Published 26.04.2023

Institutional Innovations in Multi-Stakeholder Redevelopment Projects

A Participatory and Inclusive Approach to Collaborative Development

Keywords: Land management; PILaR; scenario planning; participatory design; social learning; participatory and inclusive land readjustment

Abstract:

The redevelopment of inner urban industrial sites can pose opportunities for upgrading outdated urban areas according to the needs articulated in the Agenda 2030 and the New Urban Agenda. However, reaching these goals with conventional land management strategies is not effective, as they tend to invest insufficiently into climate change mitigation infrastructure and social overhead capital; and support the displacement of weaker households. On top of that they lack the ability to include participatory and inclusive decision-making processes. I argue that these problems are intrinsically linked to the institutional framework employed and the distribution of accountabilities among actors. These shortcomings result in socio-environmental externalities and economic costs. Based on the problems, this contribution discusses an experiment that explores the use of a twostep scenario planning method, that facilitates a process of social learning as a way to employ spatial planning as a tool for positive societal change.

The case for participatory and inclusive planning tools

Since rapid urbanization and climate change are pressing societal issues, international development organizations such as the United Nations or the World Bank have increasingly become interested in public policy precedents that have managed to deal with these challenges successfully (UN Habitat 2016). Current market driven approaches to housing provision and urban redevelopment prove to be ineffective as instruments to supply adequate housing in appropriate locations and concurrently achieve the goals of inclusiveness and sustainability. The market enabler liberalization strategies that have been promoted from the 1980’s onwards (World Bank 1993) have proven to be fruitless as tools for positive societal change. They overly emphasize the role of housing as a financial asset (Rolnik 2019), which promotes the commodification of housing. Due to this emphasis, these policy arrangements tend to produce societal externalities in the form of housing unaffordability, displacement (Durand-Lasserve 2006), an institutional bias that allows market actors to dispossess original residents of the ground rent (Clark 1995), and a lack of investment into social overhead capital and climate change mitigation infrastructure (Floater et al. 2017). These problems are intrinsically linked to the institutional framework employed and the actors’ accountabilities assigned in conventional land management strategies, which result in the aforementioned socio-environmental externalities. However, these institutional arrangements may also have economic implications in cases when the affected residents in an urban regeneration zone join forces and resist a proposed development plan. Organized resistance may hold up development plans and can put pressure on developers. However, delaying development blocks the way for any kind of improvements into basic infrastructure or public facilities to the site that are also beneficial for the residents. Spatial planning has the potential to act as an agent of positive change even in these cases. Only, this requires that governance strategies adopt a different set of land policy instruments, through which socio-environmental planning goals with participatory and inclusive processes could be addressed. Yet, there is too little knowledge about the use of these planning instruments and how they should be employed in practice.

Participatory and inclusive land readjustment

One tool that is explicitly promoted as an institutional enabler at the Habitat III conference and the New Urban Agenda is land readjustment (UN Habitat 2016). Land readjustment is an instrument that rearranges small, scattered landholdings into a more efficient urban structure that is suitable for urban use (Hong und Needham 2007, Doebele 1982). When relating to less invasive planning tools like rezoning, land readjustment has the benefit to be able to completely rearrange property rights within the planning zone. This allows for a more efficient layout of the spatial design and a more effective use of the land values that are created during the intervention. Public agencies can increase the share of land for roads, parks, and add public facilities without the burdensome task of land consolidation or the politically unpopular method of employing eminent domain. When land readjustment is embedding a value capture mechanism, public agencies can divert parts of the land value increment from urbanization for the financing of infrastructure and public services (Alterman 1990). With value capture regulations, all expenses for the development can be financed from the land value increase that derive from public agencies’ actions, such as changes to height, density of land use regulations. It is this aspect that makes land readjustment interesting for cities (in developing as well as maturely developed economies) that must cope with the problem of insufficient resources or fiscal stress.

However, the conventional land readjustment scheme also has limitations. The land value capture scheme for the financing of public goods (Kresse et al. 2020) does not work as a progressive land tool when disputes among different stakeholder groups arise (Shin 2009), and can, depending on the regulatory environment it is being embedded in, become complicit in processes of exclusion and even ground rent dispossession (Kresse and van der Krabben 2022). While land readjustment is regularly discussed as a collaborative land tool, there are limits to its inclusiveness. The common land readjustment scheme does not include residents with weak property rights in the development scheme (Seong-Kyu 1998). This leads to displacement of residents of the lower end of the economic strata and distributes the urbanization gains almost exclusively to the landowners. As a response to this shortcoming, UN Habitat and the Global Land Tool Network (GLTN) has been promoting the use of Participatory and Inclusive Land Readjustment (PILaR). By employing this tool, public agencies promote the participation of all stakeholders in the development process – landowners, tenants, informal residents, professional developers, and community organizations – but also improve the inclusiveness of the land readjustment scheme when ensuring that poor and disadvantaged groups are not being displaced but can influence how the development benefits them personally. While the implementing body only negotiates with the landowners in the common land readjustment scheme and imposes the outcomes of the negotiations on everyone else, all effected stakeholders are included when PILaR is employed (UN Habitat 2016).

