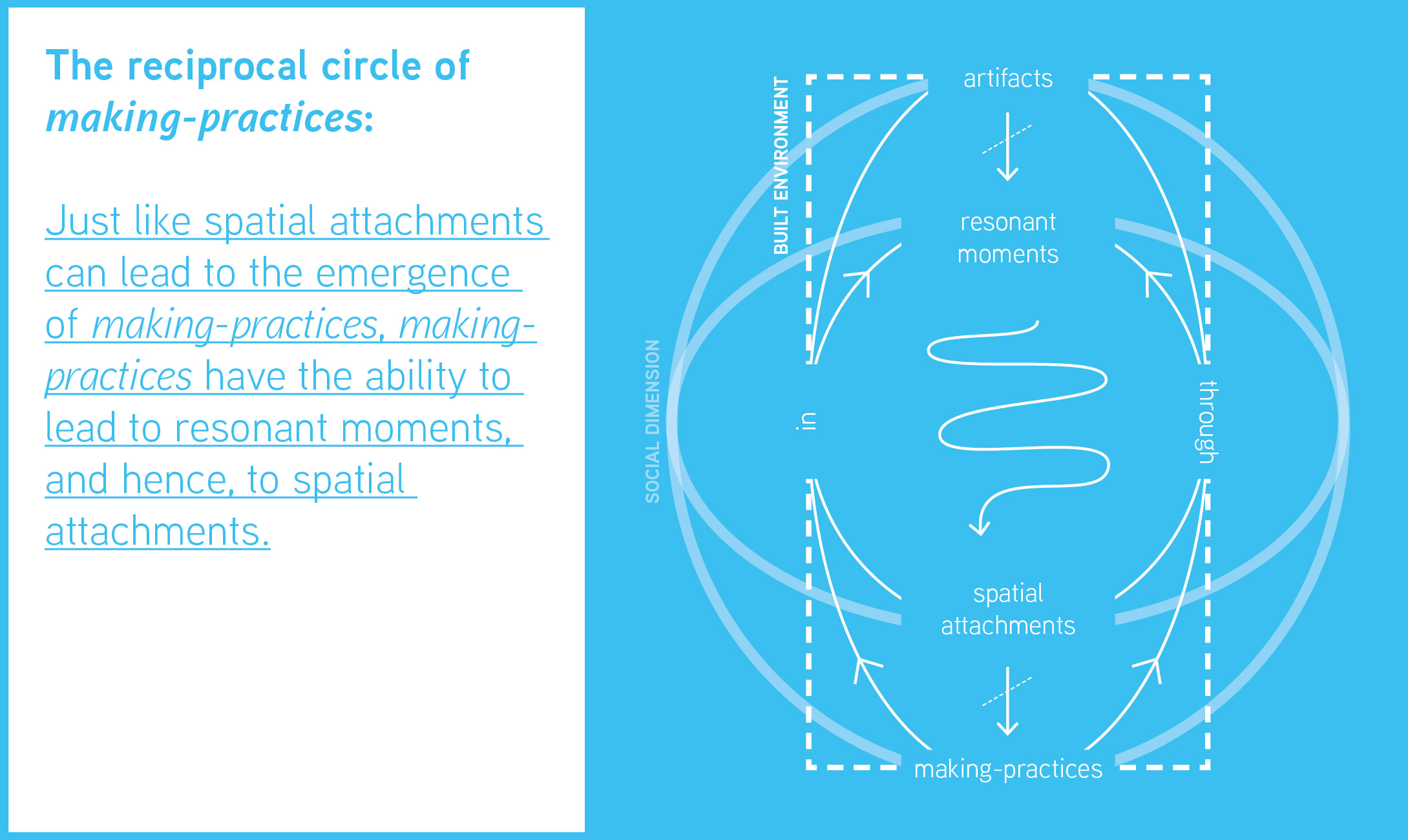

The framework points to two active instances in which spatial attachments can form. In one moment, a subject encounters the world and thereby something changes inside the subject (Rosa 2016: 281–298); in other words, a subject experiences resonance. When resonant moments form spatial attachments (see Figure 2), a consecutive moment can be triggered: Subjects decide not only to experience the space, but to make it (see Figure 4).

Yet, it must be emphasized that making-practices do not result from spatial attachments only. On the contrary, they can also be a response to a growing discontent with urban spaces and (a lack of) policies that address them. Beyond this, just like resonant moments can lead to the emergence of making-practices (see Figure 4), making-practices have the ability to lead to resonant moments, and hence, to spatial attachments. The reciprocal relationship between making-practices and resonant moments highlights the processual and often contingent formation of spatial attachments. This insight coincides with a critique of Rosa’s work: The theory indeed neglects that the constitution of world relations is situated and contingent (Susen 2020)¸ meaning that “meaningful actions are always spatially and temporally located (i. e. situated)” (Raymond et al. 2017: 7).

Planning with and for making-practices

The built environment reproduces social exclusion and inequality (Low 2014). This stresses the need for planners to consider the impacts of the built environment on making-practices as well as the possibilities it can create for them, and vice versa. It has to be understood how the built environment constitutes urban spaces, how it is perceived, which actions it evokes, and which variables influence these perceptions and actions. Gaining a better theoretical understanding of the elements that shape the relationship between making-practices and the built environment can offer a foundation for empirical studies. In their extension, the results can be made accessible to the planning disciplines for the creation of more inclusive, just and diverse urban sites and planning procedures. To make a start, the following part of this contribution highlights several variables and indicates implications of the presented framework for the planning disciplines.

Resources can be considered a decisive factor influencing where, to what extent and how making-practices are implemented. Simply put, resources such as time and money decide over who can and who cannot participate in making-practices. Work (including paid work, care work) can prevent some people from having the time to invest into making-practices. Money can influence how much time an individual has available (for example by having to work less paid jobs or by paying others to do care work for them). Money and time further play a role when it comes to investing into or assembling material resources that can be used to change the built environment. In the same way, time and money available to an individual or a collective shape the extent and the concrete practices of making.

Beyond this, making-practices can even enhance gentrification (Misselwitz 2018) while sustaining precarity. This can be illustrated by the case of Berlin Ostkreuz, an area shaped by high-priced housing investments, large-scale infrastructure projects, and alternative urban practices (Gribat et al. 2015). These alternative urban practices have emerged from failed or delayed development plans over the past 30 years (ibid.). As the case study shows, they ultimately contribute to upgrading derelict land or unused buildings. While the aesthetic and design aspects of these alternative practices are presented, their insecurities and instabilities, including self-exploitation and precarity, are rarely addressed (ibid.).

The observation that making-practices can contribute to valorising urban spaces has led to their instrumentalization for profit-oriented schemes (Misselwitz 2018). With pressure increasing on urban areas, authorities do not just allow for, but even promote making-practices. However, they are often instrumentalized as neoliberal tools and implemented as creative means to urban development and valorization (Bragaglia and Caruso 2022; Misselwitz 2018; Mould 2014; Spataro 2016). This again implies that those initiatives that fit into the schemes are prioritized (for example by tolerating, formally granting, or even funding them) over those that are not as profitable (Misselwitz 2018). The valorisation can initiate or enhance gentrification, which eventually leads to the displacement of established neighborhoods, and with them making-practices. When making-practices are pushed into precarity or entirely displaced the benefits associated with them decrease drastically. Therefore, the planning disciplines still have to grasp the potentials and dynamics associated with making-practices and find ways through which to spatially implement such dynamics in the long run.

Addressing these tensions, the appropriation and making of urban spaces should be paramount to the planning disciplines (Gribat et al. 2015). This implies that urban planners not only need to design spaces which are accessible and open to appropriation, but also have to consider and ideally offer a built environment that reduces or includes some of the resources needed for making. Existing research further points to the relevance of cultural diversity when it comes to perceiving, appropriating, and making urban spaces (Aelbrecht et al. 2022; Kost and Petrow 2022). Regulations and planning strategies can be implemented to secure that making-practices of diverse actors can persist in the future (Gribat et al. 2015). The formality associated with such regulations and approaches needs to allow for the informality that characterizes making-practices. Yet, established strategic planning and making-practices “operate at different scales, assume almost opposite levels of control, and they favor very distinctively different implementation pathways” (Vallance and Edwards 2021: 711). As was pointed out, stable and structured planning processes and products dominate the strategies of urban planning professionals (ibid.). The often impermeable framing in which the planning disciplines are embedded needs adaptation to cater to the openness and flexibility required of both planning policies and urban spaces to enable and support making-practices.