There have already been a range of experiments conducted with PILaR. Most of these are located in urban extension zones of cities in developing economies (Cain for Angola 2013, Soliman for Egypt 2017, Delgado & Scheers for Ecuador 2021). But also, the redevelopment of inner urban sites can pose as an opportunity for the use of PILaR.

In particular, this tool could help upgrade outdated urban areas according to the socioenvironmental planning objectives of the New Urban Agenda. This goes for urban renewal locations in developed as well as developing economies.

The potential of PILaR in this context is, however, even less explored so far and no standards concerning the implementation of participatory and inclusive land readjustment processes in practice have been established. This contribution fills this knowledge gap by describing an experimental scenario planning approach for employing the PILaR policy in stalled urban regeneration projects. The method described here embraces the PILaR approach on the one hand and combines it with a social learning methodology that supports the development of collectively shared values and attitudes among stakeholder groups, on the other hand.

Stakeholders’ stalemate blocking positive change

The experiment has been carried out in an urban renewal site called Euljiro in Seoul, Republic of Korea (compare Figure 1), where a series of consecutive redevelopment plans have been made and discarded for several decades. In this context, local urban redevelopment law prohibits changes to the urban structure, including mere building improvements, once a redevelopment plan is announced. As a consequence, no significant developments or even maintenance can be carried out. As a result of this law, the planning zone shows a lack of basic infrastructure (no sanitation in some parts) and safety measures (improvised electricity, large parts inaccessible for fire trucks). The latest urban renewal plan (2019) is being supported by the landowners and the developers but is being opposed predominantly by residents with rental agreements. The community of organically grown small-scale manufacturing industries and artists is resisting the redevelopment of the site into an upscale high-rise development for the upper middle-class. The residents have –after a series of protests and lobbying efforts – managed to gain the support of the local government who started to oppose redevelopment and the associated displacement. Until today no agreement for a development plan could be finalized that satisfies all stakeholders. Consequently, the stalemate among different stakeholder groups has resulted in a deadlock for any development and the site cannot live up to its potential in terms of providing housing, upgrading basic infrastructure, overcoming sub-standard health and safety conditions, sustainably improving built urban structure, implementing additional sustainability measures, and distributing profit to the landowners.

Social learning with scenario planning in PILaR

The experiment with the PILaR method draws on vast experiences with the conventional land readjustment technique within Korea as a point of departure and makes a case for upgrading this tool for today’s challenges. PILaR is better suited to address these challenges than conventional land management strategies because conventional land management strategies are not inclusive and tend to limit the amount of social overhead investments once a certain level of public service provision is satisfied (Weisbrod 1986). While land readjustment in the past has predominantly worked for the landowners and the public, PILaR can provide a higher level of public services of sustainability infrastructure if the stakeholders manage to find common ground.