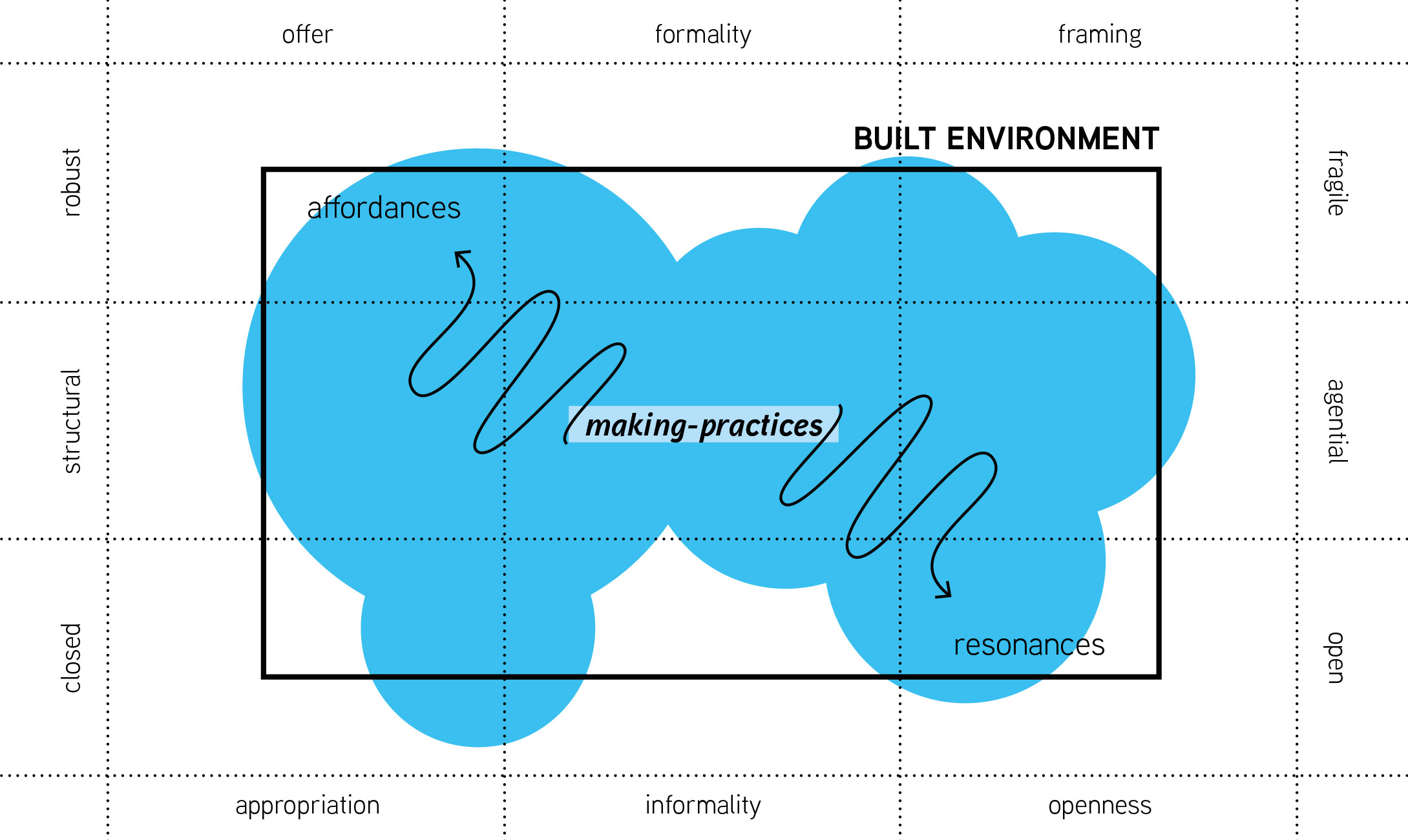

The approaches, which are schematically sketched out in Figure 7, are derived from the previously described tensions found in planning (horizontal axis). They ought to outline the yet undefined zone between offer and appropriation, formality and informality, framing and openness, which potentially enables making-practices.