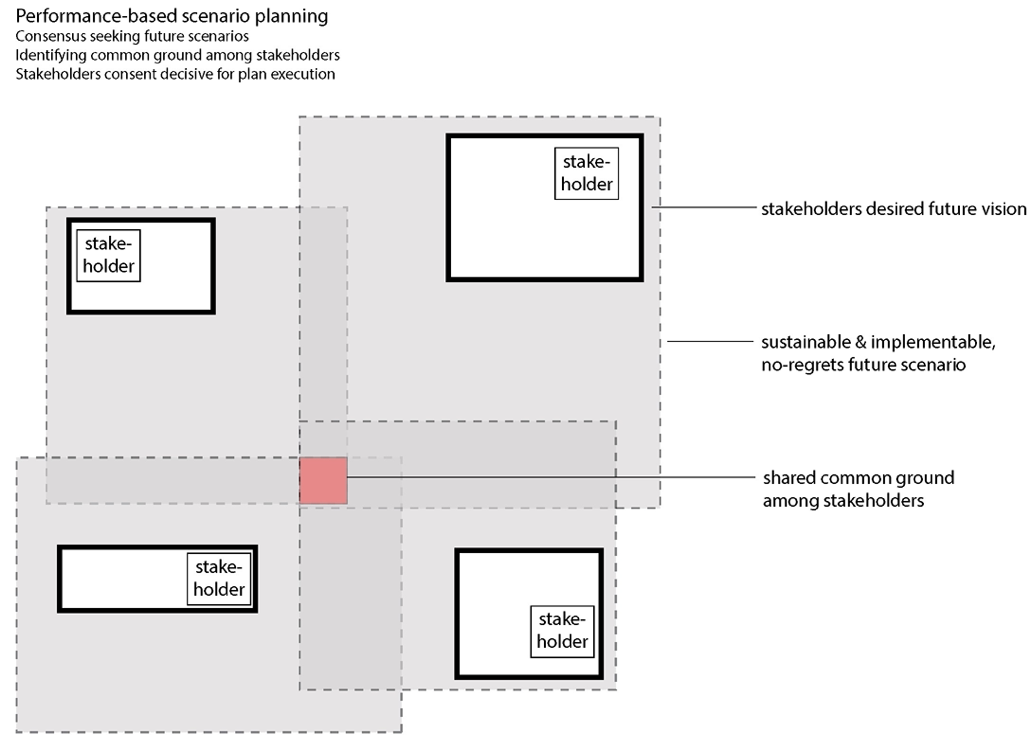

The PILaR method relies on voluntary collaboration among various stakeholders. However, the instrument does not prescribe how this collaboration should be facilitated to be successful. Therefore, the experiment uses Brown’s community-based planning method to fill this methodological vacuum (Brown 2008, Brown und Lambert 2015). Key in these efforts is to engage stakeholders in a dialogue through which opposing parties can learn to understand each other’s positions, develop empathy, and start to establish a local planning culture that develops a commonly shared vision to which all stakeholders commit (Brown und Lambert 2015). This type of social learning involves a two-step scenario planning process in which the local planning culture emerges from a set of commonly shared values and attitudes (Li et al. 2020) (compare Figure 2). Based on these shared values and attitudes, new but common ground for development can be found.

“The collective social learning model recognizes the importance of bringing a diverse mix of individuals together to achieve a whole-of-community transformational change to which the participants have real commitment”

(Brown and Lambert 2015).

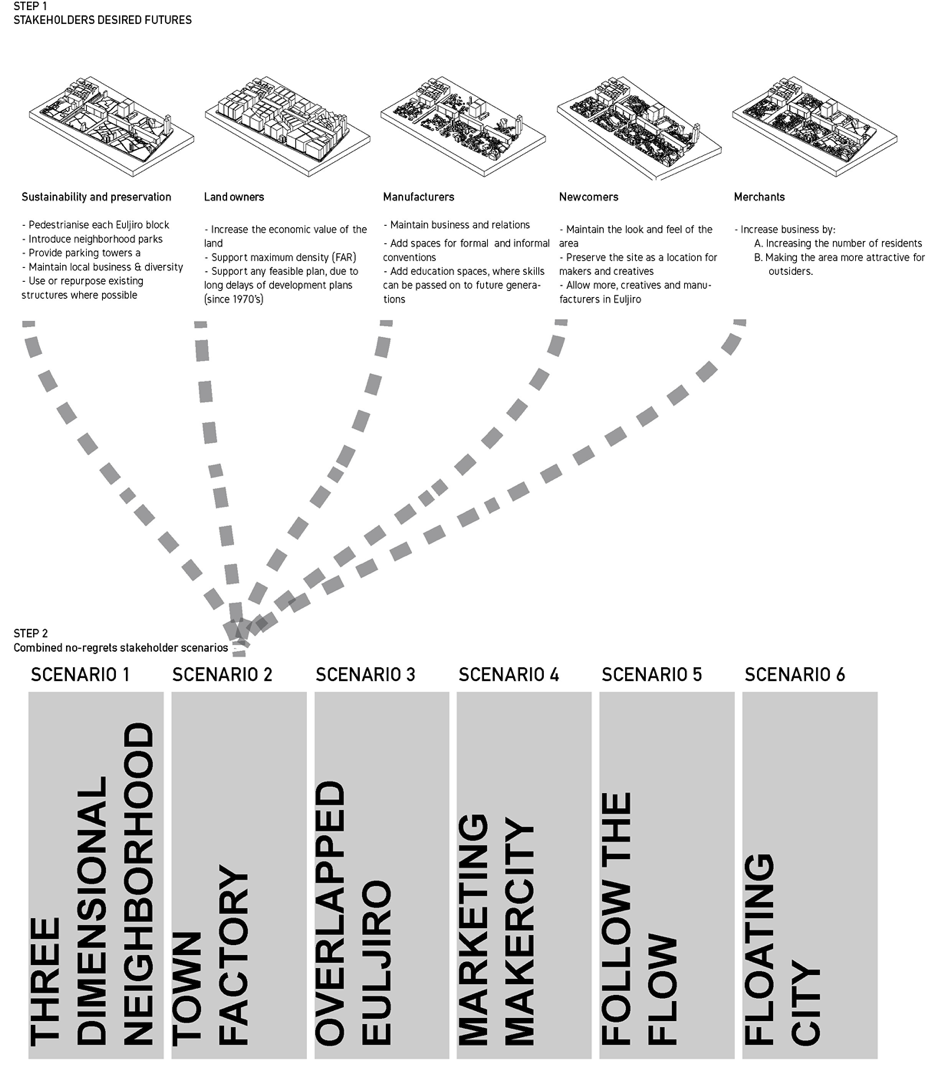

The two-step process works as follows: first, stakeholders’ positions are identified through a survey and a set of interviews with landowners, residents, community leaders, commercial parties, and public officials. This data is translated into so-called Stakeholders Desired Future Scenarios, which resemble the uncompromised best-case outcome for each of the individual stakeholder groups in respective urban mass models. These mass models help to quantify stakeholder visions and open the scheme for discussion and a qualitative assessment (compare Figure 3). As stakeholder groups often lack oversight and technical expertise, it is unlikely that the Desired Future Scenarios comply with the demands of financial feasibility and the integration of climate change mitigation infrastructure. On top of that, individual stakeholder groups’ Desired Future Scenarios tend to lack the collaborative thought that would integrate other stakeholders’ ideals into their own visions. The compartmentalization through diverging values and attitudes describes why the collaboration has failed in the experiment for Euljiro.

In the case of Euljiro, desired future scenarios were clearly divided. Landowners were predominantly occupied with the chance to take advantage of opportunities to develop the land and generate handsome profits. Particularly, the series of consecutive unrealized development plans since the 1970’s that restricted the landowners from capitalizing on their land induced a sense of urgency to not miss out on this rare opportunity. Consequently, this stakeholder group favored building up to the maximum floor area ratio (FAR) allowance. The manufacturers, on the other hand, mainly sought to maintain business networks of longstanding collaborators. On top of that, manufacturers lacked additional spaces for conventions, as well as educational spaces where skills can be passed on to the next generation of manufacturers. The newcomers - predominantly artists - flocked to the site for the low rents and appreciate the current potential for collaborations between creative industries or established manufacturers. On top if that, these stakeholders also show a greater appreciation for the look and feel of the area, which compels this stakeholder group to advocate for the preservation of the status quo in their Desired Future Scenario. Merchants, predominantly from the electronics, printing, restaurant and retail sector are mainly interested in growing their businesses. They are less involved with the manufacturers and the newcomers. Therefore, this stakeholder group favours of the densification and further promotion of Euljiro as a site for leisure and consumption that is attractive for tourists. The last desired future scenario has been developed by professional agencies and shows how the ecological performance of the site can be improved with community amenities such as enlarged neighborhood facilities and open spaces. Additionally, the merchants Desired Future Scenario tackles the parking problem and articulates a preservation strategy for existing local businesses.

In the second step of the process, individual Desired Future Scenarios are re-interpreted and worked out into combined No-Regrets Scenarios. Here, each scenario combines the key aspects of each desired future scenario for the individual stakeholder groups and integrates them with the requirements for sustainable neighborhood development, such as connectivity of the urban fabric, walkable streets, compact and mixed-use developments, availability of public spaces, and access to public transport, among others.

Based on this, the interpretation of the Desired Future Scenario’s leads to a set of proposals for a financially feasible massing and land use distribution. Following Brown’s decision-into-practice learning spiral, the No-Regrets Scenarios work as propositions that illustrate a variety of options through which common ground among different stakeholder groups may be found in a process of collective learning. Here, different stakeholder groups "move together in an interactive, iterative process in which everyone enhances the understanding of everyone else" (Brown 2008). No-Regrets Scenarios form the base for conformance-based planning that centers on an inclusive and participatory discussion of previously established diverging scenarios; this includes all stakeholders. The purpose of the No-Regrets Scenarios is not to present perfect development paths, but to facilitate an understanding of each other’s values and approaches. Based on this, the scenarios facilitate a process of discussion and collective learning through which stakeholders negotiate competing scenarios. Here all stakeholders engage in open discussions and are encouraged to propose amendments to their preferred options. This process supports the growth of mutual understanding and the development of joint values and approaches that can lead to the development of a collectively supported future development scenario.