Based on psychological and phenomenological studies, Rosa (2016: 633–644) argues that architectural design and the arrangements of people and furniture, the material and figurative spatial environment, crucially influence the likelihood of how resonant moments could emerge. In his opinion, “a critique of relations of resonance, both on a large scale (for example with a view to landscape and city architecture) and on a small scale (for example the organization of a sitting area) can and should begin here” (Rosa 2019; translated from the original, Rosa 2016: 642).

Following Rosa’s call, the implications outlined above address the planning disciplines on the large scale, while the framework considers individuals and shall be applied to studying making-practices and their environments on a micro-level. Therefore, the tensions that arise between strategic planning and making-practices will be complemented by tensions that shape resonant moments (Susen 2020: 311):

“(a) They [relations of resonance] are robust because they represent an immanent force of human life. They are fragile because they can be undermined by co-existential conditions that hinder their development.

(Susen 2020: 311)

(b) They are structural because they are embedded in grammars of social interaction. They are agential because they depend on people’s capacity to interact with the world by relating to, working upon, and attributing meaning to the objective, normative, and subjective dimensions of their existence.

(c) They are closed because they have to be sufficiently consolidated to enable those immersed in them ‘to speak with their own voice’. They are open because they have to be sufficiently adaptable to permit those experiencing them to be ‘affected and reached’ by them.”

Making-practices can be used as a lens through which resonant qualities of urban spaces can be studied. The presented tensions should be considered when researching and describing these qualities. Moreover, the proposed categories can help researchers and planners describe, anticipate and plan for making-practices.

However, it must be noted that unknown or unintended purposes or meanings, which may be attributed to the built environment by subjects, can hardly be planned for. Even so, these “accidental affordances” (Furman 2017: 608) can be particularly valuable to the ways in which urban spaces are used and appropriated (ibid.).

Start making!

Facing multiple crises, cities need to become more socially equitable, more environmentally sustainable and more productive (BBSR 2021; Bathen et al. 2019). Many urban spaces hold large potentials for this redevelopment. To unlock this potential, guiding principles have to be rethought (Barrett et al. 2021) and established planning approaches as well as instruments need to be adjusted (BSBK 2018; Dempsey and Burton 2012).

Events like the European Placemaking Week and the growing academic debate around placemaking, its benefits (Hes et al. 2019; Ellery and Ellery 2019), and also its use as a neoliberal or exploitative tool of urban development (Carriere and Schalliol 2021) indicates an increasing interest in placemaking practices and their relevance. This culminates in the call for “richer forms of dialogue through place” and the implementation of active but arguably “messy” responses of citizens (Vitiello and Willcocks 2020), which this contribution has addressed as making-practices. Accordingly, studying and reflecting on these practices, their (spatial) requirements and conditions are of particular significance. Research should ask:

- How can processes of making-practices be catalyzed and integrated into professional planning?

- Which resources are needed to enable diverse and just making-practices in the first place?

The framework introduced in this contribution grasps both the relevance that making-practices have for planning professionals and the need to reflect on currently dominating planning routines. Learning from these practices may guide professionals to plan for urban spaces that better foster resonant moments. As is argued in this framework, resonant moments can spatially manifest. These transformative moments can be afforded by the built environment. The latter can directly be influenced by planners, who can and should further consider the resources that are provided in urban spaces and that enable people from different social and economic backgrounds to appropriate – and possibly make – urban spaces.

The framework is intended for researching making-practices of individuals and groups found in any urban space. This contribution, however, focuses on the framework’s relevance to the subset of urban industrial lands previously outlined. In the beginning of this contribution the question, How can these former industrial sites be turned into reinvigorated sites of production? was raised. As with any question in the realm of urban planning, the answer is complex and differs from case to case. Regardless, this contribution approximates the question of reinvigoration through the lens of making-practices: One way to reinvigorate former industrial sites and turn them into lively sites of production is for planners to not only enable, but also to sustain and value making-practices. This requires studying these practices and their relationship to the built environment in existing cases.

On the one hand, conclusions from studying making-practices in any urban spatial typology can, to some extent, be transferable to the regeneration of urban industrial lands. Such conclusions could include insights on the timely development of a neighborhood and community, and on the resources needed to support making-practices of diverse actors. On the other hand, former industrial sites have very unique spatial qualities that are not always easily adapted to new uses or may even hinder regeneration. It is precisely these qualities that should draw attention to making-practices: Creative and alternative approaches to dealing with the robust materialities and complex building structures of former urban industrial lands can originate from making-practices. At the same time, such structures as well as private ownership over some industrial sites make them less accessible and less visible to the public. This is why extra-effort is required to enable making-practices in these locations.

Reintroducing industries, such as modern manufacturing, to (until then) former industrial sites re-makes them into sites of production. Manufacturing thereby certainly can also be considered as a practice of making, which has parallels to making-practices as they are conceptualized here: Through making-practices the subject is inscribed into the built environment and the built environment is inscribed into the subject. Similarly, a subject who makes a product is inscribed into the product and vice versa.

Cases that combine making-practices and manufacturing activities in inner-city industrial lands offer ideal conditions to do research on how former industrial lands can be turned into reinvigorated sites of production. An example of such sites is the #Rosenwerk, a 0.7 hectares-large urban industrial complex in Dresden Mitte: Amongst other productive institutions and actors, the complex houses a non-profit organization called Konglomerat e. V., a collective of various institutions and makers, who runs a community workshop and promotes practices of sustainable development and self-efficacy (Bathen et al. 2019: 100–101). The collective offers support to artisanal and social projects. For a small contribution, users can work in the workshop’s work areas, which include laser and CNC cutting, 3D-, digital, and screen printing, photography and film, electronics, wood, textiles, and plastic processing, as well as a materials agency (Konglomerat e.V. n. d.). By opening the doors of the workshop to the public and creating a public space, the collective not only makes products, but also ultimately makes their environment.

This contribution concludes with a call for researchers and planners to think about and approach urban spaces more openly. Making-practices can and should thereby be seen as valuable strategies for urban future-making and should thus become an integral part to professional plannings. Research should now address which of the theoretical considerations, anticipated tensions and variables presented in this contribution are of particular relevance to planning for and with making-practices, and as such for creating resonant urban spaces.

The authors of this contribution share co-first authorship.

Funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) - GRK2725 - Project number 445103843

References

Aelbrecht, Patricia, Stevens, Quentin and Kumar, Sanjeev (2022): European Public Space Projects with Social Cohesion in Mind: Symbolic, Programmatic and Minimalist Approaches. In: European Planning Studies, 30 (6), 1093–1123.

Baker, Karl (2017): Conspicuous Production: Valuing the Visibility of Industry in Urban Re- Industrialisation. In: Nawratek, Krzysztof (Ed.): Urban Re-Industrialization. punctum books, 117–126.

Barrett, Brendan F. D., Horne, Ralph and Fien, John (2021): Ethical Cities. London: Routledge.

Bathen, Annette, Bunse, Jan, Gärtner, Stefan, Meyer, Kerstin, Lindner, Alexandra, Schambelon, Sophia, Schonlau, Marcel and Westhoff, Sarah (2019): Handbook on Urban Production: Potentials, Pathways, Measures. Bochum: Urbane Produktion Ruhr.

BBSR (Bundesinstitut für Bau-, Stadt- und Raumforschung) (2020): Nachhaltige Weiterentwicklung von Gewerbegebieten. Ergebnisbericht zum ExWoSt Forschungsfeld. Bonn: Bundesamt für Bauwesen und Raumordnung.

BBSR (Bundesinstitut für Bau-, Stadt und Raumforschung) (2021): Neue Leipzig-Charta. Die transformative Kraft der Städte für das Gemeinwohl. Bonn: Bundesamt für Bauwesen und Raumordnung.

Bragaglia, Francesca and Caruso, Nadia (2022): Temporary Uses: A New Form of Inclusive Urban Regeneration or a Tool for Neoliberal Policy? In: Urban Research & Practice 15 (2), 194–214.

BSBK (Bundesstiftung Baukultur) (2018): Baukultur Bericht 2018/ 19. Erbe – Bestand – Zukunft. Berlin: Medialis.

Carriere, Michael H. and Schalliol, David (2021): The City Creative: The Rise of Urban Placemaking in Contemporary America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Courage, Cara, Borrup, Tom, Jackson, Maria Rosario, Legge, Kyli, McKeown, Anita, Platt, Louise and Schupbach, Jason (Eds.) (2021): The Routledge Handbook of Placemaking. Abingdon/ New York: Routledge.