The two-step process supports a participatory and inclusive application of the PILaR policy. At the same time, this process helps develop a local planning culture that further creates shared planning values. This leads to the development of a collective development vison, which includes the objectives of all residents’ groups, public agencies, and commercial stakeholders through participation. Ultimately the policy helps in overcoming development deadlock, while the introduction of a sustainable Desired Future Scenario in this process allows participants to pave a way for the seamless integration of socio-environmental planning goals according to the New Urban Agenda.

References

Alterman, Rachelle (1990): Private Supply of Public Services: Evaluation of Real State Exactions, Linkage, and Alternative Land Policies. New York University Press.

Brown, Valerie A (2008): Leonardo‘s Vision: A guide to collective thinking and action. Brill.

Brown, Valerie und Lambert, Judith (2015): Transformational Learning: Are We All Playing the Same‘Game‘? In: Journal of Transformative Learning 3 (1): 35–41.

Cain, Allan; Weber, Beat und Festo, MOISES (2013): Participatory inclusive land readjustment in Huambo, Angola.

Clark, E. (1995). The rent gap re-examined. Urban Studies, 32(9), 1489–1503.

Delgado, Alina und Scheers, Joris (2021): Participatory process for land readjustment as a strategy to gain the right to territory: The case of San José–Samborondón–Guayaquil. In: Land Use Policy 100): 105121.

Doebele, William A. (1982): Reshaping Land Readjustment to Serve the Needs of Lower-Income Groups: The 1980 Korean Master Plan. In: Doebele, William A. (ed.): Land Readjustment: A Different Approach to Financing Urbanization. Cambridge: Lexington Books.

Floater, Graham; Dowling, Dan; Chan, Denise; Ulterino, Matthew; Braunstein, Juergen and McMinn, Tim (2017): Financing the Urban Transition: Policymakers‘ Summary. London and Washington, DC: London School of Economics & PwC.

Hong, Yu-Hung und Needham, Barry (2007): Analyzing Land Readjustment: Economics, Law, and Collective Action. Cambridge: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

Kresse, Klaas und van der Krabben, Erwin (2022): Rapid urbanization, land pooling policies & the concentration of wealth. In: Land Use Policy 116): 106050. DOI: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2022.106050.

Kresse, Klaas; Kang, Myounggu; Kim, Sang-Il und van der Krabben, Erwin (2020): Value capture ideals and practice – Development stages and the evolution of value capture policies. In: Cities 106): 102861. DOI: 10.1016/j.cities.2020.102861.

Lee, Suh-yoon (2019): Euljiro‘s last stand: Redevelopment rips through historic manufacturing hub.

Li, Keyang; Dethier, Perrine; Eika, Anders; Samsura, D Ary A; van der Krabben, Erwin; Nordahl, Berit und Halleux, Jean-Marie (2020): Measuring and comparing planning cultures: risk, trust and co-operative attitudes in experimental games. In: European Planning Studies 28 (6): 1118–1138.

Rolnik, Raquel (2019): Urban warfare: Housing under the empire of finance. Verso Books. Durand-Lasserve, Alain (2006): Market-driven evictions and displacements: Implications for the perpetuation of informal settlements in developing cities. In: Informal settlements: A perpetual challenge): 207–230.

Seong-Kyu, Ha (1998). Urban growth and housing development in Korea: a critical overview. KOREA JOURNAL, 39(3), 63–95.

Shin, Hyun Bang (2009): Property-based redevelopment and gentrification: The case of Seoul, South Korea. In: Geoforum 40 (5): 906-917. DOI: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2009.06.009.

Soliman, Ahmed M. (2017): Land readjustment as a mechanism for New Urban Land Expansion in Egypt: experimenting participatory inclusive processes. In: International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development 9 (3): 313-332. DOI: 10.1080/19463138.2017.1382497.

UN Habitat (2016): Remaking the Urban Mosaic—Participatory and Inclusive Land Readjustment.

UN Habitat (2016): Urbanization and Development: Emerging Futures; World Cities Report 2016. In: Nairobi, UN Habitat).

United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat) Nairobi, Kenya.

Weisbrod, Burton A (1986): Toward a theory of the voluntary nonprofit sector in a three-sector economy. In: The economics of nonprofit institutions. Oxford University Press.

World Bank (1993): Housing Enabling Markets to Work: A World Bank Policy Paper. The World Bank.