Davis, Jenny L. and Chouinard, James B. (2016): Theorizing Affordances: From Request to Refuse. In: Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society 36 (4), 241–248.

Dempsey, Nicola and Burton, Mel (2012): Defining Place-Keeping: The Long-Term Management of Public Spaces. In: Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 11 (1), 11–20.

Dodd, Meanie (2020): Space is Always Political. In: Dodd, Melanie (Ed.): Spatial Practices: Modes of Action and Engagement with the City. London: Routledge, Chapter 1.

Ellery, Peter J. and Ellery, Jane (2019): Strengthening Community Sense of Place through Placemaking. In: Urban Planning 4 (2), 237—248

Evergreen (n.d.): Evergreen Brick Works. What is the Evergreen Brick Works: History. https:// www.evergreen.ca/evergreen-brick-works/what-is-evergreen-brick-works/history/, Accessed 15.02.2023.

Furman, Andrew (2017): Exploring Affordances of the Street. In: International Journal for Sustainability and Planning 12 (3), 606–614.

Gibson, James J. (1979): The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

Grenni, Sara, Soini, Katriina and Horlings, Lumminia G. (2020): The Inner Dimension of Sustainability Transformation: How Sense of Place and Values Can Support Sustainable Place-Shaping. In: Sustainability Science 15, 411–422.

Gribat, Nina, Langguth, Hannes and Schulze, Mario (2015): ‚Make-Shift-Urbanismus‘ in den Zeiten einer ‚Absoluten Gegenwart‘? Auf den Spuren städtischer Praktiken um das Ostkreuz in Berlin. In: sub\urban. zeitschrift für kritische stadtforschung. 3/ 2015 (3), 11–124.

Hes, Dominique, Mateo-Babiano, Iderlina and Lee, Gini (2019): Fundamenals of Placemaking for the Built Environment: An Introduction. In: Hes, Dominique, Mateo-Babiano, Iderlina and Lee, Gini (Eds.): Fundamentals of Placemaking for the Built Environment. 1–13.

Humphris, Imogen and Rauws, Ward (2021): Edgelands of practice: Post-industrial Landscapes and the Conditions of Informal Spatial Appropriation. In: Landscape Research 46 (5), 589–604.

Irvine, Seana (2012): Evergreen Brick Works: An Innovation and Sustainability Case Study. In: Technology Innovation Management Review, July 2012, 21–25.

Kaaronen, Roope O. (2017): Affording Sustainability: Adopting a Theory of Affordances as a Guiding Heuristic for Environmental Policy. In: Frontiers in Psychology 2015 (8), Article 1974.

Konglomerat e.V. (n.d): Home - Konglomerat. https://konglomerat.org/, Accessed: 17.02.2023.

Kost, Sabine and Petrow, Constanze A. (2022): Vorwort. In: Kost, Sabine and Petrow, Constanze A. (Eds.): Kulturelle Vielfalt in Freiraum und Landschaft. Wiesbaden: Springer VS, 1–4.

Krasny, Elke (2012): Hands-on Urbanism 1850–2012: Vom Recht auf Grün. In: Krasny, Elke (Ed.): Hands-on Urbanism 1850–2012: Vom Recht auf Grün. Wien: Turia+Kant, 10–37.

Lachmund, Jens (2022): Stewardship Practice and the Performance of Citizenship: Greening Tree-Pits in the Streets of Berlin. In: Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space 40 (6), 1290–1306.

Läpple, Dieter (2016): Produktion zurück in die Stadt. Ein Plädoyer. In: StadtBauwelt 35 (211), 2–29.

Lefebvre, Henri (1974): Die Produktion des Raumes. In: Hauser, S., Kamleithner, C., & Meyer, R. (Eds.). Architekturwissen: Grundlagentexte aus den Kulturwissenschaften. Bd. 2: Zur Logistik des sozialen Raumes (2011). Bielefeld: transcript Verlag, 387–396.

Lewicka, Maria (2011): Place Attachment: How Far Have We Come in the Last 40 Years? In: Journal of Environmental Psychology 31(3), 207–230.

Loures, Luis (2015): Post-Industrial Landscapes as Drivers for Urban Redevelopment: Public versus Expert Perspectives Towards the Benefits and Barriers of the Reuse of Post- Industrial Sites in urban areas. In: Habitat International 45, 72–81.

Low, Setha (2014): Spatializing Culture: An Engaged Anthropological Approach to Space and Place. In: Gieseking, Jen J., Mangold, William, Katz, Cindi, Low, Setha and Saegert, Susan (2014): The People, Place, and Space Reader. London: Routledge, 34–38.

Löw, Martina (2001): Raumsoziologie. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

Manzo, Lynne C. and Devine-Wright, Patrick (Eds.) (2020): Place attachment: Advances in theory, methods and applications. (2nd Edition). London: Routledge.

Misselwitz, Philipp (2018): Rethinking Temporary Use in the Neoliberal City. In: Cupers, Kenny and Miessen, Markus (Eds.): Spaces of Uncertainty. Berlin Revisited. Basel: Birkhäuser Verlag, 60–69.

Mould, Oli (2014): Tactical Urbanism: The New Vernacular of the Creative City. In: Geography Compass, 8 (8), 529–539.

Nelson, Jake, Ahn, Jeong J. and Corley, Elizabeth A. (2020): Sense of Place: Trends from the Literature. In: Journal of Urbanism: International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability, 13 (2), 236–261.

Németh, Jeremy and Langhorst, Joern (2014): Rethinking Urban Transformation: Temporary Uses for Vacant Land. In: Cities 40, 143–150.

Norman, Dondald A. (1988): The Psychology of Everyday Things. New York, NY: Basic Books.

PLATZprojekt e.V. (n.d.): PLATZprojekt INFORMATIONEN. https://platzprojekt.de/infos/, Accessed: 15.02.2023.

Raymond, Christopher M. and Gottwald, Sarah (2020): Beyond the “local”: Methods for examining place attachment across geographic scales. In: Manzo, Lynne C. and Devine-Wright, Patrick (Eds.), Place Attachment: Advances in theory, methods and application. (2nd Edition). London: Routledge, Chapter 9.

Raymond, Christopher M., Kyttä, Marketta and Stedman, Richard (2017): Sense of Place, Fast and Slow: The Potential Contributions of Affordance Theory to Sense of Place. In: Frontiers in Psychology 8, 1–14.

Rosa, Hartmut (2016): Resonanz: Eine Soziologie der Weltbeziehung. Berlin: Suhrkamp.

Rosa, Hartmut (2019): Resonance: A Sociology of our Relationship to the World. [English translation by James C. Wagner]. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Scannell, Leila and Gifford, Robert (2010): Defining Place Attachment: A Tripartite Organizing Framework. In: Journal of Environmental Psychology 30 (1), 1–10.

Seamon, David (2013): Lived Bodies, Place, and Phenomenology: Implications for Human Rights and Environmental Justice. In: Journal of Human Rights and the Environment 4 (2), 143–166.

Seamon, David (2020): Place Attachment and Phenomenology: The Dynamic Complexity of Place. In: Manzo, Lynne C. and Devine-Wright, Patrick (Eds.), Place Attachment: Advances in theory, methods and application (2nd Edition). London: Routledge, Chapter 2.

Spataro, David (2016): Against a De-politicized DIY Urbanism: Food Not Bombs and the Struggle over Public Space. In: Journal of Urbanism: International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability 9 (2), 185–201.

Susen, Simon (2020): The Resonance of Resonance: Critical Theory as a Sociology of World- Relations? In: International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society 33, 309–344.

Stevens, Quentin and Dovey, Kim (2022): Temporary and Tactical Urbanism: (Re)Assembling Urban Space. New York, NY: Routledge.

Vallance, Suzanne and Edwards, Sarah (2021): Charting New Ground: Between Tactical Urbanism and Strategic Spatial Planning. In: Planning Theory & Practice 22 (5), 707–724.

Vitiello, Rosanna and Willcocks, Marcus (2020): How the city speaks to us and how we speak back. In: Courage, Cara, Borrup, Tom, Jackson, Maria Rosario, Legge, Kyli, McKeown, Anita, Platt, Louise and Schupbach, Jason (Eds.) (2021): The Routledge Handbook of Placemaking. Abingdon/New York: Routledge.